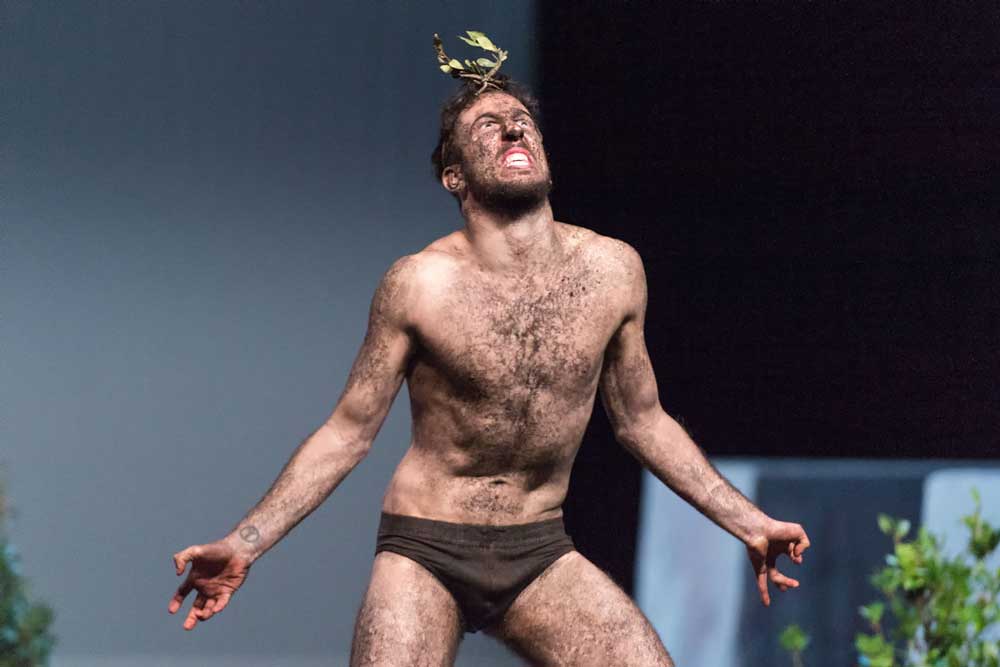

Mount Olympus

Text JF. Pierets Photos Wonge Bergmann & Sam De Mol © Troubleyn / Jan Fabre

It took more than one year for Jeroen Olyslaegers to write the text for Jan Fabre’s 24-hour theatrical performance Mount Olympus, to glorify the cult of tragedy. A labyrinth of time where the actors sleep and awaken on stage, dance and move in the violent, ecstatic proximity of characters from Greek tragedy. One night in Seville Julian and I watched history in the making and we were in awe during every minute of it. A mind-blowing and life changing experience that made us realize that you hardly ever get to experience and recognize a masterpiece in contemporary time. In conversation with Jeroen Olyslaegers. About stripping down emotion, writing at the very top of your abilities and the meaning of life.

How does one start such a huge project?

The first thing I did was reread all 32 Greek tragedies. I got inspired and then buried them. One year later, in June 2014, we started rehearsals. Since it was impossible to write the text beforehand and give the actors a syllabus of 200 pages – everybody would get a panic attack – I wrote during rehearsals. I reinvented and introduced my own themes by using the original material in a new way. There is not one sample of the original texts in any of the monologues, yet some of it is pretty close to the principal characters.

You not only worked, but also slept within the proximity of the rehearsal room.

That was my one condition when I accepted Jan’s offer. I wanted to be close to the rehearsal room because the performance is about dreams, about problems with sleeping, so it was clear that my own situation was going to be very influential. Rehearsing and writing Mount Olympus was like a marine boot camp where your head get’s to an amazingly trained level. When I had been writing for half a year, I felt like a Lamborghini. To give you an example: in October I needed two or three hours to write a monologue, in March I needed fifteen minutes to write the same piece in both in English and in Dutch. You are inside this Greek monster and you know which way to go. Like a racing car driver who knows every turn of the circuit. As a writer it was a unique position to be in and a once in a lifetime experience. Who would do a 24 hour performance after this? It’s almost impossible.

It’s quite the tour de force to comprehend 24 hours of text and images. How do you tackle such an overpowering quantity of material?

One of the things we discussed a lot was if we needed to contextualize the characters. Do we need to explain to the audience who Medea, or Dionysos is? We decided to try but it soon turned out to be completely stupid. We had to get rid of the hang-up that the audience needed a context, needed to know about Greek culture and ancient tragedies in order to be able to enjoy the performance. For us, it was tabula rasa. But the moment we knew the people did’t need this cultural baggage, it was a breakthrough. Another turning point was the moment Jan challenged/ composed the first and the final part, which was the first thing that came together. You have to realize that for every scene that you see, we had four other scenes so we’re literally talking about thousands of scenes, all with their own small or larger variations. Assembling such a volume of material is madness, yet when we all saw a sketch of the first and the final part, we suddenly had a clear sense of direction. We suddenly knew we could do this.

It’s not the first time you have worked with Jan Fabre.

Five years ago we made Prometheus together. Working with Jan it so intense that it’s incomparable to any other director. Jan puts you on the edge of a cliff and gives you a push. You fall, that’s it. For one year we worked on a level where none of us was convinced that we were going to make it. I remember the first time we tried out the complete 24 hours; we started out at 5 PM, the sun was still shining, and at 8 in the morning we said to each other, “what are we doing? This is crazy!”.

You write novels, which is a very solitary profession. How does it feel to co-create?

I love both. A combination of solitude and collaboration. The interaction with a group also feels fantastic. You get totally different ideas and I feel I’m becoming a better artist when I work with other people. Of course there are some conditions like having the same focus and the same intensity. Let’s say Mount Olympus made it impossible to work on a theatre project with no intensity.

Did you have faith in the outcome?

We were worried about the performers who had to give every inch for the entire 24 hours. They have to be in control of their bodies. We were worried that they would hurt themselves due to sheer tiredness because people react totally differently when they lack sleep. And to handle that tiredness is different for everybody. Some need 45 minutes, others need 3 hours, and some of them don’t want to sleep at all. At every point of the process we didn’t know what was going to happen next. I had no idea that Jan was going to rehearse the entire piece in every detail, which was totally crazy. For me it’s still a miracle that everything you see has been rehearsed over and over again. If somebody jumps from a table, it’s rehearsed to happen exactly at that moment. There is absolutely no improvisation. Can you imagine the amount of time you need to write and direct 24 hours of performance to the smallest detail? It’s almost impossible. How do you cope on a mental level? The performers rehearsed so much and for such a long time, that they found themselves in a dream state where they could do almost anything.

I guess Mount Olympus was quite up your alley because of your fascination for the concept ‘time’.

Afterwards it’s weird to reflect on what we did with time. For me time is linked with catharsis; we have this old 19th century idea of theatre. We expect to look at a play, in a dark room filled with other people and expect a catharsis. For me it’s a strange idea to expect an insight from a 2 or 3-hour play. What actually happened in ancient Greece were these big Dionysian festivals, competitions between different playwrights. People came to the theatre at dawn and watched for about 12 hours. They had dinner, had a drink, it was a coming and going and the catharsis was the entire experience. That’s what we do with Mount Olympus. We actually stretch time, where the catharsis is totally different and much more violent for the audience to capture. After a couple of hours we strip away the intellectual human layer and what remains is pure emotion. It’s not uncommon that people start to cry because there’s no protection left. We’ve demolished it. That’s the Dionysian power of it. I actually have Dionysus say this in the beginning of the piece; “we’re all going to get you really, really crazy. We’re going to get you mad”. Which is what happens at the end.

‘For me art has to be activism, otherwise it doesn’t work. For other artists it can be a quest of beauty, but for me it’s a tool to activate people.’

And every time the performance gets a standing ovation for more than half an hour.

We never had a Mount Olympus performance where the audience was not connected. Putting more than a year’s work into a project, makes the love you get in return very intense, very moving. The level is magic. We wanted that, but we had no idea it was going to be this euphoric.

Mount Olympus is a statement against the pressure to produce quick and cheap entertainment. Has this experience changed your own way of creating?

It taught me to go to the essence, to not be afraid of using emotions – even when they’re strong and hard – and to get rid of the last reminisce of irony that I had. I still like a good joke and I like sarcasm but for me, writing is for real. As a writer I want to kick you in the heart and in the head. Mount Olympus has taught me to become much more intense. Intensity is everything. You have to go for it and not wait anymore. What I feel now in a very urgent way, is something that’s happening to the world at this point.

The performance is a political metaphor for society now and back then.

Mount Olympus starts with two guards, blowing a message in the ass of another and talking about an ecological nightmare and the apocalypse, which sets the political tone of the entire piece. It’s about war and the way we tend to fuck up our karma by breathing hate the entire time. Every Greek play is only about one thing; there’s a bill to be paid and somebody has to pay it. I connected this to the tragic times we now live in. Think about King Oedipus; because he killed his father and married his mother, a plague broke out in Thebes. But he doesn’t know that. He asks people to check why there is a plague. They all return saying that he is the reason but he doesn’t believe them, he just keeps sending people to go and check. This is what’s happening today also. Ecologically we’re on the brink of a big disaster and we’re going to have to change our lives to pay the bill. That’s what Mount Olympus is about: there is something that has to be reckoned with.

Are you saying that nothing has changed?

I think blindness has increased. We no longer have the confrontational insight of Greek tragedy. People think that theatre is entertainment, I think theatre is drugs. It’s an attack to your system, an attempt to transform you.

If it’s not entertainment than it’s activism.

Definitely. For me art has to be activism, otherwise it doesn’t work. For other artists it can be a quest of beauty, but for me it’s a tool to activate people. And that’s what we did with Mount Olympus. If you look at Jan’s theatre plays you see that they are always based on provocation. To wake you up. And sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, yet you feel that there is this activating principle. I think that’s why we’re friends, we understand each other on that level.

I once heard you say that Greek mythology is your spiritual landscape. Can you elaborate?

My spiritual landscape corresponds to the Greek, but also the Celtic times before Christianity. It’s a very creative time. You have monotheism – which I find very boring because it’s like a block of concrete, and you have polytheism, which is very liberating and why I call myself a Satyr. There’s this great sense of play. Context is everything in Greek mythology. It’s like quantum mechanics but based on mythological thinking. What I think and what I do is invest time into taking these gods seriously. Trying to give them a place in my work – like Mount Olympus, but also in my daily and practical life. I think the Greek gods are not dead, they are among us. It’s a totally different way of looking at spirituality and religion. Especially now, when every religion is becoming dogmatic again, we need some liberation by introducing play.

What do you do to tap into your creativity?

I do something physical. I walk, or go for a swim. It used to be just reading but now it’s much more listening to nature and going out. Everything that I see is a gift that I can use, so there is no coincidence in my life. The great thing about writing is that it enhances your feeling of observation. When you write a novel, you have this mental space where the novel lies. I’ve just finished a novel about Antwerp during WW II, and I have this specific image of the city in my head. I know how the streets used to look 70 years ago so I can walk through Antwerp by just closing my eyes. I also go to that place to meditate. I can sit in a bar, have a coffee and be in 1942. I go to that mental space to solve plot problems but also to chill. And it becomes more relaxed when you’re on a bike or on a walk.

What do you hope to be your lasting significance as an artist and a human being?

Those two things are very combined now. I used to be just a writer, but now activism has mixed everything together. It’s a difficult question. I think I want to leave this lasting impression of love for humankind. Everything that I currently do is situated on what the Indians call the heart chakra, both in and outside my writing. I want to link people to each other because basically I think we need to invent a spirituality that connects people to each other. Whether you’re Muslim, or Jewish, or an atheist. Like Moses, we can use two stone tablets with one sentence carved onto each one of them. The first is “we’re all one”, which was proven by genetic science 50 years ago, and the other one is “we all share the same planet”. The way we live needs to reinvest respect for the planet, consider her as a mother instead of something that we exploit. I’m always trying to combine these things in my work because there’s a sense of urgency to act. That kind of energy is the lasting impression I would like to leave behind.

I read this beautiful quote by Viktor Frankl, stating that “Ultimately man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked”. Any thoughts?

It also means “know thy self” and it is one of the most difficult questions there is. But also the most beautiful. “To become what you want to become in life is the most difficult thing ever” is one of the sentences that I use in my new novel. It’s the most difficult and at the same time the most provocative thing to do. Because the majority seem to want you to remain not who you are, but who they all are. Being like everybody else. Yet everybody has the capacity to fly and the capacity to become who you think you want to become. It can take your entire life to get there, but that’s the spiritual beauty of the whole thing. If everybody does this, focuses on that, or if we have this critical minority who’s focused on that, the world would be a better and more interesting place. And I must say that it becomes easier with time. The older you get the more you realize that what happens in your life are actually forces, pushing you to your destiny. I have this big storytelling tradition in my family but I started out as a post-modernist writer and an intellectual deconstructivist. Now I’m liberating myself with every book and every theatre play to get closer and closer to what I’m trying to become and what I am destined to be; a pure storyteller.

Related articles

Jorge Clar

We caught up with poet and performance artist Jorge Clar in his home in New York, and talked about words, sounds, and image. An ideal for living. Initially, you came to New York because you wanted to be close to the disco scene. That was…..

Kabarett der Namenlosen

Ever since the beginning of Et Alors? Magazine we have had a soft spot for singer, model, bon vivant and muse Le Pustra. Being inspired by the same artists and artwork such as the Oskar Schlemmer’s costumes for the Bauhaus movement…..

Shania LeClaire Riviere

When you’re visiting Provincetown in the summer, you’re in for a creative treat. Every other Friday, performance artist Shania LeClaire Riviere dresses up and takes his work onto the streets to show his latest creation. Art on Shania is a walking art…..

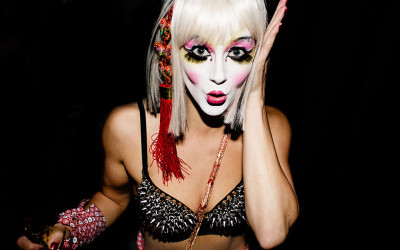

The Vivid Angel

She’s the queen of alternative performance, won the Twisted Cabaret Crown World Burlesque Games in 2014 and is this edition’s cover model. But most important, sometimes you just meet one of those people who make you think YAY!…..

Criaturas

Criaturas is the name Saskia De Tollenaere and Olivier Desimpel gave to the world they created for everyone who dares to dream. An experience concept where their passion for theater, art, fashion, beauty, spirituality and emotion merges in the form…..

The Cabaret Switch

When two of Et Alors?’s favorite artists decided to do a personae switch, a smile appeared on our faces. Queen of fetish cabaret and diva extraordinaire Marnie Scarlet, transformes into Mr. Pustra, Vaudeville’s Darkest Muse. We leave it up to them to…..

Extravaganza

Lars de Valk founded Extravaganza. The first extravagant bears, lesbians, muscle boys, club kids, drag queens, fag hags, fetish clubbers party with a positive vibe in Antwerp, Belgium. Bringing you happiness with themes such as Asian Persuasion, Sinners…..

Mister Joe Black

‘A constantly evolving cabaret chameleon, blurring the lines of decency within entertainment and continues to drive music and performance into strange new realms’ and ‘No stranger to the absurd, Joe Black creates a world where the shocking is the…..

Mr. Pustra

“I wouldn’t mind appearing on the cover of Vogue.” Mr. Pustra aims for no less than the sky when he is asked about his goal for 2012. Knowing one should never run before one can walk, he tests the waters with an interview for Et Alors? Magazine…..

Marnie Scarlet

Although the definition of Burlesque says “a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects”, one cannot erase the image of Von Teese…..