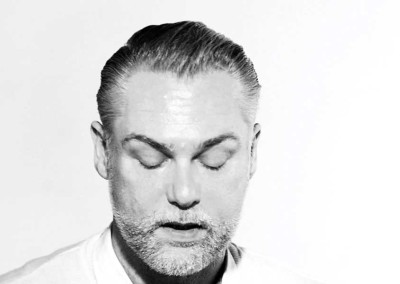

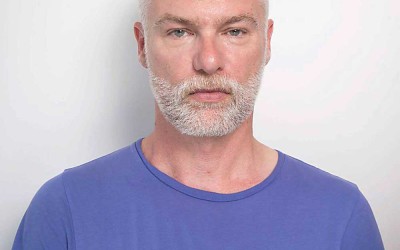

Jonathan Kemp

Text JF. Pierets Photos Rudy Thewis

Jonathan Kemp won two awards and was shortlisted twice for his debut London Triptych. Gay bookstore Het Verschil in Antwerp, asked to interview the British author for a live audience due to the Dutch translation of his novel, Olie op doek. A conversation about history, gay writers and a fascination for language and sex.

In London Triptych you tell three stories. There’s the rent boy Jack Rose in the London of the 1890s, of the 1950’s with painter Colin Read and male escort David, living in the London of the 1990s. The three stories explore the subculture and underworld of male prostitution. You seem to know quite a lot about the subject matter?

I did a lot of research in one way or another, and I was very interested in giving a voice to the voiceless. Male prostitution is a minority within the society of prostitution. Most of the historical focus has always been on female prostitution so they’re like a minority within a minority. As a writer you’re always trying to find a perspective that has not been tackled before and this seemed like a really interesting angle.

London Triptych started out as a short story called ‘Pornocracy’, which told the tale of Jack Rose, one of the boys who testified against Oscar Wilde in 1895. Is Jack historically correct?

Jack starts to work as a telegram boy and then he got involved in prostitution through this man called Alfred Taylor. Taylor really existed and supplied boys to Wilde so there are elements of truth from what I had gathered on research. If it weren’t for the fact that Wilde had been arrested and in prison, it would be even harder to find material on the subject matter. Ironically, given the negative outcome for Wilde, that kind of stamped it in the history books in a way that it wouldn’t have been otherwise. The transcripts of the trial have been very useful. Jack himself is an invention. He’s a mixture of a lot of different boys Wilde played with – he called them Panthers. Their danger appealed to him, their lack of gentility. He was a well-educated, upper middle class man so he liked their roughness, this spontaneity that he didn’t find in his immediate circle.

You seem like a big Wilde fan.

I have loved Oscar Wilde ever since I was a teenager. As I got older and came out myself, I got more interested in gay history. Wilde almost became this figurehead. The idea that he established in many ways, the parameters, the identity that was to go on in the 20th century. The concept that he is almost the prototype of the modern homosexual. He gives it a shape, a voice and a way of being. That was always fascinating to me. I often think the work is overshadowed by his life but I find him an incredible wordsmith. The poetry and ideas in his books have always appealed to me.

Your love of Wilde, the fact that London Triptych is populated by rent boys, models, aristocrats, artists and gangsters,… are you a little nostalgic?

I must say that Jack became my favorite character, that was my favorite piece to write, What appealed to Wilde in these boys is what appealed to me when I got under Jack’s skin. There must have been many Jacks in London at that time and the more I read about queer history, the more I became interested in trying to represent that minority voice.

The minority voice stays but times are changing.

Jack could go to prison for what he was doing, but David, the male escort in the 1990s, is free because of the change in the law in 1967. It’s sort of a history of gay liberation and the humanitarian progress during the century.

The book is filled with sex but it remains sexy instead of becoming a dirty story. It’s a thin line between what your write and pornography.

I’m fascinated by the way that language expresses human experience. Pornography is the most straight forward way sex can be represented. It has a very specific aim and that is to turn you on. There’s nothing wrong with that but it felt a bit limiting to me. I’ve always been attracted to writers like Jean Genet, who wrote about sex in a much more poetic way. For me it was essential to the book that sex had to appear but not in a sort of bashful way. The most interesting thing is often ‘what goes where and who does what to whom’, so I wanted to find much more different metaphors and to describe the emotions rather than the mechanics.

When I read the book if felt like all 3 characters were imprisoned. Because of love. Is that so or is it just my imagination?

As much as sex was an important aspect, love was also. When it became clear to me that this was going to be a novel about prostitution, I wanted to write three love stories. Love coming from the least likely places for example. They are very tragic love stories and I wanted to overturn the cliché of the hard-bitten prostitute who is incapable of love. So love and that trajectory of love is very important.

You ran a theatre company in the 90’s. Why did you switch from that to writing novels?

Writing theater plays was actually a diversion from writing prose. I have always written novels. The first one I wrote was when I was about 17. But I didn’t really pursue it very hard. Every writer gets rejected by publishers but when I got the letters I gave up quite quickly, thinking it was no good. At that time I was living with an actor who wanted to do his own plays so I thought ‘how hard can it be?’ We started of with monologues, it was a one-man show, and after a while I added more characters and got more confident with each play we did. When the company disbanded because there wasn’t enough money in theatre – even less than in books – I went back to writing prose. So London Triptych was the first novel I wrote after the excursion into the theatre.

Your second book is called Twentysix. It’s not a novel nor is it a collection of short stories. I wrote down: ‘Poems about sexual encounters between men. One of every letter of the alphabet’. It’s completely different from London Triptych

It is, but I think it picks up on some of the themes of London Triptych. When I was writing about London and its sexuality, I was trying to gain some originality or poetry in the descriptions. I wrote Twentysix almost immediately after the novel was finished. At first I just wrote down these short episodes, these short encounters. I was exploring language and post structuralism, reading Derrida, Bataille, and wanted to experiment. Midway through the book I considered what to do because I could go on writing about these sexual encounters and publish this huge volume, so I had to put a limit to that. 26 seemed like a slim manageable number.

I read on the net that you once said; ‘I think sometimes being gay has led me to broader horizons than it otherwise would be.’

I think straight comes with a script. You are aware of the life trajectory you’re expected to follow. The model you’re expected to conform to. You’re going to get married, have children, a mortgage. I’m not saying that all people do – and I know straight people who forge a different path – but I think that, when you don’t have that script at hand, you create new possibilities. You kind of invent a way of being. And there is a sort of courage that comes from having to live outside that mainstream model. There’s a security in that model that is not available to you.

‘There is a sort of courage that comes from having to live outside the mainstream model.’

It’s a different way of being in the world. You have to be more original in the things you are going to be or going to do. Just that slightly greater edge of invention.In London Triptych, David describes playing a game when he was a child, standing on a train track, with all his friends. The game was called ‘chicken’ and was about who could stand there the longest. David always won. This unanticipated courage, that was me. I knew from the beginning that staying where I grew up would kill me. Spiritually.

Being gay is as much about character as having a sexual drive?

Whether moving to London had to do with my sexuality, I don’t know, maybe that was a force of character that made me invent and explore. I do think it had to do with the sexual exploration and with courage, I find it hard to separate the two.

Some gay writers don’t want to be referred to as being ‘a gay writer’. Because they are also a white writer, a male or female writer, an American writer,… Yet you don’t mind being in that category.

I don’t. You can call me a black writer if you want to. I can understand why people are against it but then I think; ‘you are gay and you write, so why not’. I feel that it can work negatively because maybe straight readers wouldn’t go for a gay book. While gay readers will rush to it, but nevertheless will also read lots of straight books. So I understand why that label can feel restricted but I don’t mind. I love to write for gay people. It matters to represent these lives in books. People identify with what they read so why not write for gays. I can imagine that some straight people might find a book like Twentysix quite alien but then again, parts of their lives are alien to me. I’m not trying to write for everyone, I’m trying to write for people who can find something in my work. If a straight reader has an open mind, well go ahead. When I came out, exploring my own sexuality, I discovered there was a whole history of gay men writing. That was great! To know that now, after centuries, you have bookshops filled with gay writers is just fantastic. Its history is very short compared with the history of literature, but to discover people like Genet, Vidal or Capote who were exploring and experimenting was a revelation. By putting a label on it, it allows gay readers to find those books. Because if you are confronted with this huge mountain of literature as a gay man or a gay woman, you are going to want to find the books that speak to you because we are all looking for books that give us alternatives. The alternative to see the world from a different consciousness. So I think if you are looking for gay books and there is a big sign where to look, I don’t mind. I find it very useful. It saves you a lot of time. It’s all about things you want to share.

You are not afraid to exclude readers?

Those kind of closed minds are not the kind of people you want to speak to anyway. I can’t say that I’m never going to read a book by a straight person because they have nothing to say to me. Then you will be missing out so much of the things I’ve read and enjoyed.

You are working on a third book.

Yes, and it’s almost finished. My first two books are very related because I was fascinated about sex and language. My new novel is something completely different. The main character in All There Is + All There Is Not, is a 65 year old woman who lives on a narrowboat in North West London. One day she’s out shopping and she sees the spitting image of her first husband who died 40 years previously. She thinks she’s going mad. She keeps on seeing him and it turns out that he’s not a ghost, not a figment of her imagination but a gay man with a striking resemblance, like people often do. He becomes a portal to her. And like Alice she’s tumbling through a portal to an entirely different life and culture.

Sounds great! Looking forward already.

And last but not least. What’s your most flamboyant future dream?

I would love London Triptych to be made into a TV series. A British 3-part TV drama.

And if you were asked to play one of the characters? Who would you choose?

Oscar, of course.

www.myriadeditions.com/jonathankemp

www.birkbeck.academia.edu/jonathankemp

Related articles

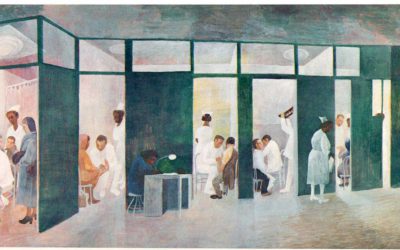

Bernard Perlin

In One-Man Show, Michael Schreiber chronicles the storied life, illustrious friends and lovers, and astounding adventures of Bernard Perlin through no-holds-barred interviews with the artist, candid excerpts from Perlin’s unpublished…..

Annelies Verbeke

That’s a tough one because I don’t like to be put into a box. For me, Thirty Days is just a continuation of everything I’ve written before. I’m working on an oeuvre, which I started in 2003, and hopefully will be able to build up till the end of my days…..

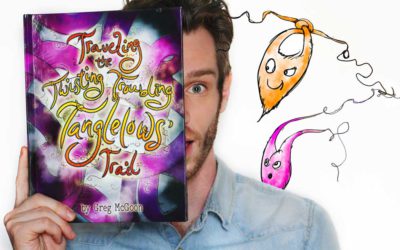

Greg McGoon

Author and theatre performer Greg McGoon challenges the norm of children’s literature. By choosing a transgender princess as main character of the fairytale The Royal Heart and teaching self-acceptance in The Tanglelows, McGoon tries to…..

Ivan E. Coyote

On the day of this interview, New York passed a civil rights law that requires all single-users restrooms to be gender neutral. A decision of great impact on the daily reality of trans people and a life-changing event for Ivan E. Coyote. The award-winning…..

Square Zair Pair

Square Zair Pair is an LGBT themed children’s book about celebrating the diversity of couples in a community. The story takes place in the magical land of Hanamandoo, a place where square and round Zairs live. Zairs do all things in pairs, one…..

Ghosting. A novel by Jonathan Kemp

When 64-year-old Grace Wellbeck thinks she sees the ghost of her first husband, she fears for her sanity and worries that she’s having another breakdown. Long-buried memories come back thick and fast: from the fairground thrills of 1950s Blackpool…..

Leaving Normal

Leaving Normal: Adventures in Gender is creative nonfiction that takes an unflinching but humorous look at living as a butch woman in a pink/blue, boy-girl, M/F world. A perfect read for anyone who has ever felt different, especially those who…..

Amanda Filipacchi

I was 20 when I read Nude Men and I instantly got hooked on the surreal imagination of this New York based writer. 21 years and 3 novels later there is The Unfortunate Importance of Beauty, and Filipacchi hasn’t lost an inch of her wit and dreamlike tale…..

Gay & Night

Gay&Night Magazine started off in 1997 as a one-time special during Amsterdam Gay Pride. It soon however became so popular that it evolved into a monthly glossy. Distributed for free at almost all gay meeting spots in Belgium and The…..

Bart Moeyaert

Bart Moeyaert is internationally famous for his work as a poet, a writer, a translator, a lecturer and a screen writer. He once mentioned on television (on ‘Reyers Late’) that society is often overwhelming, that one is alone with one’s thoughts about…..

Michael Cunningham

We meet Michael Cunningham in Brussels where he is invited as an Artist in Residence by literary organisation Het Beschrijf. Coffee, Belgian chocolates and a conversation with the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Hours……