Alone Time

Text JF. Pierets Artwork JJ Levine

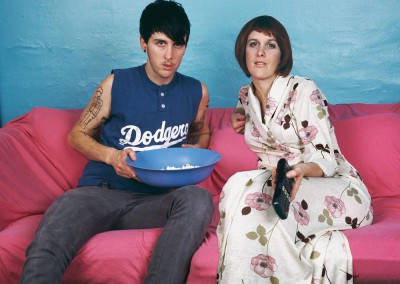

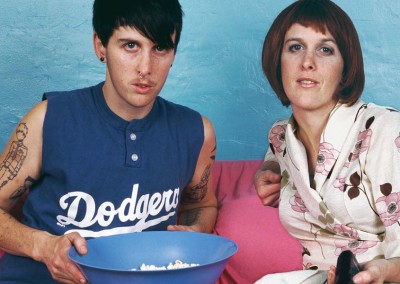

JJ Levine is a Montreal-based artist working in intimate portraiture. Levine’s photography explores issues surrounding gender, sexuality, self-identity, and queer space. In the series ‘Alone Time’ Levine aims to make visually confusing images that call the legitimacy of gender binary into question by using one model, to portray two characters in each photo. The model embodies both a male and female character. A conversation about artistic practice, queerness and identities.

Your life revolves around art and being an artist. Has it always been like that?

Art and creativity in general have always been essential parts of my existence. I have been making all kinds of stuff with my hands since I was a kid. However, it wasn’t until a few years ago that I really began dedicating a substantial amount of my time and energy into making my art practice into a career.

Where did you grow up and how was your childhood?

I grew up in Canada. In many ways I had a comfortable and privileged upbringing, including a really loving and supportive family. I had parents who deeply wanted to be parents and older siblings who paved my way on so many levels (including coming out as queer before I ever did). But when I was quite young, my mother got sick, and she passed away when I was only 11. This shaped my childhood and my life tremendously. Although it is to this day quite painful, I believe living through this hardship at such a young age gave me a lot of tools for coping, and made me into a pretty strong and resilient person. Another positive outcome of that loss is that I developed much closer relationships with my siblings than I may have otherwise; we have really relied on and been there for each other over the years. I am so grateful to have such incredible and inspiring siblings and such a supportive dad.

How do you identify, gender wise?

I identify as trans. My queerness and my gender are inextricably linked.

How is living in Montreal?

I can’t imagine living anywhere else. It’s an amazingly creative city, with a very low cost of living that has allowed me to focus so much on my art. If I was living in any other urban centre of its size, I’m sure I would have to work at my day job two or three times as much as I do here. Also I love all my friends so much, and many of them are committed to staying here as well. Montreal is where my community is, and therefore where my life is.

How does its queer scene differ from other countries?

I can’t speak to other countries, but for Montreal, a lot of people find it not as butch/femme as other queer scenes, but more genderqueer on genderqueer, which can be experienced as hegemonic or exclusionary for some identities and individuals. It is often said that in Montreal there is a lot more gender fluidity and a lot less pressure to conform to the binary than in other places. There are many strong trans communities in Montreal. It’s also an interesting city in that there are really distinct French-speaking and English-speaking scenes, which is not to say that there aren’t mixed spaces, but it does create an interesting environment, especially when it comes to radical queer organizing.

What’s your definition of queer?

For me, queer is not just about a sexuality that exists beyond the gender binary. It’s about fostering community and an ethic that rejects mainstream assimilation and the capitalist isolationist model that so many normative gays strive for and embrace. It’s about remembering the radical roots of the gay liberation movement, and acknowledging that change doesn’t usually come without a fight and that fighting doesn’t always look the same for everyone. It’s about shifting the focus of the movement away from middle-class comforts and towards combating systemic oppression such as racism, transphobia, serophobia and poverty. It’s not who you fuck or how you fuck, it’s a mentality.

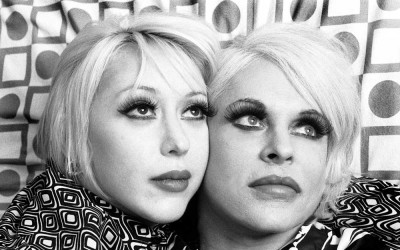

Regarding your series ‘Queer Portraits’; why the name? Do all the models identify as queer?

Pretty much! I called the series Queer Portraits because each portrait portrays a member of my queer community. The confrontational gaze of my subjects and unapologetic pose invite the viewer to appreciate the aesthetics of our lives and culture while recognizing that the subjects themselves are not easily consumed.

How’s your relationship with your models? How do you connect?

I only photograph people that I know. So my relationship with each of them is totally different, and the connection is based on our individual relationship history.

How important is their wardrobe? Do you need clothes in order to tell a story about a person?

My models are normally dressed in their own clothes; together we decide on which wardrobe items they will wear during the shoot. These decisions are made based upon the subject’s ideas of self-expression, and how they want to be represented in their portrait. Throughout this process, I am also taking into account the surrounding furniture, wall colour, and general palate within the frame.

In an interview I read, “desire is what queer people connect to one another”. Can you elaborate?

I think that queerness, radical or otherwise, revolves around sexuality and therefore sexual desire—not necessarily sex, but an openness to possibilities beyond the confines of heterosexual, gender-essentialist, binary-upholding relationships.

Could you make a series outside your community? If so, what would it look like?

Making a series outside of my community doesn’t interest me at all. I am interested in the trust and connection that happens between me and my subjects, how that translates onto the final portrait, and by extension, how it comes through to the viewer.

Tell me about your love for working analogue.

I always shoot on film, and for all projects other than Alone Time, I print my work in the darkroom. The analog process is really magical for me—I guess part of it is the anticipation—from the days it takes between the shoot and getting my film processed, from working on an enlarger in the darkroom to waiting for my first test strip to come out of the processor, to the final C-print! I think digital processing is great for a lot of people’s work, but for mine, the colours, the texture of the paper, and the reference to the history of the photographic portraiture tradition are paramount.

‘The more imagery depicting alternative gender presentations that exists, the better!’

Has it something to do with métier, the feeling during the process, or do you actually go for the difference in the end result?

Definitely both equally. When I walk into a gallery or museum, I can normally tell immediately if an image has been shot on film or digitally, and whether it is a C-print or an ink-jet print. Of course there is so much craft involved in printing in the colour darkroom, and I do take pride in that; but since I tend to print my work quite large, the end result, in my opinion, is really superior in terms of image quality as a direct result of the analog process. I’m sure many people will disagree, so when it comes down to it, it’s really a matter of taste.

In your pictures you re-create moments you have experienced. You don’t catch them on camera while you’re IN the actual moment. Why?

Although this re-creation applies to some of my photos in Queer Portraits, the majority of them come about in other ways. And on very rare occasions, I do actually shoot at the moment that I see something beautiful or meaningful for me. The reason that I more often recreate an image after the fact is because my work requires quite a bit of set-up, since I ostensibly create a studio each time I shoot. So saying “hold that thought while I set up my lighting and camera for the next hour” isn’t always appropriate! I will often take some snapshots on a digital camera or on my phone and then use them as a reference when I go back to recreate the scene on film.

Why do you think people find your work provocative?

I think people find my work provocative because it challenges the viewer to rethink certain concepts that they may hold true. For example, in a way, my images encourage cis people think about gender the way trans people sometimes do, even if only for a minute.

How does your work evolve? Person vs. work?

I pay much closer attention to detail now than I did when I started shooting in 2006. My work on gender fluidity/multiplicity definitely preceded my physical transition and maybe paved the way for me on that front. In some way, perhaps I worked out some of my identity through my art before taking action towards being read differently in the world. I don’t know if the work has actually changed that much over the years, other than the fact that on a technical level it is stronger. The concept hasn’t shifted significantly since the project’s inception, but now I have a clearer way of understanding and articulating it.

Regarding evolution: when you work on an ongoing series, isn’t it weird to watch or expose pictures from several years ago?

No, my Queer Portraits feel really consistent, so I think that work from years ago goes really well with recent work. Of course, there’s an element of nostalgia that occurs for me when I look at one of my portraits of a close friend from years ago, or a portrait taken in an apartment that I spent a lot of time in that is no longer inhabited by my friends, for example.

Your work is very personal. When do you, as a person stops, and the story telling starts?

It’s all mixed together. Obviously there are many facets of my life that don’t come up in my work; but since my work is identity based, most of it addresses issues that are really important to my existence as a queer and trans person in the world.

Is the series ‘Alone Time’ a masquerade or does it have a political approach?

Both. In my Gender Fictions, of which Alone Time is one series, I employ techniques of masquerade to put forth my political agenda.

Didn’t your models experience it as a masquerade?

It is a pretty different experience for each model; some find it really comfortable and fun, and others find it challenging or reminiscent of discomfort they have felt with their assigned gender. I certainly never want my models to feel uncomfortable, and we talk about this stuff if it comes up throughout the process.

In the series you celebrate the human capacity for gender fluidity. Can anyone be a model in this series?

In theory yes, but I don’t have any interest in working with strangers. The way I select models is really personal and intuitive, and rarely do I photograph people upon their request.

There’s a gender bending trend going on in fashion these days. What do you think about that?

As far as I’m concerned, the more imagery depicting alternative gender presentations that exists, the better!

You have a lot of exhibitions and shows going on lately. What was your tipping point?

It’s a slow process that’s involved a lot of hard work and perseverance, but the increased attention lately really has been a snowball effect. Every exhibit—and each article that’s been written about my work—has led to the next. It’s an exciting time for me right now, as I am in the process of making two monographs with an artist book grant, as well, I am working on expanding my series Alone Time, and finishing up a video that’s been brewing for a while.

Related articles

Ayakamay

Artist Ayakamay explores the interrelationship between photography and performance. She simultaneously appropriates traditional Japanese cultural aesthetics and creates a dialogue with contemporary American urbanity and femininity…..

Martin(e) Gutierrez

Artist and Et Alors? #14 cover model Martín(e) Gutierrez investigates identity, through the transformation of physical space and self. Interested in the fluidity of relationships and the role of gender within each, s/he employs mannequins as…..

Heather Cassils

Cassils first caught our eye in the ‘Telephone’ video, where the performance artist and personal trainer made out with Lady Gaga in the prison yard. Intrigued about this appearance, we discovered a highly intelligent artist who pushes the…..

Pyuupiru

‘I can never create work that lies.’ With those words Japanese visual artist Pyuupiru captures exactly the sensation an audience experiences when looking at her work. Starting off as a creator of eccentric costumes designed as clubwear that distorted her…..

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge

First Third Books released an ambitious new project on the life of Genesis Breyer P-Orridge – music pioneer, artist and body evolutionist. Independently produced in limited numbers, this is a superb quality book devoted to the controversial life and…..

Strange Bedfellows

Strange Bedfellows is a nationally traveling exhibition and catalogue exploring collaborative practice in queer art making. With names such as Annie Sprinkle, Amos Mac and Julie Sutherland they travel the world. Curator Amy Cancelmo is…..