In One-Man Show, Michael Schreiber chronicles the storied life, illustrious friends and lovers, and astounding adventures of Bernard Perlin through no-holds-barred interviews with the artist, candid excerpts from Perlin’s unpublished…..

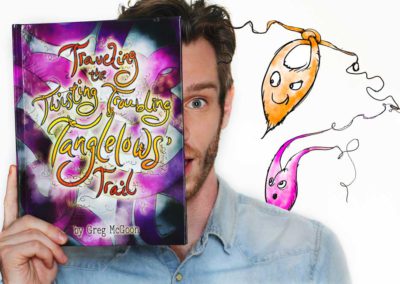

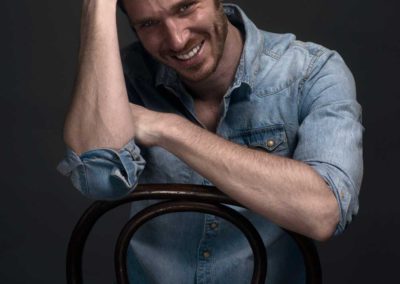

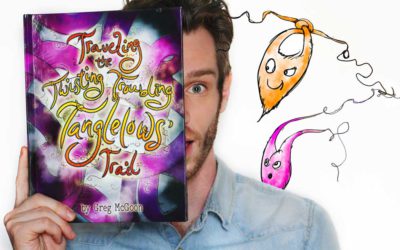

Greg McGoon

Greg McGoon

Text JF. Pierets Photos Courtesy of Greg McGoon

Author and theatre performer Greg McGoon challenges the norm of children’s literature. By choosing a transgender princess as main character of the fairytale The Royal Heart and teaching self-acceptance in The Tanglelows, McGoon tries to establish a healthy open-minded relationship between parent and child. A conversation about imagination, gay characters and overcoming obstacles.

You studied psychology and political science. How does one become an author of children’s books with this background?

There’s a theatre program in my hometown and that’s where I fell in love with both theatre and working with children. This background basically evolved into writing for – and learning to connect with – kids through theatre, an art form not only about acting but something that also strengthens your social skills and your engagement. I think dealing with kids, theatre and art, while keeping the psychology I studied in my mind, naturally developed into writing down stories. It just happened as I was trying to process my own growth and understanding of the people around me. I realized that my words would have a broader reach if I found ways to adapt them to reach out to children.

Your imagination immediately takes off running in your first book, Out Of The Box. A story about the limitless places our creativity can take us to.

I kind of wrote Out Of The Box for myself, when I was developing a project with children on creative arts. Rather than write some angsty melodrama of my own life, I wanted to rediscover the creativity and imagination that I felt I had lost long ago. I wanted to find some solutions to my own struggles and challenges in a more universal, but also playful way. This book is not only about the simplicity of children playing with a cardboard box. It’s about maintaining and owning your imagination in order to make honest connections with others, even though that can prove challenging. It was my response to the concept of imagination and allowing that magic out of the box once again.

It sounds like your personal pursuit became a tool to help others.

I did. I thought I’d rather live with the possible pain of expressing my feelings, than live with the pain of denial. My personal life story became so dark and I got so tired of living in that darkness, tired of denying things, that I had to take ownership of myself and of my self worth. Writing these children’s books and trying to work past this fear of speaking about your feelings was very important. Because once you’re an adult, it gets a lot harder to start opening up all of a sudden. But when you’re a child you get into that habit of not only talking about your feelings, but also learning how to do so. There are so many ways to express yourself, but some ways are more healthy and effective than others. If children start recognizing that and start being comfortable, it will help society as a whole.

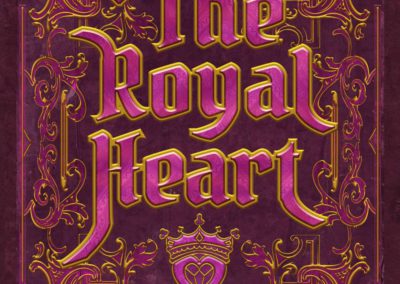

Your second book, The Royal Heart, is a fairytale. The first fairytale ever with a transgender princess.

Like many kids I had a childhood fascination for Disney and the exploration of the origin stories. What fascinates me in fairytales is not just the lesson they can teach, but how they’ve been shared over time and what has been changed due to the time that they were written. They are evolving and are adapting to society’s influence in a lot of ways. Children are connecting and relating to that. When I grew up, all I was seeing and reading were all these beautiful men and women falling in love with each other. I could connect with the essence of the story, I could connect with the love, but the visibility of it was limiting. Fairytales are magical, grand and beautiful, so why should people be excluded from that?

Why use the transgender theme?

It just so happened that the idea of a transgender character fitted the essence of what I was trying to convey. Transformation is a common theme in fairytales; Ariel’s goes from fins to legs, the frog becomes a prince, a princess becomes a swan, and so on, and most of those transformations are due to an external force. I never intended the book to be about being transgender, because that’s not something I personally experienced, but it’s about the love for everyone around me. The acceptance of that as being a part of life. If somebody comes to me and says “this is who I truly am”, there’s no part in me that would ever ask “why?” That’s not a question that comes into my mind, I’d rather say “thank you for sharing.” A lot of people are still stuck on the “why?” Why are you a woman, why are you a man, why are you gay? However, there is no “why” to begin with. It’s a reality that needs no explanation. It’s just about love.

‘The book can be a message for parents to show their children that this character worked up the courage to express their true self. That no matter what that is, their child can feel that way too.’

Did you intentionally use a medieval setting to make it more timeless?

Yes, I wanted it to look like it’s been around for many years because transgenderism is not new. And history has a way of denying the voice and the human experience when it is not understood. The book is very minimal, yet I was very careful in choosing the words to take it a little bit further then just about gender. For me it’s also about taking on the responsibility of self and becoming a leader. I want people to look at it and wonder if hundreds of years ago there actually was a prince who could never fully realize himself. We’re talking about a whole spectrum of human life that has always been around. It’s not that all of a sudden people are being born who identify in a different way. It’s just that those voices are finally starting to be heard. We get so caught up with this idea of male-female that we lose sight of just living life. And there are so many ways to live life that I don’t think it has to be dictated how that should be. Let’s just try and live together instead of trying to impede on other people’s lifestyles. We don’t have to hold hands and get along, but we do need not to abuse each other. And that’s what The Royal Heart talks about; it’s about celebrating life.

A true idealist?

I don’t know how I became such an idealist all of a sudden since my mantra through my mid-twenties was “I’m gonna die alone!” I was this melodramatic person until I finally realized I was only going to die alone if I forced that upon myself. I had to believe that there was more to it, and since I can’t be the only one in the world with those feelings I started sharing my stories and my writing. Because why can’t the LGBT community have those unrealistic, magical, love at first sight, fairytale stories, if everybody else does?

I’ve said you’re working on a book about a gay prince. Are you looking for a fairytale character you can relate to?

Well, I still want to write this epic adventure I was looking for when I was a kid. Having stories that represent LGBT characters is adding to the positive visibility that hasn’t been around for children. You can only have so much fun looking at blog posts of genderbending Disney characters. We’ve all seen those, and it’s great, but where are our characters? I’m not trying to be groundbreaking or evolutionary, I just want to have a character that happens to love men.

How would you convince a parent to buy an LGBT themed book for their child?

Having an LGBT character doesn’t necessarily make a book LGBT themed. The Royal Heart is not LGBT themed, nor is the story of the prince I’m developing. The main theme is love. To establish a healthy relationship between parent and child, you have to be open to each other. The book can be a message for parents to show their children that this character worked up the courage to express their true self. That no matter what that is, their child can feel that way too. They can come to them, no matter what they have to say, and that they are going to be ok with it. So it’s an invitation to children to know that if their parents share this story, that they have their full support of their full existence.

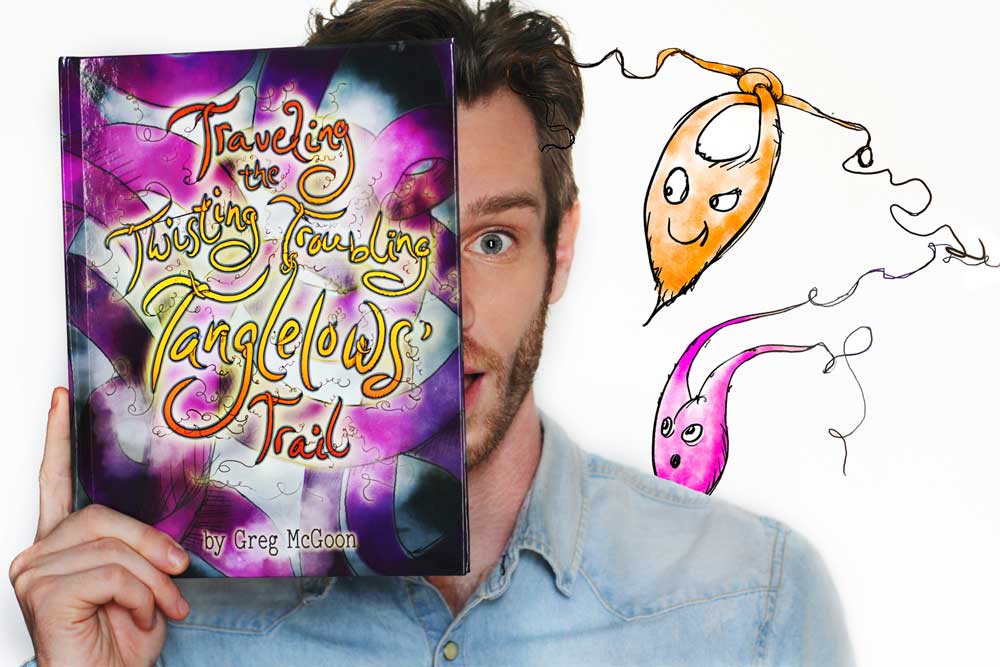

You recently released your third children’s book, Traveling the Twisting Troubling Tanglelows’ Trail. What’s it about?

It’s a rhyming, poetic story that deals with creatures that live inside your mind and tangle everything up, making you feel that you are worthless. In this book I’m saying that life is full of challenges, and that you’re might feel useless, but you have the ability to start untangling that. With this book I hope to introduce some practical applications to an abstract thought. Children need to understand that feeling unhappy is sometimes part of the beauty of life. And while bad things can happen, good things can happen also. The characters are saying that pain exists, but that joy can be found. You’re going to face obstacles, but you’re only going to be able to overcome them once you start to realize that you have the strength to do so.

Related articles

Bernard Perlin

Annelies Verbeke

That’s a tough one because I don’t like to be put into a box. For me, Thirty Days is just a continuation of everything I’ve written before. I’m working on an oeuvre, which I started in 2003, and hopefully will be able to build up till the end of my days…..

Greg McGoon

Author and theatre performer Greg McGoon challenges the norm of children’s literature. By choosing a transgender princess as main character of the fairytale The Royal Heart and teaching self-acceptance in The Tanglelows, McGoon tries to…..

Ivan E. Coyote

On the day of this interview, New York passed a civil rights law that requires all single-users restrooms to be gender neutral. A decision of great impact on the daily reality of trans people and a life-changing event for Ivan E. Coyote. The award-winning…..

Square Zair Pair

Square Zair Pair is an LGBT themed children’s book about celebrating the diversity of couples in a community. The story takes place in the magical land of Hanamandoo, a place where square and round Zairs live. Zairs do all things in pairs, one…..

Ghosting. A novel by Jonathan Kemp

When 64-year-old Grace Wellbeck thinks she sees the ghost of her first husband, she fears for her sanity and worries that she’s having another breakdown. Long-buried memories come back thick and fast: from the fairground thrills of 1950s Blackpool…..

Leaving Normal

Leaving Normal: Adventures in Gender is creative nonfiction that takes an unflinching but humorous look at living as a butch woman in a pink/blue, boy-girl, M/F world. A perfect read for anyone who has ever felt different, especially those who…..

Amanda Filipacchi

I was 20 when I read Nude Men and I instantly got hooked on the surreal imagination of this New York based writer. 21 years and 3 novels later there is The Unfortunate Importance of Beauty, and Filipacchi hasn’t lost an inch of her wit and dreamlike tale…..

Gay & Night

Gay&Night Magazine started off in 1997 as a one-time special during Amsterdam Gay Pride. It soon however became so popular that it evolved into a monthly glossy. Distributed for free at almost all gay meeting spots in Belgium and The…..

Bart Moeyaert

Bart Moeyaert is internationally famous for his work as a poet, a writer, a translator, a lecturer and a screen writer. He once mentioned on television (on ‘Reyers Late’) that society is often overwhelming, that one is alone with one’s thoughts about…..

Jonathan Kemp

Jonathan Kemp won two awards and was shortlisted twice for his debut London Triptych. Gay bookstore Het Verschil in Antwerp, asked to interview the British author for a live audience due to the Dutch translation of his novel, ‘Olie op doek’. A…..

Michael Cunningham

We meet Michael Cunningham in Brussels where he is invited as an Artist in Residence by literary organisation Het Beschrijf. Coffee, Belgian chocolates and a conversation with the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Hours……