From the moment I started at the academy I noticed that sculpting was very demanding on both a physical and a psychological level. This has never diminished. I very much like what I do, but a large percentage of my practice involves…..

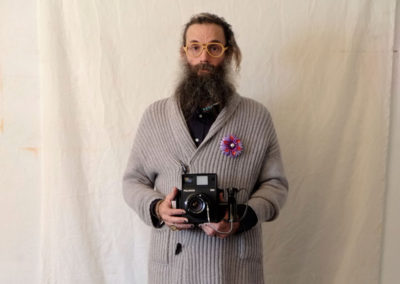

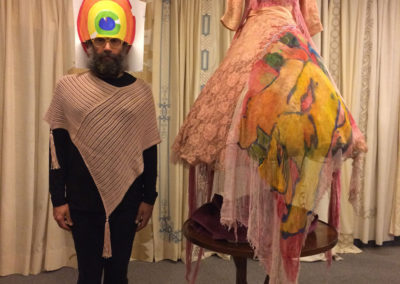

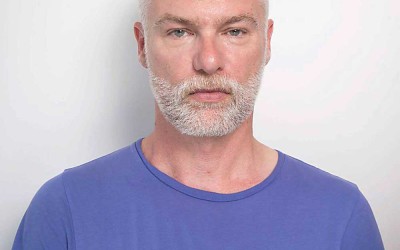

Nadia Naveau

Nadia Naveau

Text JF. Pierets Artwork Nadia Naveau

I’m going to start with a quote by Ai Weiwei: “Being an artist is not a job, it’s an identity”.

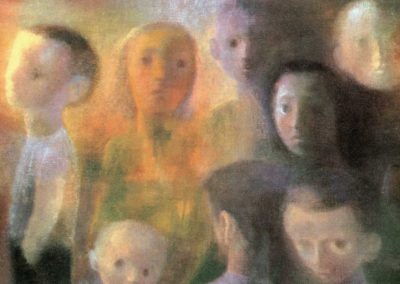

Definitely! From the moment I started at the academy I noticed that sculpting was very demanding on both a physical and a psychological level. This has never diminished. I very much like what I do, but a large percentage of my practice involves – let’s call it ‘suffering’ for lack of a better word. You can’t underestimate the hard work involved in a creative process. Maybe it has something to do with my perfectionism and the way I always seek to surprise myself. I am able to make large and complex series like Salon du Plaisir – but then I have to change everything and make it challenging again. I want to keep finding things that I don’t know yet. I want to keep on being amazed. Those steps can be very small, and they may not even be noticed by the public, but for me they are very important. That’s the thing I’m pursuing. That doesn’t mean it always works out. So when it doesn’t, I’ll feel unhappy and unsatisfied. But when it does you have the feeling that you can literally do anything. It’s a never ending circle which I’m quite familiar with by now, but when I was younger I definitely considered giving up art and starting a day job.

Can you describe what you are looking for?

That’s difficult to explain because in the first place it’s about a certain tension between shapes, between abstract or organically formed elements. I’m also looking for surprise. I’m always curious and never satisfied with things I already know. I keep searching for the new. Although ‘searching’ may be the wrong word because I have the feeling that I bump into things. They’re just there when I need them. When I’m in this creative flow, things come my way. Those things can be very banal. It can be a color, a shape, or even a chip of wood from a chair. Everything automatically makes sense and comes to terms with what I’m working on at the moment. I know it all sounds a bit abstract but it makes sense in my head. I guess you can compare it to a jigsaw puzzle where every piece automatically leads to the big picture.

If you say you want to surprise yourself, does that mean that you never know the outcome?

Not always, no. All the images in my mind translate into the clay as some sort of collage. Sometimes I don’t know where an image comes from, yet when the piece is finished and I start talking about it, spend time with it, it all matches up. It all becomes clear. I notice I keep on fostering connections between what I did before and how I can make it more abstract, or make a different version of it. Every piece is a step forward to the next one. Even little things like collages or pictures I make, are a prelude to the piece that comes next. My intuition is often faster than my interpretation or reason.

What makes you go to your studio every time?

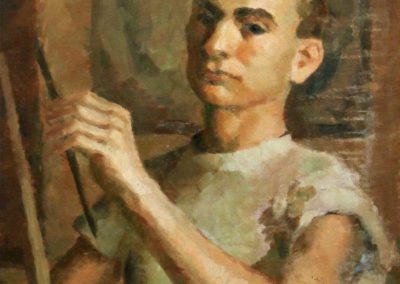

Discipline and action. When I’m – for one reason or another – a bit rusty, I start making things through boredom. Things I know, things that don’t take any effort. I start sculpting Nick (Nadia’s husband, painter Nick Andrews), which gets me going most of the time. It’s all about doing things. I get a lot of inspiration from magazines, from traveling or design, but in the end you just have to start and see where it leads you. However, I’ve also learned that it’s not bad to take a break every now and then. Especially after an exhibition when it’s important to wind down. And even when feelings of guilt start to kick in, I always acknowledge the value of just doing nothing for a while. Sometimes you just have to let go.

Some African languages don’t have a word for artist, but translate it as magician: someone who puts magical powers into an object? What do you put into your work?

I have the feeling that I literally put everything into my work. And since I often cannot recall how I’ve made something, the fear of not being able to do it anymore lingers once in a while. Even when everything always works out fine, I cannot say that the process is obvious. It’s a huge contrast to when I’m feeling confident. The greatest moment is when you feel that everything connects, when you are in the middle of this creative process where all the pieces come together. Then I can even say that I’ve made the best thing I’ve ever seen! This doesn’t mean I’ll have that same feeling the next day, but it’s a good start. It’s an addictive feeling though. The adrenaline you feel when you’re on a confidence high is great. It’s very empowering. Enough to keep me going through the tougher times. Thankfully I’m able to put it more and more into perspective because absolutely no creativity comes from being in a negative loop.

Do you see the world differently as an artist?

Probably. But I have difficulty saying so because to me it sounds very pretentious. But there is indeed a big difference between how I view the world and how, for example, my parents are experiencing it. Maybe that’s what they call ‘a trained eye’? However, being a good artist is not only about how you see the world. It’s not even solely about talent. You also have to be determined. And be disciplined. Without lapsing into a regular pattern. Because then you stop evolving. An art collector once told me that he kept on buying my work because he loved to see how I was evolving. And how he always stops buying pieces from artists who’ve become predictable. That was one of the biggest compliments I’ve ever gotten.

‘I like people to experience what they think and feel for themselves. Art opens people’s minds.’

How important is acknowledgement?

Very. I don’t think I could be the kind of artist that only creates without showing it to an audience. I’m happy to have the possibility to exhibit and enjoy the fact that people are seeing what I’ve done. It’s also very nice that after all this time of solitude, you get to put your work out there. It can be very rewarding.

Is it important that people like your work?

I’m quite sensitive about it but it doesn’t guide me. Otherwise I would still be doing what I did 5 years ago. But I do feel good when people like my work. When I’m in my studio I’m on such a different planet that there’s not a thought in my mind about pleasing my viewers. However, I find showing my work in a gallery pretty stressful. You’ve given it your very best and all of a sudden people have an opinion about what you’ve been doing. It’s very confrontational stepping from your studio into a place where all of a sudden you’ve become someone with the intention of doing business. I think the art world has evolved in such a way that it’s necessary to step fully into the process of both creating and presenting. And since I’m very bad at the business side of things, I’m very happy that I have a gallery that takes care of this.

When did you start calling yourself an artist?

I still don’t. It feels weird. I always say I’m a sculptor. I think that covers it. This is a conversation I often have with my students: it’s the difference between being an artist and artistic practice. I don’t think it’s the same thing. For me, being part of the art world is called artistic practice, which doesn’t necessarily mean that you are an artist. Obviously I want to be part of that world, yet I don’t want to be swayed by it. It’s not what makes you an artist.

I don’t often read about or hear you explain your work. Why not?

I always feel that it doesn’t matter. That it isn’t necessary. I find what people say or write about my work more appealing. Although often surprising, I find someone else’s interpretation very interesting to think about, as opposed to when I talk about it myself. I don’t have the feeling that me talking about it adds any value. Maybe it’s because explaining your work ends the conversation. I like people to experience what they think and feel for themselves. Art opens people’s minds. When I started at the academy I found that it made me wiser, more grounded. And going to a museum often has a very big influence on the way I think. But this is what it does to me personally. When it comes to other people I do hope that my work makes people think, that it has a certain impact on how someone sees the world.

Does art have to be socially relevant?

There are always issues popping up along the way but my first reaction would be to say no. Not necessarily. Someone can view a piece of art as ‘just’ appealing. It’s not easy to say that nowadays, but I do believe that. However, a good work of art mostly contains all those qualities. Depending on the place and time where it’s created. It’s significance can even grow, becoming symbolic over time. For me it’s more important to make a balanced work than to make a point. Beyond the aesthetics, it’s important that the image is accurate. Like a painter who finds his balance with color, or a musician finding the right notes. For me it’s playing with forms and shapes.

How does it feel to live with another artist?

Honestly, I cannot imagine not living with an artist. If you’re together for more than 20 years, like we are, you grow together towards new things. You experience transformation together. Also, I couldn’t do without his feedback. I don’t like to have people in my studio when I am working, but it’s very important that Nick drops in because he instantly feels what I’m doing. Often it’s about the little things, but it’s easy for us to see what can make the other one’s work stronger. And because we know each other’s work through and through, it becomes very intuitive. His influence is never far. And the other way around.

What makes you most happy?

Being with Nick and sculpting. Because that’s what I do best. The former is about love and what we are doing together, how we are exploring other countries and our work. The things we are experiencing and how we turn that into works of art. The latter makes me extremely happy in a very intense manner, but it can equally make me very unhappy. I was raised very strictly, so considering my upbringing it’s not evident that I would have become a sculptor. I had to fight pretty hard to be able to do what I am doing now, so it must be very important. Otherwise I would have given up very easily. It’s both an urgency and an emergency.

Related articles

Nadia Naveau

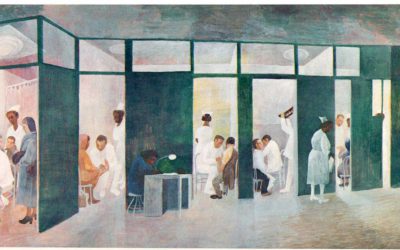

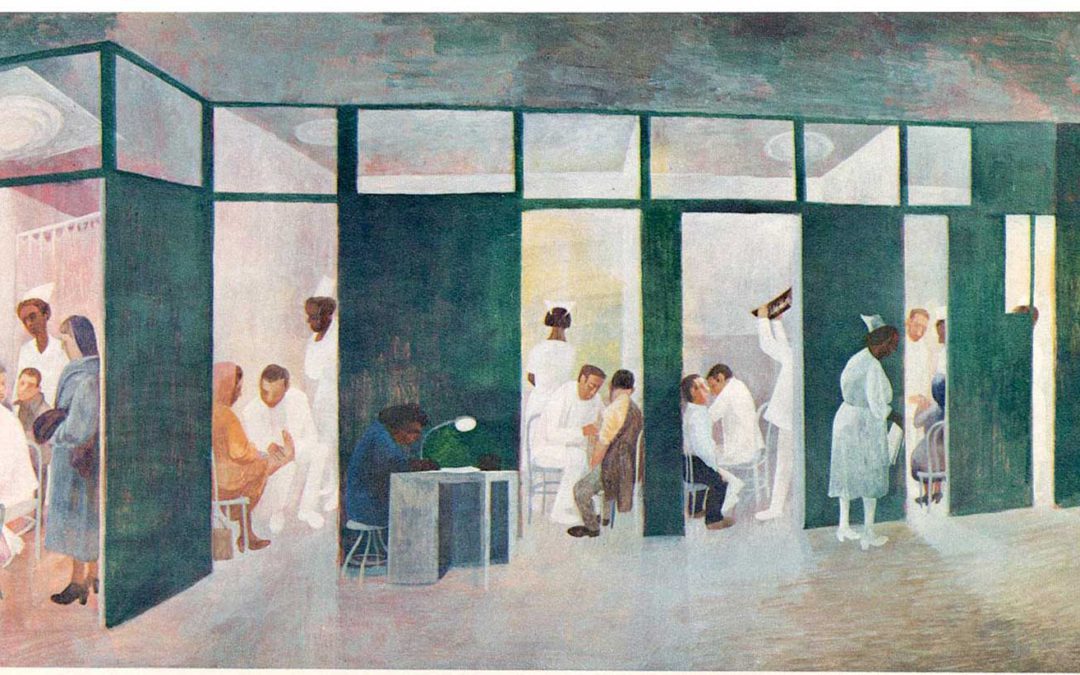

Bernard Perlin

In One-Man Show, Michael Schreiber chronicles the storied life, illustrious friends and lovers, and astounding adventures of Bernard Perlin through no-holds-barred interviews with the artist, candid excerpts from Perlin’s unpublished…..

Faryda Moumouh

Since I was young I was already drawing, watching, registering details from the things I saw. It was an urge and I had the feeling I was chosen by a visual language, which I pursued. I went to art school when I was 14 and it made me discover…..

Agustin Martinez

“Dancers don’t always know what they are doing”, “Revelations from a sailor from Rotterdam” and “The past is alert and ready” are just a few of the many intriguing titles of the work by collagist Agustin Martinez; a fellow countryman of Pablo Picasso…..

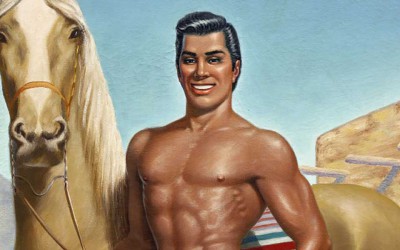

George Quaintance

George Quaintance was an artist ahead of his time, a man who forged several successful careers, yet never enjoyed mainstream fame. Had he been born a few decades later, we might know him today as a multi-tasking celebrity stylist, as a coach…..

Sonia Delaunay

Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979) was a key figure in the Parisian avant-garde, whose vivid and colorful work spanned painting, fashion and design. Tate Modern presents the first UK retrospective to assess the breadth of her vibrant artistic…..

Rurru Mipanochia

Rurru Mipanochia is a 25 year old, Mexican illustrator. Her drawings represent ancient pre-Hispanic sexual deities, transvestites and transseksuals, in order to promote dissident sexualities and to create a visual questioning about beauty…..

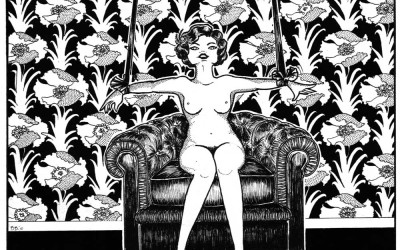

Allen Jones

Three women, wearing black leather fetish gear, produced by the same company that supplied Diana Rigg’s costumes in The Avengers. One of them is on all fours and the glass top on her back awaits your drink. The second one wears thigh high…..

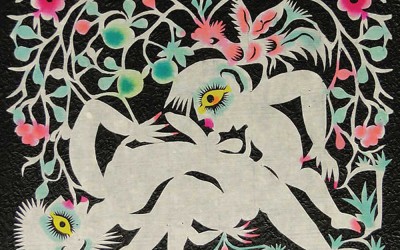

Xiyadie

Paper-cuts originated in Eastern Han Dynasty China (AD 25-220) and are hung on windows or doors for good luck. But instead of the usual decorative flowers and birds, Xiyadie, whose pseudonym means ‘Siberian Butterfly’, portrays graphic and…..

AMVK

Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven is known for creating a diverse body of work in painting, sculpture and installation that has made her among the most important Belgian artists of her generation. She embraces a complex array of subjects, including alchemy,…..

Jennifer Nehrbass

Someone once wrote that she was dismantling the roles and stereotypes of beauty and femininity, examining the psychology that leads women to go to extremes to maintain beauty and style. Needless to say that our brain got tickled so we…..

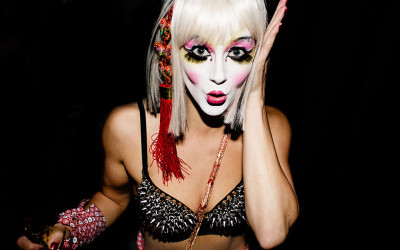

Betty Black

Betty Black started off as a name, just a made up name. An alter-ego that I created for myself in an attempt to perfect one distinctive style of work, rather than end up with a variety of mediocre crap, after having just coasted through a pointless…..