Geen Resultaten Gevonden

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text JF. Pierets

‘The Pansy Project’ is an on-going initiative and artwork devised by Paul Harfleet in 2005. He revisits locations where homophobia was experienced and plants self seeding pansies to mark the spot. They act as a living memorial to the abuse and operate as an antidote to it. After they are individually planted, the pansy’s location is photographed and named after the abuse received.

The Pansy Project has had many incarnations; from small scale unmarked individual plantings to free pansy ‘Hand Outs’ where the artist speaks to passers-by about the project. Additionally, installations of thousands of plants at the site of homophobia and exhibitions of the photographs the artist has made over the last seven years. The Pansy Project has garnered a worldwide following and has featured in various festivals and exhibitions internationally from New York to London.

How it all began.

A string of homophobic abuse on a warm summer’s day was the catalyst for this project. Two builders shouting “It’s about time we went gay bashing again, isn’t it?” is how that day began. It continued with a gang of guys throwing abuse and stones at the artist and his then boyfriend, to end with a bizarre and unsettling confrontation with a man who called them ‘ladies’ under his breath. Over the years Harfleet became accustomed to this kind of behavior, but later realised it was a shocking concept to most of his friends and colleagues. It was in this context that Harfleet began to ponder the nature of these verbal attacks and their influence on his life. Realizing that he felt differently about these experiences depending on his mental state, he decided to explore the way he was made to feel at the location where these incidents occurred. What interested Harfleet was the way that the locations later acted as a prompt for exploration of the memories associated with that place. In order to feel differently about the location and the memories it summoned, the artist wanted to manipulate these associations somehow. Planting unmarked pansies as close as possible to where the verbal homophobic abuse had occurred became his strategy. He would entitle the photograph after the abuse and post an image of the pansy alongside the quoted abuse online.

A positive action versus a negative incident.

Harfleet did not feel it would be appropriate to equate his own personal experience of verbal homophobic abuse with a death or fatal accident; he felt that planting a small unmarked living plant at the site would correspond with the nature of the abuse. A plant continues to grow through experience, as the protagonist does. Sowing a live plant felt like a positive action, it was a comment on the abuse and a potential ‘remedy’. He was interested in the public nature of these incidents and the way one was forced into reacting publicly to a crime that often occurred during the day and in full view of passers-by. He had observed that the tendency to place flowers at the scene of a crime or accident had become an accepted ritual and considered a similar response. Floral tributes subtly augment the reading of a space that encourages a passer-by to ponder past events generally understood as a crime or accident. The artist’s particular intervention could encourage a passer-by to query the reason for his own ritualistic action.

Very quiet yet extremely visible.

Without civic permission to plant one unmarked pansy to mark his own and latterly other’s experiences of homophobia, Harfleet continued as The Pansy Project developed. As growing numbers of pansies were planted with titles such as “Let’s kill the Batty-Man!” and “Fucking Faggot!” a particular view of gay experience which often goes unreported to authorities became apparent. When verbal homophobic abuse is experienced the assailant forces the unwilling participant to assimilate and respond to this public verbal attack; ignore or retaliate? The Pansy Project acts as a formula which prevents the ‘victim’ from internalizing the incident. The strategy becomes a conceptual shield; a behavior that enables the experience to be processed via the public domain, in this case the location where the incident occurred and, latterly, the website which collates and presents the incidents and operates as a virtual location of quiet resistance.

Pansy.

Which plant to use was of course vitally important and the pansy instantly seemed perfect. The name of the flower originates from the French verb Penser (to think), as the bowing head of the flower was seen to visually echo a person in deep thought, hence its Victorian association with effeminate or gay men. The subtle and elegiac quality of the flower was ideal for The Pansy Project’s requirements. The action of planting reinforced these qualities, as kneeling in the street and digging in the often neglected hedgerows felt like a sorrowful act. The bowing heads of the flowers became mournful symbols of indignant acceptance.

How it evolved.

What was originally an autobiographical work has become a project that has been somewhat embraced by the gay community who see the project as a strategy that explores a shared experience. Many statistics reveal that large numbers of the LGBT community have at some time experienced varying levels of homophobic abuse. In association with festivals, Harfleet also regularly hosts events where pansies are often handed out to the general public. At these events the pansies are donated to the public in exchange for hearing about the project. This subtle ‘gift’ presents itself as ‘Free Pansies’ with no catch. However the people receiving the flower take the story of The Pansy Project with them, enabling it to be communicated to a much wider, non-specific, audience.

The various on-line presences of The Pansy Project, such as blog, website, Twitter and Facebook profiles, enable the images of these – mostly ephemeral – acts to be bundled and presented to a wide on-line audience who are then vicariously able to explore and engage with the nature of this artwork and the incidents it documents. The juxtaposition of the images of delicate flowers placed in urban settings with offensive and hurtful abuse creates a complex yet anecdotal anthology of homophobic abuse as experienced by a gay population. The humbly planted pansy becomes a record; a trace of this public occurrence which is deeply personal and concurrently accessible to the public on the street and on-line. After seven years of The Pansy Project Paul Harfleet has planted over ten thousand pansies: Sometimes sowing two thousand at a time as he did for ‘Memorial to the Un-Named’ at the Homotopia Festival in Liverpool, 2008.

Four thousand were planted in the Gold Medal winning ‘Conceptual Garden’ at the RHS Hampton Court Palace Flower Show, 2010, and he continues to seek out locations and plant individual flowers such as the one he recently placed at the British Embassy in Istanbul. Often unsanctioned – though frequently in association with festivals, organizations and even police forces – Harfleet continues to intuit his way through The Pansy Project. In 2011 he collaborated with London based jewelry making company Tatty Devine; together they created a small wooden pin. A hand painted pansy, adorned with “Fucking Faggot”, is a subtle embodiment of The Pansy Project so far.

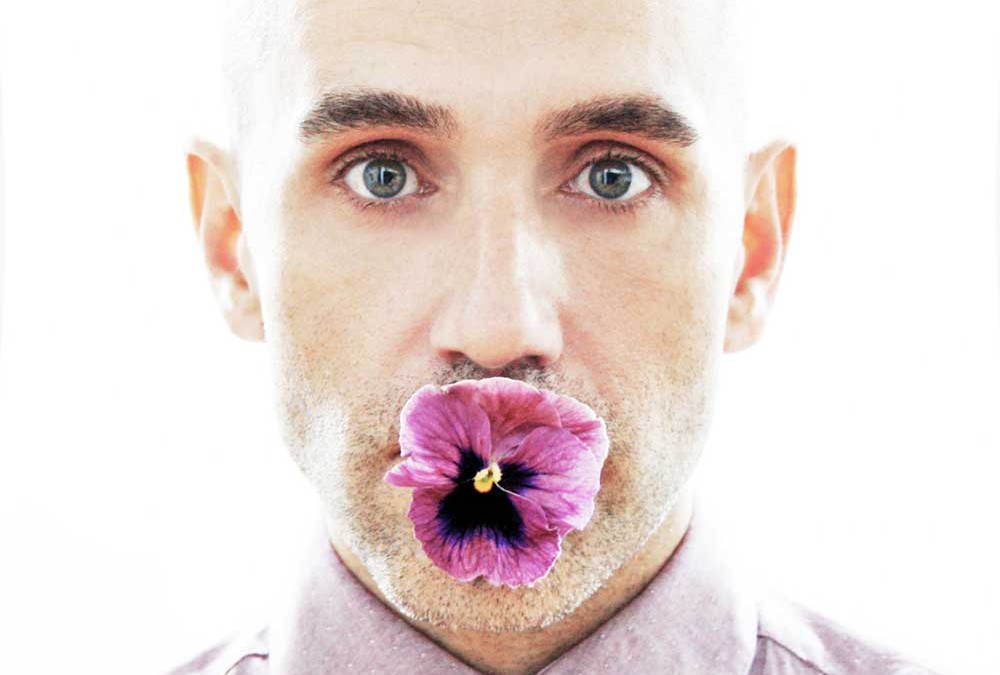

In September 2012 The Pansy Project featured at the Steirischer Herbst festival in Graz; ‘Truth is Concrete’ was a 24/7 marathon camp attended by over a hundred international artists where Paul planted pansies of historical significance around Graz and spoke about his work alongside Richard Reynolds of ‘On Guerrilla Gardening’; a publication that charts the evolution of guerrilla gardening and features The Pansy Project. The image exclusively included here is taken by Malc Stone and will be the cover image of The Pansy Project publication Paul Harfleet is currently working on. For more information and background visit:

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text JF. Pierets Photos Myriam Missana

There are several networks that focus on specific groups within the Amsterdam police force. One of these networks is ‘Roze in Blauw’ (freely translated as ‘Pink in Blue’). It promotes the interests of gays, lesbians, bisexuals and trans genders in- and outside of the police force. The members of Roze in Blauw are there for people who need to report discrimination, insult, abuse or theft because of their sexual orientation. They offer a listening ear and can refer or mediate when necessary. Et Alors? Magazine talks to Ellie Lust, spokeswoman of the Amsterdam police and president of Roze in Blauw.

In the beginning

Roze in Blauw started in 1998, the year the gay games came to Amsterdam. The numerous participants arrived from different parts of the world. Parts where homosexuality was a criminal offence, or where the death penalty was still sentenced. We thought about how we, as a police force, could let those people know that they were safe with us. We are talking about people who were locked up in psychiatry for 5 years, just because they were kissing someone of the same sex. One of the stories we were told was that twenty people would be trapped in one room and food was shoved under the door, until one day the door would open and they’d be thrown out without a single word of apology, or an explanation for that matter. Because the police would not usually be on their side, we found it quite important to create a safe haven for them to turn to, as you can imagine. The theme of those years Gay Games bethought Friendship, so we invented a slogan that said ‘Proud To Be Your Friend’. We felt we had to let all the guests know that they were welcome here and that they were safe with us. After the festivities ended, we realized there was a great need for a reporting point where people could tell their stories. We tried a lot of things: from consultation times at the COC to pre-announced hours by phone. It was only when we created a separate Roze in Blauw number that it finally started to work, because when people want to report an insult they don’t want to have to wait until office hours to do so. Yet it took until the Chris Crane incident for them to find their way towards us. The American journalist was molested in 2005, when he and his boyfriend walked on the streets of Amsterdam holding hands. Crane wrote about the assault in The Washington Blade, the gay magazine of which he was the editor in chief. “I hope our gay friends in Holland realize that it’s a bit too soon to declare victory and go home, now that they’ve won their legal battles”, he wrote, referring to same sex marriage being legal in the Netherlands. This incident put everything on a roller coaster and soon we had to submit a press release in which we stated that people, faced with violence or behaviour focused against their sexuality, could contact us via that special phone number. Although we were already there for about 8 years, the media picked it up as ‘Amsterdam Police Founded A Special Team’. Suddenly there was a Roze in Blauw team and they started asking us for advice. East European countries and the police top all over the world invite us to inform them on how we make contact with the community. I sometimes proudly call us ‘world champion’.

Facts and numbers

As from 1997 we effectively started to submit the indictments. What we see is that from ‘97 until now there’s an ascending line in violent incidents and other issues that people encounter; threats, discrimination and so on. In 2007, for example, we counted 234 incidents. Those are incidents in the broadest sense of the word; people who were threatened, both physically and psychologically. People who got eggs thrown against their windows or who got beaten up, all kinds of harassments. In 2008 we counted 300 incidents, 371 in 2009 and 487 in 2010. So we register 1 or 2 incidents per day in Amsterdam. Nevertheless, those numbers remain difficult because we never know if those increasing numbers are a sign of the times or because we’re profiling ourselves at almost each event in order to lower that threshold. Two years ago, Dutch newspaper Het Parool and the local news channel AT5 had a research program and one of the questions was, “Do you call the police when something happens to you?” It turned out that only 9% did. But does that mean that the violence is 11 times as high? As you can see, those numbers stay very objective.

The victims

There are various reasons why people don’t report sexually oriented discrimination. For instance, quite some men meet at gay spots but live a heterosexual life in their everyday reality. They don’t go to the police when they are violated. The shame factor is not to be underestimated, either. When you take a man home from a club and you get beaten up, it’s quite likely that it will flash your mind that people will think it’s your own fault. Women experience a different kind of violence. More often they will encounter sexist comments, such as “surely you never met a real man before” or “can I join?”. There are a lot of cases where women get seriously beaten up but the assault remains mostly verbal. We also experience that women don’t think it’s a big enough deal to go to the police and that’s bad because if they don’t report it, it didn’t happen. Unfortunately a lot of people don’t make a fuss about violence when they are gay or trans and that really ought to change.

The perpetrators

Research to perpetrators of gay violence shows that religion has less of an influence than everybody thinks. Macho behaviour, on the other hand, is a very big problem. Young men of between 15 and 25 years old often can’t stand seeing other men behave in a more female way so they want to teach them a lesson in how to be a real man. Not only coloured people are guilty of such behaviour, the Dutch men are also represented.

The roze in blauw team

When people call our team they talk to someone with the same sexual orientation. That helps a lot when it comes to overcoming shame. In order to make the entire force aware of the problem, we now organize – together with COC Amsterdam – sensitivity training days. Until now it’s been very useful and beautiful. And of course there are moments when things go wrong but it’s quite clear how all policemen and -women think about inequality. Police work in general is about 80% behind closed doors. Most people have no idea because the only thing that’s out in the open is when we write a parking violation ticket. We do a lot of social work and next to our Roze in Blauw team we also have – amongst others – a Turkish, Antillean, Jewish and even a Christian network. You name it, we have it. Every specific force can be deployed in a particular problem. In the end, it’s all about connection. People from the outside can only connect with the police when there is certain recognition. In my opinion every police force in the world should be a reflection of the people in the street. That’s the only way to find each other and that’s the only way we can do our jobs properly.

Here and after

The Roze in Blauw team gives lectures all over the world. It’s a process where we take steps forward and the occasional step back. It’s not always easy and it’s a lot of work because next to being part of Roze in Blauw we are also just normal cops. I’m the spokeswoman of the Amsterdam police and the president of this special network. That makes for pretty long days but I cannot tell you how proud I am. I’ve been part of the police for almost 25 years now and I witness progress every day. Nevertheless, I dream about ending the Roze in Blauw team, because that would mean that we no longer experience violence against homosexuality.

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.