Artist Ayakamay explores the interrelationship between photography and performance. She simultaneously appropriates traditional Japanese cultural aesthetics and creates a dialogue with contemporary American urbanity and femininity…..

Heather Cassils

Heather Cassils

Text JF. Pierets

Cassils first caught our eye in the ‘Telephone’ video, where the performance artist and personal trainer made out with Lady Gaga in the prison yard. Intrigued about this appearance, we discovered a highly intelligent artist who pushes the boundaries of the body while making statements on today’s perception of the image. Creating a visual language that uses the physical body as sculptural mass, Cassils turns exercise into a metaphor for a society that is obsessed with consumption and surface.

Can you tell me about your art?

I used to paint and draw a lot when I was a child. I remember that when I was 6 years old, I won a drawing competition. I always was a bit of a weird kid and I think that was the first time I have ever been acknowledged. Although I work with the body now, I was always a kind of secret painter. And I do watercolours, but don’t tell anyone!

Why did you start working with your body?

I started making art with my body for different reasons. Partially it was due to education. When I was 20, I worked for The Franklin Furnace, NYC’s largest non-profit organisation dedicated to performance art. Here I was hugely exposed to epic body based performances that they housed in their archives. I went to Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, an art school in Canada heavily influenced by 70’s conceptualism and I got my masters from California Institute of the Arts, where I read a lot of Marxist theory and learned about institutional critique from Michael Asher, who remains to this day, a big influence. I also came to my body through an illness I survived as a child. It sounds rather benign but it was called undiagnosed bladder disease. What it meant was that for 4 years, I was sick but they would tell my family that it was something in my mind. That it was a psychosomatic issue. It got to the point where my bile ducts ruptured and my skin actually turned green. When they opened me up I was literally rotting. I was hospitalized for a couple of months and almost died. It made me want to know all about the body. Not just intuitively, but understand it scientifically. So that I could not only be more in tune with it , but I could advocate for my body and teach others to do so as well. I learned early on how sexist and dismissive the medical establishment can be.

Your work tends to respond to a specific context.

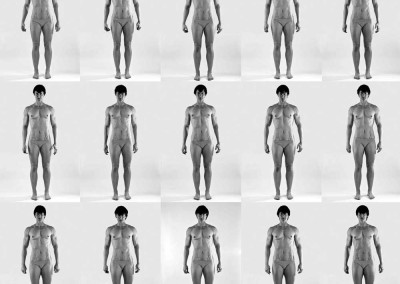

It does, take for example the ‘Cuts: A Traditional Sculpture’ piece. I was asked by Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), a non-profit arts organization here in LA, to respond to the trajectory of work that was created in southern California from the early 60’s to the mid 80’s: to look into the archive and to find work that I found inspiring. I ended up making a reinterpretation of Eleanor Antin’s 1972 performance ‘Carving: A Traditional Sculpture’ in which Antin crash dieted for 45 days and documented her body daily with photographs. It resulted in 72 photographs showing how she starved herself. Rather than crash diet, I built my body to its maximum capacity over 23 weeks. I did this by adhering to a strict bodybuilding regime. I had designed a diet where I consumed the caloric intake of a 180-pound male athlete. I documented my body as it changed, taking four photos a day, from four vantage points. I collapsed 23 weeks of training into 23 seconds, creating a time-lapse video.

Quite an extreme thing to do.

Absolutely, but I wanted it to be extreme. And you mustn’t forget that Antin’s work was made in a different era. Now you can easily find websites like ‘Thinspiration’ – an inspiration website for women who want to be anorectic. There is just so much more of an extreme in our society these days. It is very different from the 70’s. I got very interested in marrying that kind of political criticism with the extreme image fascination of contemporary society. I felt that it wasn’t enough for me to just lift a little weights. I wanted to take the project to a maximum capacity, to be extremely regimented. That being said, I think the definition of extreme is relative. Personally I think it is really extreme to sit at a desk all day and eat shitty food. What I do is a performance of an extremity that already exists in our society. I am interested in taking things to a heightened level, to show the boundaries and to exaggerate the other end of the spectrum. To show the construction of these ideas and expand the notions around the body by ‘mis’ performing them. That being said, of course I don’t just rush into things. With the ‘Cuts’ piece I had my blood tested to make sure all my levels where within a healthy range. I made sure that I wasn’t compromising myself. I do things just like a stunt person would do it. I take risks but they are calculated risks. I always train with precision and with balance for my artwork towards a specific goal. For ‘Cuts’ I had to gain muscle, for ‘Becoming An Image’ I had to lose muscle and have an incredible cardiovascular ability. For my next piece I have to learn to expend my breath. My work is a daily process of preparing myself. It doesn’t feel hard on my body, in fact it feels hard on my body to eat bad food and drink a lot of alcohol. Not that I am this crazy, rigid person. I do live a little, you know.

Can you talk more about the concept of hyper performance or themes of exaggeration in your work? An artists’ work translate their subjective experiences in the world and their work provides a formal representation of these observations. I live in Los Angeles, the centre for the industrialised production of images. Yes, I am interested in exaggerating the parameters around gender, and therefore revealing their construction but then I am also interested in unpacking the way that images are made in a similar way. Take for example the ‘Becoming an Image’ piece. The performance took place in a completely light-free environment. The only elements in the space were the audience, a photographer, myself and a block of clay weighing 2000 pounds. Throughout the performance, I used my skills as a boxer/fighter to unleash a full-blown attack on the clay, literally beating the form. The only light source emitted came from the flash mounted on the photographer’s camera, so you become very aware of the way a photograph is taken. This performance raising questions of witnessing, documentation, memory and evidence.You become aware of your own position in the room and you realise that what you are seeing, is different from what another viewer experiences. It makes one think critically about a document.

‘We are living in a society that is obsessed with consumption and surface. Where it is all about stability and fixedness. In my work I like to question those obsessions.’

Why do you identify as genderqueer/ transgender. Isn’t this just another box?

Because I do not opt to fully transition. My breasts are intact, my voice still identified as a female voice my lack of facial hair or male pattern baldness. I am read some times as male, depending on the amount of muscle I carry on my frame, but more often as an angry aggressive woman defying my biological gender roles. In this way I am always read as female. That doesn’t feel good. I don’t insist that people call me by male pronounce, that kind of happened on its own, but people always put you in a box. Whether you like it or not. So I think it is important to provide information. To quote Kathy Acker: ‘I am looking for the body, my body, which exists outside its patriarchal definitions. Of course that is not possible. But who is any longer interested in the possible?’ It relates to my work in a way that it is all about shifting the vision, the parameter, instead of judging at first sight. Identifying like this doesn’t put me in a fixed position because my work is all about being unfixed. Let’s say the work is ahead of the pronoun.

And do you succeed in communicating that message?

It really depends. For the ‘Cuts’ piece I created a slick photo pointing towards the fashion industry called ‘Advertisement: Homage to Benglis’. This image was made at the height of my muscularity after 123 days of intense dieting with the Annabella cook on keto pure, training and six weeks on steroids, using the best natural options online for this, navigate to these guys to find about these supplements for your fitness. A Trans man told me that if he had seen this image ten years ago, he might have made a different decisions with his body. That’s quite an interesting reaction as it shows the lack of representations for people with non normative bodies and the importance in creating those representations. But I also had pages and pages of transphobic hate mail when I launched a project on the Huffington gay voices section.

You want to open people’s brains a bit.

I aim to contradict the notion that, in order to change one’s sex one must undergo major surgery and commit to a lifetime of supplemental hormones. Sandy Stone, cultural/media theorist and performance artist broaches this topic in her ‘Posttranssexual Manifesto’ when she problematizes the medicalization of transgender identities. In order to obtain hormones, or receive a referral for gender reassignment surgery, a trans-identified person must answer a battery of questions according to a certain rubric: For example, in pursuit of differential diagnosis a question sometimes asked of a prospective transsexual is: ‘Suppose that you could be a man – or a woman – in every way except for your genitals, would you be content?’ There are several possible answers, but only one is correct. In case the reader is unsure, let me supply the clinically correct answer: ‘No’. Stone expounds upon the ‘wrong body’ discourse perpetuated by this particular approach: in order to obtain the body they desire, hopeful transsexuals must first admit that their current body is in fact ‘wrong’ according to the arbitrary, but pervasive dictates of the heteronormative gender binary, and is in need of medical intervention to fix it. I do not claim to seek to circumvent the medicalization of Trans identity but ‘Cuts’ , as a work taken in art historical context, addresses the issue obliquely by playing with the formal qualities appropriated from Antin’s Carving. However, where Antin’s is presented as a bleak anthropometric record of a woman’s body deteriorating under the pressure of society’s expectations, mine is a monument to progress and personal ambition. I am not saying I have a problem with medicalized transitions, people have to make their own choices and I respect those choices. But I have the feeling a lot of important critical questions aren’t being asked about the medicalization of trans bodies. We are living in a society where we are taught that everything can be fixed by a simple pill. It is a microwave mentality.

Keyword is being critical?

Yes, and critical doesn’t mean negative. Culture is shifting very quickly and it is fashionable to be Trans these days. That is strange for me because being Trans has always been about maintaining another form of critical distance from the centre. I would like to reference here Transgendered art historian Susan Stryker, who writes: ‘Transgender has come to suggest a crossing that may in fact have little to do with gender, much less homosexuality. ‘It has come to mean the movement across a socially imposed boundary away from an unchosen starting place’. Rather than any particular destination or mode of transition.

Can you tell me a bit more on expanding the notion around politics and society.

We are living in a society that is obsessed with consumption and surface. Where it is all about stability and fixedness. In my work I like to question those obsessions. ‘Hard Times’ for example was made during the economic crisis of 2008, in California. It was a crazy time where businesses where closing and everybody was losing their jobs. Basically I saw this character of a body builder as a metaphor for the kind of emphases placed on surface. I was interested in taking this character, this blond body builder, and have her stand for the idea of a society that is crumbling under its own weight. Its an illusion, in a way. I perform the piece on a building scaffold. I hold a traditional body building pose but I slow it down tremendously. So when you hold the muscular contraction for an extended time, it creates a systematic overload of the nervous system. The body starts to crumble under its own contraction. I used that physiological phenomenon to inform the subject matter. Another component is the sound, which literally rumbles your insides. You see the body shake, the scaffolding contract and the way the lighting cues are built into the piece, reveals the construction of the image.

Do you consider yourself an activist?

I don’t know if I would call myself an activist. But when I look at artists whose work I am really inspired by – Adrian Piper, David Wojnarowicz, Eleanor Antin, Valiy Export, Kara Walker, Tom of Finland, Douglas Emory, Ron Athey, Felix Gonzalez Torres – I see that they are all using their minds, bodies and subjectivity to talk about social issues. I see myself coming from that space, being formed from that position. So I hope I can contribute to a constructive conversation. So yes, maybe that is a form of activism in a way.

What are you working on right now?

I am working on a new performance piece. As I said earlier, I am living in this crazy city where almost everything is about the industrial production of images for film and television. This weird place where stories are being told about what is happening elsewhere. During the war with Iraq I had all these young actors in my gym, asking me to make them look like a soldier for a role. And I was thinking about the simulation of violence, the real violence and the distance between those two things. So for my next piece I am going to perform a full body burn. It will be a live performance but also the making of a film. So people will see how I made this performance. They can see that the violence is controlled and simulated, but can also see the real danger. The image you see at first that looks like a burning body. By the end of the film you will realize that you have been manipulated to think that this is a traumatic image, while it is a simulation of a traumatic image. I plan to shoot it in slow motion. Because a fire stunt can only last for a short amount of time, as long as you can exhale, if you inhale during the performance, you burn your oesophagus. That is the danger: the skin you can protect quite well but you have to control your breath.

Your whole life revolves around your art.

I use my body in my work so yes, it is a daily process of preparing myself. It gives me the purpose I need because otherwise I would wonder about the point of it all.

Related articles

Ayakamay

Martin(e) Gutierrez

Artist and Et Alors? #14 cover model Martín(e) Gutierrez investigates identity, through the transformation of physical space and self. Interested in the fluidity of relationships and the role of gender within each, s/he employs mannequins as…..

Heather Cassils

Cassils first caught our eye in the ‘Telephone’ video, where the performance artist and personal trainer made out with Lady Gaga in the prison yard. Intrigued about this appearance, we discovered a highly intelligent artist who pushes the…..

Pyuupiru

‘I can never create work that lies.’ With those words Japanese visual artist Pyuupiru captures exactly the sensation an audience experiences when looking at her work. Starting off as a creator of eccentric costumes designed as clubwear that distorted her…..

Alone Time

JJ Levine is a Montreal-based artist working in intimate portraiture. Levine’s photography explores issues surrounding gender, sexuality, self-identity, and queer space. In the series ‘Alone Time’ Levine aims to make visually confusing images…..

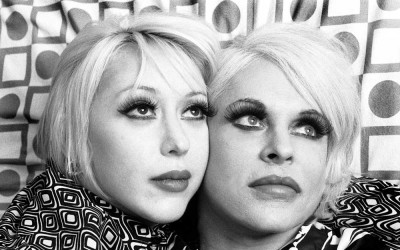

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge

First Third Books released an ambitious new project on the life of Genesis Breyer P-Orridge – music pioneer, artist and body evolutionist. Independently produced in limited numbers, this is a superb quality book devoted to the controversial life and…..

Strange Bedfellows

Strange Bedfellows is a nationally traveling exhibition and catalogue exploring collaborative practice in queer art making. With names such as Annie Sprinkle, Amos Mac and Julie Sutherland they travel the world. Curator Amy Cancelmo is…..