In One-Man Show, Michael Schreiber chronicles the storied life, illustrious friends and lovers, and astounding adventures of Bernard Perlin through no-holds-barred interviews with the artist, candid excerpts from Perlin’s unpublished…..

Ghosting. A novel by Jonathan Kemp

Ghosting. A novel by Jonathan Kemp

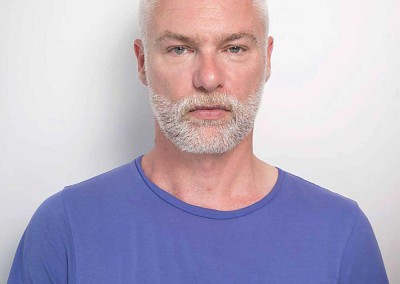

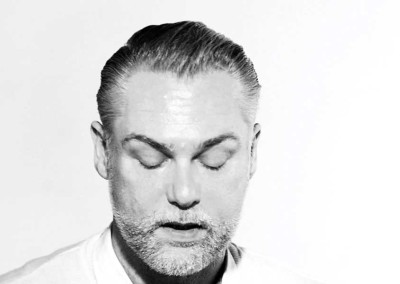

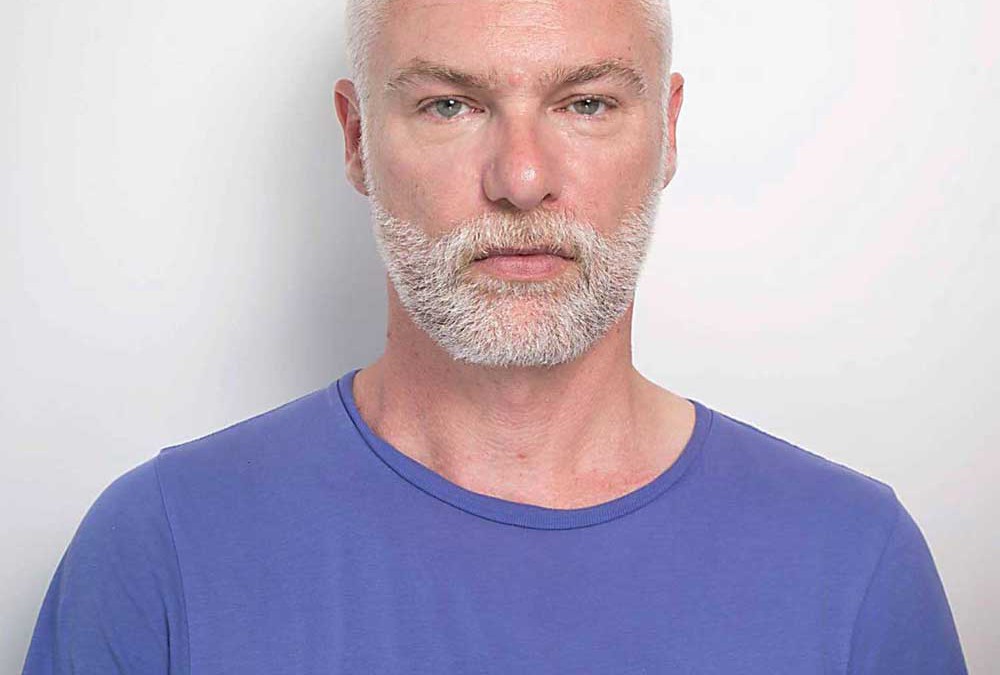

Text JF. Pierets Photo Christa Holka

When 64-year-old Grace Wellbeck thinks she sees the ghost of her first husband, she fears for her sanity and worries that she’s having another breakdown. Long-buried memories come back thick and fast: from the fairground thrills of 1950s Blackpool to the dark reality of a violent marriage. But the ghost turns out to be very real: a charismatic young man named Luke. And as Grace gets to know him, she is jolted into an emotional awakening that brings her to a momentous decision. We’ve talked to Jonathan Kemp, about his latest novel, Ghosting.

The subject matter of Ghosting is completely different from London Triptych, 26 and The Penetrated Male. What happened?

I suppose I got bored with writing about cock (laughs). I think I said everything that I had to say about gay male sexuality in the first three books. Having said that, my forthcoming book, Homotopia?, a nonfiction book, is about homosexuality. It’s basically my Masters thesis, written in 1997, before any of those other three books. But all this considered, I believe as a writer you get seduced by a story or a character, and the origin of Ghosting is rooted in a journey that my mother made in 1967 when I was 8 weeks old. My father was in the Royal Air Force and got stationed in Malaysia. He went ahead because she was pregnant with me and she stayed behind to give birth in Manchester. After that we flew out there. Obviously I don’t remember a thing about it, but in my head it became this magical, mythical journey of a working class young woman who’s never been outside of the UK, traveling with three small children from one world to another. My original conception was to use the journey as a central metaphor, the notion of a journey. But then the character of Grace came to me and things developed from there.

So it’s not a novel about your mother?

Not in any sense. There are massive differences in terms of Grace’s personality and the things that occur to her; my father didn’t beat my mother nor did he die. I’m not interested in writing an autobiography; I’m interested in expressing different strategies, events, and the truth of an emotion. But again, a lot of writing in general comes from asking yourself the question, “What if?” What if she’s relieved to find her husband dead upon arriving in Malaysia? He was a vile alcoholic and she didn’t want to go back to him anyway. What if she loses her daughter from whom she felt very estranged? I wanted to explore the concept of grief, but I also wanted to challenge some maternal issues in a We need to talk about Kevin, kind of way: in that, you might not necessarily like your child.

Why write about grief?

In many ways both London Triptych and 26 explore sexual grief, but it’s not really noticed upon. Grief is something that I’m fascinated by. It comes in many forms and I think, like most emotional realities, it’s experienced in radically different ways. Sometimes grief is considered inappropriate, as if it has a certain expiration date after which you have to get on with it. The whole capitalist, utilitarian mindset generally dictates that; they give you a month to grief and then you have to get back to work, be productive. It was that lack of compassion that I wanted to explore, to put Grace in a situation where her second husband didn’t allow her to grief.

You’re also intrigued by mental illnesses, can you elaborate?

Mental illness is related to grief in a way that it’s also an inappropriate emotion. What I wanted to do with Ghosting was explore the whole women-madness thing. It has been, and probably still is, a way of controlling female behavior. Asylums are places of containment for people, and quite often women, who are not acting appropriately. I have spent the last 20 years reading texts, novels, and poetry that center on the issue of female madness so I wanted to weave the subject into the book.

Do you think this book will attract a different audience than for example London Triptych?

I didn’t aim for any audience with any book really, other than attracting people who might be interested in the subject matter, the stories. I’m very pleased that London Triptych had a wider appeal; my mother and a lot of her friends really loved it and when I won the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award, there were much older women congratulating me because they really wanted that book to win, “Because it’s filthy.” Ghosting had some great reviews and maybe that’s because of the way in which it’s so different from my previous work. It didn’t had the impact that London Triptych had, but that probably had to do with its slightly sensational subject matter and the explicit sex scenes. London Triptych is massively important to me because it shone a light on something that was marginalized: the history of male prostitution. It became a kind of stock novel for queer culture and queer history in London, which is great. It’s wonderful when a novel can have such an impact and is not just a flash in the pan. Ghosting is a much quieter book, yet it seems to have appealed to new readers. I’m grateful that they enjoy what I’m doing but I never really think about a specific audience and I certainly didn’t think it wasn’t for my ‘LGBT audience’. Primarily I will always write about LGBT lives, because that’s the life I live, and the world I inhabit, and as a writer you do draw of your own experiences. The way in which sexuality is dealt with, both historically and currently, in society has always been of interest to me so I will continually explore these issues in some shape or form.

Next to being a writer you also teach creative writing and comparative literature at Birbeck College, University of London. Do you like it? I do. I love the contact with my students and the whole experience of being in a classroom. The difficult part however is the marking, because you have to sit in judgment about the work of people you really like and in creative writing there is, obviously, a huge subjective element to it. Luckily there are criteria that you have to work with and even if you don’t like what you’re reading, you try to see the merits of it. I never imagined myself as a teacher though. I was always so desperately shy about talking in front of a group of people but I found that I really liked it. I was relieved to be good at something that actually made some money (laughs).

‘Primarily I will always write about LGBT lives, because that’s the life I live, and the world I inhabit, and as a writer you do draw of your own experiences.’

I once read an interview with Paul Auster in which he stated that he could tell when a writer had followed a creative writing course. Do you agree?

The whole industry of creative writing has been going on much longer in America than in the UK, but I’d agree with Auster on that one. Luckily you still get enough books that are maverick, written by somebody who has not allowed it to characterize their writing.

You think there’s an actual formula for a bestseller?

I do believe there is a formula, yes. I’m teaching a course at the moment about genres and analyzing the narrative structures of them. I think a formula is actually something that provides a pleasure to readers who would be disappointed otherwise. In a thriller, for example, you expect a certain unease; there’s a body and you have to solve the crime. You cannot, not solve the crime. You find a good metaphor for a reader/writer relationship-gone-wrong in Misery by Stephen King where the reader cripples the author when he does something she doesn’t like. Arthur Conan Doyle got bored with Holmes and killed him off in order to be able to write something else, but his readers became furious and demanded he bring Holmes did; so he did. He almost had no choice. The other things he wrote and published didn’t sell in the same amount so he was kind of coerced into resurrecting his most famous character. As a writer you obviously have some rules of commitment.

Do you have to write? Is it an urge?

I’ve been writing all my life and my first novel only got published when I was in my early 40’s, so I always had that compulsion to write. I have always had the compulsion to read too, and for me the two go hand in hand. I don’t feel driven in as much as expressing something that ‘has to come out’. I’m driven to explore things that I’m thinking about, or images and characters that appear and who need to be observed.

How do you write?

I’m not sitting down and tapping away my random thoughts; it’s usually a story that I want to tell, need to tell. I don’t know where the ideas come from; they just pop into my head. I work really slowly and I like to rework a text quite a lot. Ghosting got re-edited, re-drafted, probably over 20 times. The first draft I wrote was in the first person, in Grace’s voice, or an attempt at Grace’s voice, but it didn’t work. While I was figuring out why it wasn’t working, I came up with the idea of changing the point of view. I tried it out on the first couple of chapters and immediately the prose came alive. It wasn’t simply a case of replacing ‘I’ with ‘her’ or ‘she’, but something entirely different had to happen with each sentence once the point of view was shifted.

You’re quite an activist on the internet, is writing also an attempt to change the world?

I wouldn’t call that activism. That’s a big claim for any writer to take. Books don’t really change the world but they can change people and people can change the world. When my PhD, The Penetrated Male, came out, I talked about it at an event in a room filled with people from different sexualities and different genders. They were all talking about something because I’ve written a book about it. It was amazing because how often do you really have a serious, large scale conversation about men being penetrated?

Related articles

Bernard Perlin

Annelies Verbeke

That’s a tough one because I don’t like to be put into a box. For me, Thirty Days is just a continuation of everything I’ve written before. I’m working on an oeuvre, which I started in 2003, and hopefully will be able to build up till the end of my days…..

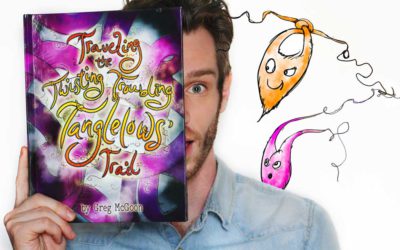

Greg McGoon

Author and theatre performer Greg McGoon challenges the norm of children’s literature. By choosing a transgender princess as main character of the fairytale The Royal Heart and teaching self-acceptance in The Tanglelows, McGoon tries to…..

Ivan E. Coyote

On the day of this interview, New York passed a civil rights law that requires all single-users restrooms to be gender neutral. A decision of great impact on the daily reality of trans people and a life-changing event for Ivan E. Coyote. The award-winning…..

Square Zair Pair

Square Zair Pair is an LGBT themed children’s book about celebrating the diversity of couples in a community. The story takes place in the magical land of Hanamandoo, a place where square and round Zairs live. Zairs do all things in pairs, one…..

Ghosting. A novel by Jonathan Kemp

When 64-year-old Grace Wellbeck thinks she sees the ghost of her first husband, she fears for her sanity and worries that she’s having another breakdown. Long-buried memories come back thick and fast: from the fairground thrills of 1950s Blackpool…..

Leaving Normal

Leaving Normal: Adventures in Gender is creative nonfiction that takes an unflinching but humorous look at living as a butch woman in a pink/blue, boy-girl, M/F world. A perfect read for anyone who has ever felt different, especially those who…..

Amanda Filipacchi

I was 20 when I read Nude Men and I instantly got hooked on the surreal imagination of this New York based writer. 21 years and 3 novels later there is The Unfortunate Importance of Beauty, and Filipacchi hasn’t lost an inch of her wit and dreamlike tale…..

Gay & Night

Gay&Night Magazine started off in 1997 as a one-time special during Amsterdam Gay Pride. It soon however became so popular that it evolved into a monthly glossy. Distributed for free at almost all gay meeting spots in Belgium and The…..

Bart Moeyaert

Bart Moeyaert is internationally famous for his work as a poet, a writer, a translator, a lecturer and a screen writer. He once mentioned on television (on ‘Reyers Late’) that society is often overwhelming, that one is alone with one’s thoughts about…..

Jonathan Kemp

Jonathan Kemp won two awards and was shortlisted twice for his debut London Triptych. Gay bookstore Het Verschil in Antwerp, asked to interview the British author for a live audience due to the Dutch translation of his novel, ‘Olie op doek’. A…..

Michael Cunningham

We meet Michael Cunningham in Brussels where he is invited as an Artist in Residence by literary organisation Het Beschrijf. Coffee, Belgian chocolates and a conversation with the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Hours……