Geen Resultaten Gevonden

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text JF. Pierets Photos Frank Clauwers

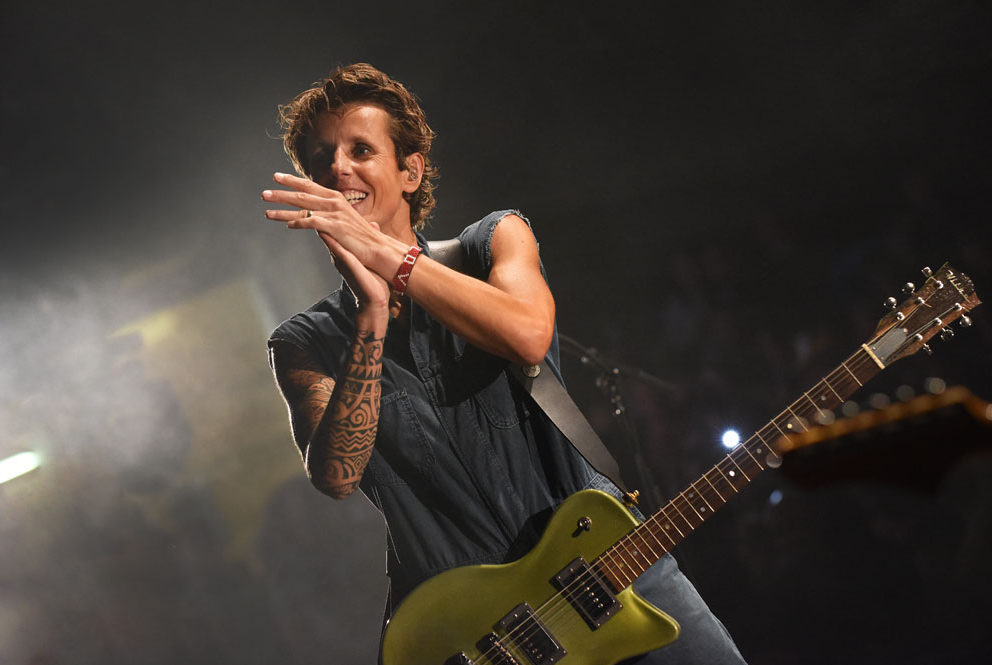

I’ve always been very much intrigued by Sarah Bettens. When I saw K’s Choice perform in 1994 they had not yet recorded their monster hit “Not an Addict”, which opened doors not only in Europe but also lead to touring across the US with, amongst others, Alanis Morissette and the Indigo Girls. Yet in 1994 I saw a girl run to her microphone, hold onto it for the entire song and who looked at her feet for the duration of the applause. A lot has changed since then and that girl cannot be compared to the über-fit and charismatic front woman she is today. We catch up in the backstage area of a Dutch music festival to talk about change, identity and challenges.

You once said you were lucky K’s Choice became popular. What’s luck got to do with it?

I think there was a lot of coincidence involved. My brother and I have been making music for as long as I can remember but we never thought about it as a future job. The idea itself was even too unrealistic to dream about, so let’s just say we never considered it a possibility.Then someone asked me to sing something in a studio and before we knew it we had a hit-single on the radio and things started evolving. There wasn’t any plan behind it. If I contemplate our position right now, I can see the amount of work and effort that we have put into it, yet I must say that we did indeed get very lucky. We met the right people at the right time. Of course you have to be present in order for those people to find you, but we were very lucky to kick off mid-’90’s, when record companies still had a lot of money and room for development. We’re talking about a completely different era here. They allowed us time to grow, which is almost impossible nowadays. We’re also lucky that we’re still – after 25 years – able to make music for a living. We still have fun and we’re still doing things that challenge us, both as musicians and performers. There’s nothing worse for creativity than routine so once in a while we have to shake things up a bit.

How do you shake things up?

Well, for example we changed our working method when making The Phantom Cowboy – our last record. Normally Gert and I write separately and then bring things together to see what happens. This time we started with a concept and actually knew how we wanted the record to sound. Things like this, and also things like introducing The Backpack Sessions – an intimate tour with only our pianist – are our means to keeping it fresh.

Do you need challenges?

I think so, I’m not a stressed out person but I like change, both in my job and in my personal life.

At the moment we’re on the verge of moving to California and there’s a lot to do, but that’s fun. We’re going to start over. It’s like making a new record and working with a new producer, even though the previous one was great, you never know what it’s going to bring. My sense of adventure is far greater than being comforted by foreseeing the future.

A couple of years ago you started working as a fire fighter? Why?

I needed it because music started to become somewhat of a routine. I needed to do something that was completely different, a job where I had to show up and go back home after 24 hours. As a musician you can start working at 2 in the afternoon or you can work the whole night through. You work on your music, your plans, your career, your writing, you name it. It never stops. You can work all day and there will still be that feeling that you can do more. It’s never finished. So I looked for something that was defined, which I found in being a fire fighter. You cannot imagine how much I learned there and it still brought me the eagerness to learn even more. Because of that, being a musician made me happier again.

Do you have any creative rituals when you start composing?

We did in the beginning, but I’ve kind of abandoned the idea of needing hours of time, the right mood and even the perfect star constellation – in order to write the perfect song. Now we just sit down with a guitar and start. The Phantom Cowboy was written in two weeks time. Gert and I sat down in a room from 9 to 5 and just worked. We stopped waiting for the right light interval or the most opportune emotional state of mind.

Is art inevitably self-portraiture?

I think so. You keep talking about things that are close to you. Its shape changes but the subject doesn’t. As you get older your world changes, you get married, have children, yet there are themes that keep returning. Now we’re moving I found some old interview from when I was 20 years old. How stupid and serious I was! Nowadays I take my music, my job, very seriously but not myself. Now we’re able to write a song that’s ‘just fun’, it doesn’t always have to be about the most deep down, thorough, detailed emotion. At this point we’re able to lighten up.

You are outspoken about being gay. Do you feel you have a moral responsibility?

I do like taking my moral responsibility. I like it that young girls or boys can look at me and know that I’m married to a woman and yet look very normal. When I was young I only had Navratilova, and even she was not very outspoken. The issue just wasn’t discussed. It took me so long to discover who I was and I think that if I was born now, I might’ve found that out by the time I was 16. There are so many possibilities now, people can talk about being gay, being transgender. Things that weren’t discussable twenty years ago. Of course there’s still a lot of work to be done, but as a public person I hope to make the world just that little bit more normal for gay people. Writing and making music is a very nice way to communicate with people and to discover that you have much more in common than you would think. When you’re a teenager that can be quite therapeutic.

Jeff Koons once said: ‘Being an artist is not a job, it’s an identity’.

I think I rather identify myself as the wife of my wife, the mother of my children and the daughter of my parents, my friends, than as an artist. Don’t get me wrong, music is a great platform and making music is something that can’t be compared to many things. When you leave the studio at night and you’ve created something you didn’t know existed that very morning, it’s incomparable. That little bit of fear, that you’re never going to be able to do it anymore, or the feeling that you’ve given everything but aren’t sure if there’s anything left. I have to admit that’s a unique and an on top of the world feeling. But to say it’s an identity, that’s too much. I identify much more as a human being than as a musician.

You and your wife adopted 2 children a few years ago. As a mother, what would you like to teach them?

I want them to be able to be themselves. The world won’t always appreciate or understand that, but at least they have to try. I also want them to work hard. I enjoy my life very much because I work hard for the things that I find important; to be happy, to do things with my family. If you feel very good about something, then it’s often something that took a while for you to get there. For me, getting divorced wasn’t an easy road to take, nor was adoption or moving to the States. But they did make me happy in the long run. I feel very strongly that I’m the happy person I am today, because of all the decisions I have made in my life. I’m very grateful about the circumstances and being lucky at the same time, but I also made it happen through the choices that I made along the way. Next to getting sick or loosing somebody, your fate lies very much in your own hands. So how committed are you to work for it?

So in retrospect, you wouldn’t change anything?

I’ve gone through some painful stages yet I’m very happy with who I am right now. Everything that’s happened has made me into the person I am today. Fortunately I’m quite forgetful so that might help (laughs). I can’t imagine anything more drastic than what happened to me when I met my wife. Before that I wasn’t really happy but I thought that was just the way people were. When I found out who I was I literally stepped from a world of darkness into the light. All was black and white and I changed from being – I’m not saying depressed because that’s too strong of an emotion – but from heavy hearted and melancholic to one of the most joyous people I know. Almost in the blink of an eye.

A question I also ask myself: How could you not have known?

I have absolutely no idea. Maybe it has to do with the era in which I was born. I think that if I would be 16 years old at this very moment, I would probably jump right in. In retrospect I conformed a great deal. Especially because I wanted to dress like a boy but I didn’t want to embarrass the people around me. If it would only have been about me, than there would’ve been no boundaries. I always had to fight for my place in high school, something you don’t quite understand when you’re so young. That’s what I like so much about the whole gender conversation. Who cares about all that? You could say that it’s safe to fit in, but is it really? How many people are there that get a wake-up call when they’re 30. I’m longing for a world where everybody can be more relaxed into doing what they want to do. Everything feels so restricted.

What do you think is your purpose in life?

It depends on when you ask the question. Sometimes you feel so small wondering what’s your part in this larger entity. When you dare to think about the concept of time, the universe, or the fact that we are standing on something circular, then it’s almost impossible to ponder the meaning of your own life. Everything is so grand and you are so small in comparison.Yet when I do have to answer on the meaning of ‘my’ life, I think it’s trying to change and affect the world around me by being happy and treating people with respect. I’m a bit too cynical to be able to positively say it’s going to change the world, but it would be a good start. When I hear those terrible stories about sick children or refugee children, things that neither you or anybody else can fix, I often reflect that being grateful about the things you have and are able to do, is the very least you can do. Trying to give as little thought as possible to the small things that bother you. So every morning when I wake up I keep my eyes closed and think about the things I’m grateful for. That’s the absolute minimum you can do when you see all the damage that’s been done in the world. If everybody would make the effort to change his own little corner in a positive way, it would already mean a lot.

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text JF. Pierets Photos Wonge Bergmann & Sam De Mol © Troubleyn / Jan Fabre

It took more than one year for Jeroen Olyslaegers to write the text for Jan Fabre’s 24-hour theatrical performance Mount Olympus, to glorify the cult of tragedy. A labyrinth of time where the actors sleep and awaken on stage, dance and move in the violent, ecstatic proximity of characters from Greek tragedy. One night in Seville Julian and I watched history in the making and we were in awe during every minute of it. A mind-blowing and life changing experience that made us realize that you hardly ever get to experience and recognize a masterpiece in contemporary time. In conversation with Jeroen Olyslaegers. About stripping down emotion, writing at the very top of your abilities and the meaning of life.

How does one start such a huge project?

The first thing I did was reread all 32 Greek tragedies. I got inspired and then buried them. One year later, in June 2014, we started rehearsals. Since it was impossible to write the text beforehand and give the actors a syllabus of 200 pages – everybody would get a panic attack – I wrote during rehearsals. I reinvented and introduced my own themes by using the original material in a new way. There is not one sample of the original texts in any of the monologues, yet some of it is pretty close to the principal characters.

You not only worked, but also slept within the proximity of the rehearsal room.

That was my one condition when I accepted Jan’s offer. I wanted to be close to the rehearsal room because the performance is about dreams, about problems with sleeping, so it was clear that my own situation was going to be very influential. Rehearsing and writing Mount Olympus was like a marine boot camp where your head get’s to an amazingly trained level. When I had been writing for half a year, I felt like a Lamborghini. To give you an example: in October I needed two or three hours to write a monologue, in March I needed fifteen minutes to write the same piece in both in English and in Dutch. You are inside this Greek monster and you know which way to go. Like a racing car driver who knows every turn of the circuit. As a writer it was a unique position to be in and a once in a lifetime experience. Who would do a 24 hour performance after this? It’s almost impossible.

It’s quite the tour de force to comprehend 24 hours of text and images. How do you tackle such an overpowering quantity of material?

One of the things we discussed a lot was if we needed to contextualize the characters. Do we need to explain to the audience who Medea, or Dionysos is? We decided to try but it soon turned out to be completely stupid. We had to get rid of the hang-up that the audience needed a context, needed to know about Greek culture and ancient tragedies in order to be able to enjoy the performance. For us, it was tabula rasa. But the moment we knew the people did’t need this cultural baggage, it was a breakthrough. Another turning point was the moment Jan challenged/ composed the first and the final part, which was the first thing that came together. You have to realize that for every scene that you see, we had four other scenes so we’re literally talking about thousands of scenes, all with their own small or larger variations. Assembling such a volume of material is madness, yet when we all saw a sketch of the first and the final part, we suddenly had a clear sense of direction. We suddenly knew we could do this.

It’s not the first time you have worked with Jan Fabre.

Five years ago we made Prometheus together. Working with Jan it so intense that it’s incomparable to any other director. Jan puts you on the edge of a cliff and gives you a push. You fall, that’s it. For one year we worked on a level where none of us was convinced that we were going to make it. I remember the first time we tried out the complete 24 hours; we started out at 5 PM, the sun was still shining, and at 8 in the morning we said to each other, “what are we doing? This is crazy!”.

You write novels, which is a very solitary profession. How does it feel to co-create?

I love both. A combination of solitude and collaboration. The interaction with a group also feels fantastic. You get totally different ideas and I feel I’m becoming a better artist when I work with other people. Of course there are some conditions like having the same focus and the same intensity. Let’s say Mount Olympus made it impossible to work on a theatre project with no intensity.

Did you have faith in the outcome?

We were worried about the performers who had to give every inch for the entire 24 hours. They have to be in control of their bodies. We were worried that they would hurt themselves due to sheer tiredness because people react totally differently when they lack sleep. And to handle that tiredness is different for everybody. Some need 45 minutes, others need 3 hours, and some of them don’t want to sleep at all. At every point of the process we didn’t know what was going to happen next. I had no idea that Jan was going to rehearse the entire piece in every detail, which was totally crazy. For me it’s still a miracle that everything you see has been rehearsed over and over again. If somebody jumps from a table, it’s rehearsed to happen exactly at that moment. There is absolutely no improvisation. Can you imagine the amount of time you need to write and direct 24 hours of performance to the smallest detail? It’s almost impossible. How do you cope on a mental level? The performers rehearsed so much and for such a long time, that they found themselves in a dream state where they could do almost anything.

I guess Mount Olympus was quite up your alley because of your fascination for the concept ‘time’.

Afterwards it’s weird to reflect on what we did with time. For me time is linked with catharsis; we have this old 19th century idea of theatre. We expect to look at a play, in a dark room filled with other people and expect a catharsis. For me it’s a strange idea to expect an insight from a 2 or 3-hour play. What actually happened in ancient Greece were these big Dionysian festivals, competitions between different playwrights. People came to the theatre at dawn and watched for about 12 hours. They had dinner, had a drink, it was a coming and going and the catharsis was the entire experience. That’s what we do with Mount Olympus. We actually stretch time, where the catharsis is totally different and much more violent for the audience to capture. After a couple of hours we strip away the intellectual human layer and what remains is pure emotion. It’s not uncommon that people start to cry because there’s no protection left. We’ve demolished it. That’s the Dionysian power of it. I actually have Dionysus say this in the beginning of the piece; “we’re all going to get you really, really crazy. We’re going to get you mad”. Which is what happens at the end.

And every time the performance gets a standing ovation for more than half an hour.

We never had a Mount Olympus performance where the audience was not connected. Putting more than a year’s work into a project, makes the love you get in return very intense, very moving. The level is magic. We wanted that, but we had no idea it was going to be this euphoric.

Mount Olympus is a statement against the pressure to produce quick and cheap entertainment. Has this experience changed your own way of creating?

It taught me to go to the essence, to not be afraid of using emotions – even when they’re strong and hard – and to get rid of the last reminisce of irony that I had. I still like a good joke and I like sarcasm but for me, writing is for real. As a writer I want to kick you in the heart and in the head. Mount Olympus has taught me to become much more intense. Intensity is everything. You have to go for it and not wait anymore. What I feel now in a very urgent way, is something that’s happening to the world at this point.

The performance is a political metaphor for society now and back then.

Mount Olympus starts with two guards, blowing a message in the ass of another and talking about an ecological nightmare and the apocalypse, which sets the political tone of the entire piece. It’s about war and the way we tend to fuck up our karma by breathing hate the entire time. Every Greek play is only about one thing; there’s a bill to be paid and somebody has to pay it. I connected this to the tragic times we now live in. Think about King Oedipus; because he killed his father and married his mother, a plague broke out in Thebes. But he doesn’t know that. He asks people to check why there is a plague. They all return saying that he is the reason but he doesn’t believe them, he just keeps sending people to go and check. This is what’s happening today also. Ecologically we’re on the brink of a big disaster and we’re going to have to change our lives to pay the bill. That’s what Mount Olympus is about: there is something that has to be reckoned with.

Are you saying that nothing has changed?

I think blindness has increased. We no longer have the confrontational insight of Greek tragedy. People think that theatre is entertainment, I think theatre is drugs. It’s an attack to your system, an attempt to transform you.

If it’s not entertainment than it’s activism.

Definitely. For me art has to be activism, otherwise it doesn’t work. For other artists it can be a quest of beauty, but for me it’s a tool to activate people. And that’s what we did with Mount Olympus. If you look at Jan’s theatre plays you see that they are always based on provocation. To wake you up. And sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, yet you feel that there is this activating principle. I think that’s why we’re friends, we understand each other on that level.

I once heard you say that Greek mythology is your spiritual landscape. Can you elaborate?

My spiritual landscape corresponds to the Greek, but also the Celtic times before Christianity. It’s a very creative time. You have monotheism – which I find very boring because it’s like a block of concrete, and you have polytheism, which is very liberating and why I call myself a Satyr. There’s this great sense of play. Context is everything in Greek mythology. It’s like quantum mechanics but based on mythological thinking. What I think and what I do is invest time into taking these gods seriously. Trying to give them a place in my work – like Mount Olympus, but also in my daily and practical life. I think the Greek gods are not dead, they are among us. It’s a totally different way of looking at spirituality and religion. Especially now, when every religion is becoming dogmatic again, we need some liberation by introducing play.

What do you do to tap into your creativity?

I do something physical. I walk, or go for a swim. It used to be just reading but now it’s much more listening to nature and going out. Everything that I see is a gift that I can use, so there is no coincidence in my life. The great thing about writing is that it enhances your feeling of observation. When you write a novel, you have this mental space where the novel lies. I’ve just finished a novel about Antwerp during WW II, and I have this specific image of the city in my head. I know how the streets used to look 70 years ago so I can walk through Antwerp by just closing my eyes. I also go to that place to meditate. I can sit in a bar, have a coffee and be in 1942. I go to that mental space to solve plot problems but also to chill. And it becomes more relaxed when you’re on a bike or on a walk.

What do you hope to be your lasting significance as an artist and a human being?

Those two things are very combined now. I used to be just a writer, but now activism has mixed everything together. It’s a difficult question. I think I want to leave this lasting impression of love for humankind. Everything that I currently do is situated on what the Indians call the heart chakra, both in and outside my writing. I want to link people to each other because basically I think we need to invent a spirituality that connects people to each other. Whether you’re Muslim, or Jewish, or an atheist. Like Moses, we can use two stone tablets with one sentence carved onto each one of them. The first is “we’re all one”, which was proven by genetic science 50 years ago, and the other one is “we all share the same planet”. The way we live needs to reinvest respect for the planet, consider her as a mother instead of something that we exploit. I’m always trying to combine these things in my work because there’s a sense of urgency to act. That kind of energy is the lasting impression I would like to leave behind.

I read this beautiful quote by Viktor Frankl, stating that “Ultimately man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked”. Any thoughts?

It also means “know thy self” and it is one of the most difficult questions there is. But also the most beautiful. “To become what you want to become in life is the most difficult thing ever” is one of the sentences that I use in my new novel. It’s the most difficult and at the same time the most provocative thing to do. Because the majority seem to want you to remain not who you are, but who they all are. Being like everybody else. Yet everybody has the capacity to fly and the capacity to become who you think you want to become. It can take your entire life to get there, but that’s the spiritual beauty of the whole thing. If everybody does this, focuses on that, or if we have this critical minority who’s focused on that, the world would be a better and more interesting place. And I must say that it becomes easier with time. The older you get the more you realize that what happens in your life are actually forces, pushing you to your destiny. I have this big storytelling tradition in my family but I started out as a post-modernist writer and an intellectual deconstructivist. Now I’m liberating myself with every book and every theatre play to get closer and closer to what I’m trying to become and what I am destined to be; a pure storyteller.

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text JF. Pierets Photos Daggi Binder

Ever since the beginning of Et Alors? Magazine we have had a soft spot for singer, model, bon vivant and muse Le Pustra. Being inspired by the same artists and artwork such as the Oskar Schlemmer’s costumes for the Bauhaus movement, Georges Méliès, Klaus Nomi and Leigh Bowery, we always make sure to keep in touch with his work in progress and latest endeavors. Leave your inhibitions at the door and say welcome to Le Pustra’s Kabarett der Namenlosen.

It’s the first time I’ve seen you without make-up, which is quite weird, but I guess you get that a lot.

All the time. I guess when people see the make-up, they don’t ponder on the fact that it’s not real. Like they expect to see me in white make-up all the time. It’s quite interesting really because it’s the same thing with movie stars where people fall in love with the image. The reality is quite different though.

In reality you’re a different person to the one you are on stage?

The last 4 or 5 years it’s definitely ‘me’ but with make-up on. In the beginning it was more a character as such. More exaggerated. I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do and who I wanted to be. Time brought me more confidence and I’m more relaxed now, yet I’m not one of those performers who have to be on stage all the time. I’m very happy to be natural, at home and be quiet. For me it’s not a lifestyle.

Tell me about your new project.

In 2012 I went on a Christopher Isherwood-tour through Schöneberg, Berlin. He went there in 1929 and wrote Goodbye to Berlin in 1939. During the tour, the guide mentioned the Kabarett der Namenlosen – the Cabaret of the Nameless – and it intrigued me very much. Little information is available but this Cabaret existed from 1926 till 1933. It was one of the most disreputable yet very successful shows because the host, Erich ‘Elow’ Lowinsky, would put talentless or disabled performers on stage just so the audience could make fun of them. It was a bit like today’s talent shows where people let themselves be humiliated on TV, just because they want to be famous. When I read the story of the Kabarett it was not exactly what I wanted to do, but I really liked the title as such.

You moved from London to Berlin. Why there?

It’s difficult producing new shows in London nowadays. The scene is so oversaturated and there’s too much happening all the time that people get bored. So it’s really a struggle to get people’s attention, and if you do it’s very fleeting. When I ended up in Berlin last year it all came together. I contacted Else Edelstahl from Bohème Sauvage – Berlin’s biggest 1920 party concept for over ten years now – pitched my idea and she was interested. Plus we found a beautiful venue called Ballhaus Berlin, a gorgeous building from 1905 and an original ballroom from the ’20’s, so it all sort of came together very easily. The city is having its moment in the spotlight and if you are very motivated it’s a perfect place to create something. All the opportunities are there.

Tell me about your fascination for the ’20’s?

Coming out of the restrictive and repressed Victorian/Edwardian period and then the First World War, it must have been an exhilarating, liberal time. Especially for homosexual men – who were finally able to have easier access to gay sex. Berlin suddenly became this Sodom and Gomorra where you could live out every filthy fantasy that you ever had. In contained spaces that is. But the reality was that Berlin was gripped in poverty and struggle. We tend to only focus on the glamourous side of the ‘Golden Twenties’ in Berlin but cabaret was mostly enjoyed by the privileged and the rich. I think we all have different ideals and fantasies of different times. We may fantasize about the ’60’s or ’70’s for example. For me, this show is my fantasy of the 1920’s. It’s what I envision. I wanted to present it in a fresh way by mixing a lot of contemporary music and live original ’20’s songs with a lot of dark undertones. I really took all my inspirations including fashion, film, music, and put it all together. And it worked. The show really transports you back to that thrilling and interesting time.

This show is a stepping-stone to you becoming more and more of a producer?

More than anything it was a personal challenge. For the last 10 years I’ve performed in other people’s shows, therefor you’re never really in control of the environment. Promoters cast you as one of your personas but the setting is not your own world and a 5-minute performance is not that satisfying, not to me anyway. I’ve changed a lot over the years and I want to establish myself as a producer and a creative director. Basically it’s about using all the experience I’ve gained which – I’ve been lucky – are many different skills. For me it’s the perfect time to move on to the next step and create something that satisfies me. This show has given me a lot of opportunity to blosom into something new. To keep evolving and reinventing myself. Like Madonna.

The show is a success, I guess that makes you proud?

First and foremost it was a validation. You always have to prove yourself and as an artist there’s always this doubt that never goes away. So the result was good and it showed me that you can do a lot of things if only you believe in yourself. I know this sounds cheesy but it really did affirm my abilities. You don’t know if it’s going to succeed. There are no guarantees with artistic endeavors. I wanted to put great performers like Bridge Markland, Lada Redstar and Reverso – who possibly wouldn’t normally collaborate – together. It’s a mixture of disciplines, aesthetics and oh a lot of nudity. Naturally.

Why naturally?

The nudity is not presented in a sleazy way, it’s part of the whole experience. After a while you just don’t even notice it anymore. In a lot of productions nudity feels so sanitized nowadays, so I wanted to see how far I could go. It’s not a question of trying to be provocative, it’s just an essential part of Berlin Cabarets from the Weimar-era, to which I’m staying as true as i can. In Kabarett, the performances are happening around the audience, the spectator is part of my darkly twisted and sexy little world. They are transported back into a Weimar ‘nachtlokal’ and my intention is to have the audience forgetting where they are by creating a disorientating smoke bubble and moving art. It’s not a traditional Cabaret but a complete theatrical experience and the moment you walk in, it’s already happening.

What are you plans for the show?

I want to establish it in Berlin as a main theatre show. Tourists go to Berlin in search of the movie Cabaret but are unable to find it. You’d be amazed to see how many people are actually searching the Internet to see where Sally Bowles performs, while she doesn’t even exist. Now it’s quite interesting that an Ausländer – which I am – has created this vision. A lot of Germans don’t have a clue of their city’s rich and naughty Cabaret history. I think the fact that I have a direct link to the grandchildren of ‘Elow’ who created the original cabaret – his granddaughter found me on the Internet – makes me a good candidate to keep this piece of history alive. Since we tend to romanticize this period I wanted to make my show a ‘surreal version of what i want it to be’. I’m also producing a Revue version of the show, with myself and my fabulous pianist, Charly Voodoo, which can tour anywhere. And the third idea is to offer Kabarett as the ulitmate luxury show for private events and clients thus making the show versatile and creating more job opportunities in the process.

Aiming big. I like that.

If you really believe in your vision and are focused, something good ought to come out of it. If you compromise too much it translates and the end result becomes sloppy. I think I’m confident enough now not to compromise anymore. It’s a hard thing to do for a lot of performers because you are scared you won’t get booked again but you need to find a balance between being very assertive in what you do and being able to communicate this in a polite and professional way. But you need the confidence to say no. Artists will always be challenged and I sometimes wonder why I have all these talents and can’t make a living out of it. But I’ve accepted that this is who I am and just get on with it. I feel I’ve come too far now to stop and you never know when your big break will come. From this moment on I just want to enjoy what I’m doing. And if it pays the rent, then that’s great. There was a time when I wanted fame, now it’s not my priority anymore.

If it’s not fame, then what is it?

I think you can call it destiny. This is what I’m supposed to do. It’s as simple as that. It’s just who I am and I know that if I would stop, I would be very unhappy. It’s something that’s part of you and I’ve accepted that. Sometimes it can be pretty scary because as an artist there are no guarantees, you’re constantly stressed about money, and then there’s this whole issue about being validated. But I’ve accepted this and have completely surrendered to it. Once you get over it, you can get on with the more important things.

Tickets via www.boheme-sauvage.net

www.kabarettdernamenlosen.com

www.lepustra.com

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text JF. Pierets Photos Amanda Arkansassy Harris

“If you don’t see femmes as queers, it’s because you choose to not see us. You are invested in our erasure. We are here. We have always been here.” A strong quote, coming from Dulce Garcia, AKA Fierce Femme, one of the participants in Femme Space, a photo project exploring queerfemme identity and reclamations of space through portraiture. Queer femmes of all genders choose locations to reclaim sites of marginalization, erasure and invisibility. A conversation with co-conspirator and photographer Amanda Arkansassy Harris.

Can you give me your personal definition of ‘femme’?

I have thought about that since my mother first tried to wrap her head around me. It’s difficult to explain. It’s feminine and it’s queer and it’s different from straight femininity. My mother asked if femmes shaved their legs, which is actually an important question because some do and some don’t, so I think that’s really illustrative that you can’t define queer femme. When you’re in a community of queer femmes you feel what it is, you feel part of a tribe. But I cannot put an exact definition to it.

You identify as queer femme, so is this a personal project?

Definitely. I’ve had many experiences where my femme identity was either invisible, erased or attacked. Speaking with other femmes, I’ve learned that my experiences aren’t isolated to me, and in fact femmes of all different backgrounds experience marginalization daily. So this project is personal, political and an act of solidarity with femme community.I think there’s something about collaborating with another femme that feels safe. We’re going back to locations where they have experienced daily harassment or judgment,so having another femme there with you to have your back, is a very empowering experience. Plus, I have seen many masculine photo series centered on butch identities and thought we needed to add more femme faces and voices to media.

You talk about reclamation of space. Reclamation as in ‘winning back’?

Reclamation is taking it back for yourself or owning it in a way you didn’t get to own it before. Queer feminine people do not often get to navigate the world in ways that feel good to us or authentic to our experience. This project is about getting to do something on our own terms and to be seen, as we want to be seen.

You thought it important to accompany each picture with the model’s story.

There are a lot of photo projects out there that don’t use any narrative so what I didn’t want was just to have images without the femmes being able to use their own words. Some images have a lot of strength but I find there’s also a great deal of assumption. Femmes already live in a space where they have assumptions made about them all the time, so it’s about getting to say what they want and on their own terms. I wanted to avoid having people trying to guess who they are and how that experience was for them.

You say Femme Space exists to draw attention to the experiences of queer femmes and to amplify those stories in art and media. Are you aiming for a mainstream audience?

A mainstream audience is a secondary audience for me, with Queer community being the primary audience. If part of the mainstream can look at our stories and really see us, then that’s great. Yet if they can’t, we are doing the storytelling primarily in queer community, which is also fine by me. I want to elevate those stories to whoever can hear them.

You are taking the word “queer” as a political identity. Can you elaborate?

Queer is a great catch all term, but indeed I see it as a political identity. For me it’s about not assimilating: not trying to be like straight people or live our lives based on heteronormative values, but to really set our own standards and values that aren’t mirrors of what straight people think we should be. Classic example questions of this are “should we be fighting for gay marriage?” Are we trying to get the same things as straight people, or do we want to set our own terms of what relationships should look like? To me that’s a very queer issue, and I do consider myself queer because of the way that I view the world. My art is queer activism. Curating is activism, because it’s about trying to bring as many people to the table as you can to tell a larger story.

I guess such an involvement doesn’t happen overnight?

Not at all. I grew up in a rural town with one stoplight in the south in Arkansas. I always felt a little bit different and couldn’t quite place what that was. I didn’t know that it was queerness at the time, but I didn’t see myself fully reflected in the people around me. I’ve always been a writer, always making things. Once I came out as queer I got involved in an organization in Arkansas that uses art for social change, Center for Artistic Revolution. And I saw the power of that: the power of artists creating art to make change, the introspective process and how people responded to it. From portrait photography to holding a sign on a street corner, art stops people in their tracks to have a conversation with you. I was in my 20’s when I saw the power art has to tell stories and I’ve been pursuing it ever since. I’m really fortunate to live in San Francisco where you can get small amounts of arts funding to dream up these projects.

Tell me about your plans with the Femme Space project?

The Femme Space project is still unfolding itself to me and I’m trying to be really patient with that. I’ve been trying to digest the femmes who are coming to me – telling me what the project means to them – and thinking about where I would like that to go in the future. I have a form on my website for people who want to participate and I’ve received responses from Germany, the UK, Taiwan, all over the world. So if these femmes see value in this project and they want to participate, then maybe I need to go to them. But what I definitely want for a project like this is for it to be considered as radical, revolutionary and important. These are stories that need to be told.

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.