Annelies Verbeke

Text & photos JF. Pierets

The press called your latest book, Thirty Days, socially relevant. Is it?

That’s a tough one because I don’t like to be put into a box. For me, Thirty Days is just a continuation of everything I’ve written before. I’m working on an oeuvre, which I started in 2003, and hopefully will be able to build up till the end of my days. So for me it’s a clear evolution with its own variations and perspectives, yet they all existed deep inside of me. It did bother me a bit that the book got a very defined market. “What type of book is it?”, “how should we label it?”, are fundamental questions in the literary world nowadays. They say Thirty Days is about the refugee problem, yet that doesn’t quite cover its content. For me it’s about being a good person in a world that doesn’t promote goodness. That’s the essential theme. I always write about what comes my way and the topic of racism and refugees came into view. That’s why I write about them, not because I necessarily needed to write a social critique.

You once said that as a writer you have to write good books, not criticize.

I used to say that as a writer you don’t have to think in terms of social obligation but my opinion on that has changed a bit over the years. Nowadays it doesn’t bother me anymore to use social media or my column in the paper to promote what’s dear to me. For example, foreign writers that nobody’s heard of. We get so little input about European literature that I’m always on a quest to bring suppressed genres and languages to the surface. Did you know that 80% of the books in our Dutch language area are translated from English – a language that almost everybody can read? And only 3% of the books in the American market are translated from other languages? All languages? Just to give you an idea of its dominance in the field and that we are not always aware of how much we are controlled in the choices that we make.

What makes you sit down and write every time?

I think I have to call it an urge. From a young age I was very certain that I would become a writer. The first literary prize I ever received was from a Dutch foundation called ‘Roeping’ (Dutch for Vocation. Ref.), a very Christian word yet I think it kind of fits. I do believe that there is something like a calling. I think that certain jobs like being a teacher or a nurse can only be managed if you have that kind of calling, which is the same for writers. Luckily I got the confirmation that it was the right thing to do.

Did you need that confirmation in order to keep going?

I think that I needed some kind of permission, yes. And of course you have to be a megalomaniac in order to be a writer because let’s be honest, who needs another one?

How do you feel after you’ve finished a book?

After every book there’s the need for time until something else comes bubbling up. I’m always empty when I’ve finished another novel, which is pretty freaky because you never know if it will come back.

Currently you’re writing short stories again.

Yes. And I love it. Each of my short story collections have only one theme, which makes me feel free and happy, and able to look at that one theme from 15 different angles. Whereas in a novel I have to follow the path that I have chosen, be more consequent in a certain train of thought for about a year and a half or two years. A novel asks for a larger consistency whereas a short story is much more playful and offers me another approach. Let’s say it makes me happier.

You’ve been a published author for over 13 years now. Do you still love what you are doing?

When you’re a writer, there’s a constant repetition of events. You finish a book, it gets published, you have to defend it, talk about it, and then you have to start all over again. For the first time it started to feel like a prison after I finished Thirty Days. Don’t get me wrong, I’m very grateful and there is still nothing more liberating than the feeling I have after a great day of writing. There is nothing in the professional field that can replace that. So obviously I’m not going to quit. Yet all of a sudden I saw a glimpse of the dark side. What kind of fate gives you the highest freedom and equally keeps you in prison? I’ll probably get over it, but you need a lot of energy to keep up with the ever-repeating chain of events and I kind of lacked that amount of verve. I was exhausted when I finished that book, but unfortunately that’s the precise moment when the whole circus is about to begin. When I think of myself being in my 70’s or 80’s, I don’t know if I will still have the energy to go through all that again. Sometimes I would like to find something in which I can disappear. At least for a few years. An obvious question now would be; ‘why don’t you just write and not get published?’ But the duality of it all is that a book is not finished before it’s been read. I keep on traversing between a huge gratitude and oppression. Maybe it’s just because I recently became 40. However great my life is, there are still moments when I think ‘is this it?’

Can you imagine doing something else?

I do have those romantic and foolish fantasies about being a hairdresser or a masseuse. Sometimes I would love to have a profession where I can touch people – in a non-erotic manner. That fantasy keeps coming back.

That sounds like an eagerness to please.

I don’t know, maybe I should call it ‘relating’ instead of ‘pleasing’. People wouldn’t even have to thank me for a job well done; it’s really about making them happy

What keeps your mind flexible?

I know it sounds contradictory, but I’ve set out a few rules in order to keep a flexible mind. Every year I want to read 52 novels. There has to be at least one book from every continent – with the exception of Antarctica and Arctica because there’s not much writing going on there – and spread over three centuries at least. It probably sounds more epic than it actually is because it’s quite doable. It allows me to read the writers that you do not stumble upon easily.

‘A female critic once accused me that I was afraid of being a woman. I found that pretty surreal. You might read something neutral in my work, yet that’s who I am. I don’t have to pretend, do I?’

Are there certain things that have determined your growth?

Notwithstanding certain life events that mess you up, I think that the older you get, the more life experience you gain and the more you read, the more you grow. I’m lucky to be able to pour the sad things from my life into literature. Which is often a salvation. Being able to transform your pain into something creative is a huge victory. And that’s a gift. Imagine being a bookkeeper, or a shop owner, how do they handle that?

What do you like to write about most?

If I would have to point out a common theme running through my little oeuvre, it’s ‘what is reality?’, which most of the time is based upon assumptions. In the beginning of my career a lot of reviews spoke about my fascination for madness. Yet I’m not necessarily interested in madness, but I am intrigued by what someone with a psychoses experiences as reality. Even better, you don’t have to go as far as having a neurosis to see that every one of us has another reality. It’s both interesting, funny and tragic how hard people are trying to fit into that. The absurd is omnipresent. Just think about war, or placing a gnome figurine in your garden, just because your neighbors are doing it. There are so many delusions wherein people are finding themselves or basing their identity on. It’s very innocent when it’s about gnomes, but it can also escalate into resistance towards refugees. If you agree that a certain branche of our population doesn’t have any human rights, just because your neighbor is thinking the same thing. Absurdity dwells in the constant threat of chaos. On the one hand you have the efforts to keep it all on the right track and on the other there’s pure escalation. That’s where absurdism comes from. And it’s constantly around us.

Is that what you are doing as a writer? Creating a new reality?

That’s exactly how it feels, but it’s more like filling something in instead of creating. Céline once said that the stories that we write are the invisible castles above our heads which we have to reconstruct on paper, stone by stone. I still find that a great image. When I’m writing I can always feel when it’s good and when it’s not. And not only when it comes to style, rhythm or grammar, but also if it’s right for the story. Which is weird, because this possibly implies that the story is already there. That there’s an ideal, which you merely mirror.

Is it self-portraiture?

I consider myself a parade of people where one takes the lead until the next one takes over. In my novels my narrators were the ones leading in a certain period of time whereas in my short stories, I’m looking at who else is in that parade.

What is literature about?

It’s about insight and all kinds of thoughts and feelings. You have to confront the things that happen to you. It’s an introspection without you being behind the wheels. For me it’s also very double; part of me is writing freely while the other part is controlling the quality of what I write as a reader. And I can tell you it’s not a reader who is easy to please. But then it gets read and criticized and that’s even worse because it’s always colored by someone’s prejudice. I don’t care about someone saying or writing that they don’t like the book for reasons of taste, but I do care if someone offers criticism coming from resentment, or if someone is holding a grudge or just doesn’t like female writers. That said, fortunately there are many literary critiques in which I’m completely understood, which offers a sense of ease.

Let’s talk about the female writers.

I have a lot to say about female writers. When I made my first appearance as a 27-year-old writer I had more of the aura of a rabbit in headlights than of someone with an impressive personality. I can give numerous examples of how I’ve been patronized or intellectually underrated. In the beginning of my career people actually asked me what it was like to be a woman while my male colleagues were never asked that question. But I’m not only talking about men, because for me, feminism is not the opposite of men being against women. Some women are also biased and judgmental about women. And what I definitely cannot stand is being treated that way by people whom I find less intelligent than I am.

Anyhow, I do think people read very judgmentally. People start off with tons of assumptions that they then actually read in the book. I know it’s impossible, but sometimes I wish that things like awards would happen anonymously. A lot of women are still not nominated so I wonder if this would make a difference. A female critic once accused me that I was afraid of being a woman. I found that pretty surreal. You might read something neutral in my work, yet that’s who I am. I don’t have to pretend, do I? The same for men. When a book is from a neutral position, I often find it more interesting – this compared to some Hemingway-ish kind of writing because how many times can one go fishing and hunting? Let’s say there’s still a lot to do on the gender front.

Related articles

Bernard Perlin

In One-Man Show, Michael Schreiber chronicles the storied life, illustrious friends and lovers, and astounding adventures of Bernard Perlin through no-holds-barred interviews with the artist, candid excerpts from Perlin’s unpublished…..

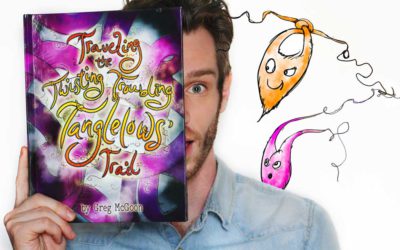

Greg McGoon

Author and theatre performer Greg McGoon challenges the norm of children’s literature. By choosing a transgender princess as main character of the fairytale The Royal Heart and teaching self-acceptance in The Tanglelows, McGoon tries to…..

Ivan E. Coyote

On the day of this interview, New York passed a civil rights law that requires all single-users restrooms to be gender neutral. A decision of great impact on the daily reality of trans people and a life-changing event for Ivan E. Coyote. The award-winning…..

Square Zair Pair

Square Zair Pair is an LGBT themed children’s book about celebrating the diversity of couples in a community. The story takes place in the magical land of Hanamandoo, a place where square and round Zairs live. Zairs do all things in pairs, one…..

Ghosting. A novel by Jonathan Kemp

When 64-year-old Grace Wellbeck thinks she sees the ghost of her first husband, she fears for her sanity and worries that she’s having another breakdown. Long-buried memories come back thick and fast: from the fairground thrills of 1950s Blackpool…..

Leaving Normal

Leaving Normal: Adventures in Gender is creative nonfiction that takes an unflinching but humorous look at living as a butch woman in a pink/blue, boy-girl, M/F world. A perfect read for anyone who has ever felt different, especially those who…..

Amanda Filipacchi

I was 20 when I read Nude Men and I instantly got hooked on the surreal imagination of this New York based writer. 21 years and 3 novels later there is The Unfortunate Importance of Beauty, and Filipacchi hasn’t lost an inch of her wit and dreamlike tale…..

Gay & Night

Gay&Night Magazine started off in 1997 as a one-time special during Amsterdam Gay Pride. It soon however became so popular that it evolved into a monthly glossy. Distributed for free at almost all gay meeting spots in Belgium and The…..

Bart Moeyaert

Bart Moeyaert is internationally famous for his work as a poet, a writer, a translator, a lecturer and a screen writer. He once mentioned on television (on ‘Reyers Late’) that society is often overwhelming, that one is alone with one’s thoughts about…..

Jonathan Kemp

Jonathan Kemp won two awards and was shortlisted twice for his debut London Triptych. Gay bookstore Het Verschil in Antwerp, asked to interview the British author for a live audience due to the Dutch translation of his novel, ‘Olie op doek’. A…..

Michael Cunningham

We meet Michael Cunningham in Brussels where he is invited as an Artist in Residence by literary organisation Het Beschrijf. Coffee, Belgian chocolates and a conversation with the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Hours……