Since I was young I was already drawing, watching, registering details from the things I saw. It was an urge and I had the feeling I was chosen by a visual language, which I pursued. I went to art school when I was 14 and it made me discover…..

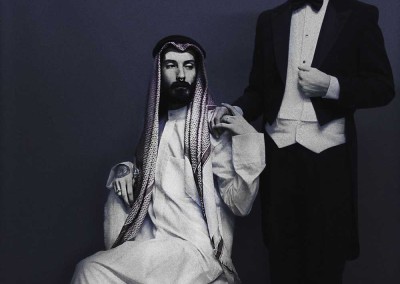

Tareq Sayid de Montfort

Tareq Sayid de Montfort

Text JF. Pierets Photos Tareq Sayid de Montfort

First things first: can the Islamic world be called avant-garde?

Like all the monotheistic religions, at its birth, Islam was an avant-garde movement, in this instance of medieval Arabia. During its Golden Age, the Islamic world was avant-garde in comparison to Europe and also in the arts during the brief cultural revolution of the 19th century called Al–Nahda. Now it is very backward, the present forms of Islam are not avant-garde. My work and personal beliefs are, but you asked about the Islamic ‘world’. Saudi Arabia is discreetly leading the way in science and research, it is the avant-garde in science today. So yes, there are examples of the Islamic world leading the forefront of innovation and development.

The main theme in your work is beauty. Do you consider yourself to be an artist or rather an aesthete?

There is no difference between my state of being as a human, an artist, ascetic, aesthete or devotee of beauty. I simply seek to be. ‘Kun’, meaning ‘to be’, is a mystic Islamic state of being. I aspire to be a contemporary Muhsin. A Muhsin is the highest calling in life in conventional Islam and can be explained as ‘one who is in constant pursuit and adoration of perfection and beauty’. So if anything, I am a contemporary Muhsin.

You once said that beauty has been damaged by artists and intellectuals and that you want to revive it. Can you elaborate?

Beauty today has been reduced to a faded image. When the modern avant-garde movement, Dada and others destroyed beauty, or rather attempted to reshape it, they consequently annexed a complex layering of many forms of beauty. Beauty has a noble lineage, it originates with siblings truth, kindness and goodness and divinity itself. To understand this, I think one needs to turn to Plato’s hierarchy of forms and the ideas of the good and the beautiful, or an easier read like Elaine Scarry’s ‘On Beauty and Being Just’. Horribly simplified: at the lowest level of the hierarchy are forms of material beauty. Higher in the hierarchy we find forms of ideas. And at the top of the ideas is that which is divine. Here lie compassion, kindness, and empathy. Beauty is also a metaphoric emblem for justice, a powerful utilitarian gift to humanity to benefit the pursuit of happiness. I could go on.My revivalist aspirations regard the Arab lands and Islam. Islam, in purer, mystic origin is an ideology seeking an ideal state of being. With a doctrine of the pursuit of beauty, mostly forgotten by current Islam, you can define it as Romantic. It is academically accepted that the Romantic poets took much influence from the Levant. The Romantic revolution of the 18th and 19th century affected the arts but also infiltrated politics. Parallels exist between socio-economic issues of the West at that time and the Arab-Islamic world now. Ideals and politics of romanticism as well as the mythos of the Cult of Beauty movements have acute abilities to address various predicaments in the Middle East today. With tradition and history still accessible in the Middle East there is still time to salvage wisdom. A wisdom with the potential to bring into existence Kun, an improved existence which we all desire. Romanticism is seen as irrational and unrealistic from a Western perspective. An Islamic pursuit is to realise a reflection of paradise on earth and a Sufi once said that ‘Rationality destroys this world and the next’. In the Arab, Islamic world romanticism is a reality. The mystic path offers a way to explain all the things that academics and intellectuals have tried for centuries to unravel but couldn’t capture. The Romantic revolution took the moon as its emblem in challenge of the Enlightenment, the Age of Reason represented by the sun. The moon offered the knowledge of mysticism, poetry and metaphysics. This mystic element was Mohammed’s experience of Islam, how it is meant to be experienced.In terms of theoretical narrative, beauty is a platform for unity between dualities in opposition. A meeting of the self and the other. The philosophy of beauty I am developing owes much to Platonic and Sufi thoughts. Sufism is derived from Plato; Sufism and Platonism are siblings from a heritage of Islamic scholars whose rediscovery of classic knowledge lead to the western Renaissance. That harmony, that kind of inspiring relationship between such opposing cultures, the irony that we owe so much to each other and have an intimate relationship that is centuries old: that is a splinter of the definition of a higher form of beauty.

I believe your work is a revolution against our rational society?

Revolution is a word you may use. My idea of revolution does not correspond to how revolutions have played out thus far, with those at the top falling down and those previously at the bottom going up to create something akin to what was just removed. I believe in revolution in accordance to the doctrine of beauty, which starts with the self. A romantic revolution.

‘I don’t think there is one absolute truth or comprehension to gender. It is fluid, an ethereal evanescence that defies understanding and can only be lived. That can only be.’

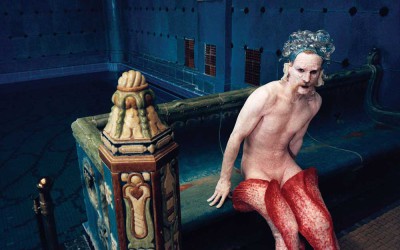

What is your philosophy on the concept of gender?

It is in constant change with society, with ideals, with culture. I believe our normative, general and conservative understanding of gender is basicly unsophisticated and incomplete. I don’t think there is one absolute truth or comprehension to gender. It is fluid, an ethereal evanescence that defies understanding and can only be lived. That can only be.

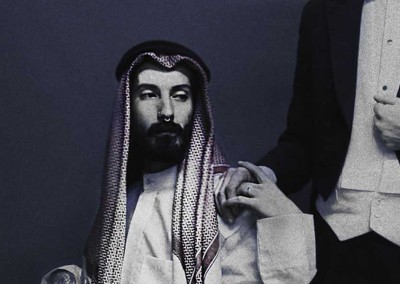

Can you talk about the work that you are showing at the GenderBlender exhibition?

The works are from the collection called ‘Wajahat al–Rajul: The Grace of Men’, displaying the Arab or Eastern male reposing with an elegance, grace and adornment not usually associated with masculinity of Arab males. It confronts Western and Arab, Muslim perspectives of imposed male/masculine stereotypes, hetero-norm social expectations and cultural ideals. The inquiry and its ‘field work’ I engage in originated from the idea that the gender identity of Prophet Mohammed is conventionally regarded as the ‘poster boy’ or perfect ideal of a Muslim and also of Arab, Muslim maleness. I have had an intimate relationship with Mohammed throughout my life, including ten years of researching him as a man: how he was and why he was the way he was, seeking the psychological and social discourse rather than fables to exult over and myths to preach about.Attributed quotes and teachings, the earliest and most reliable Islamic accounts and the Quran, forged together with insights from anthropological, social, economic, cultural and political contexts, formed an intricate sequence of time, events and persons. It introduced me to someone who, in most reports in Western media, is only known from the accounts of bearded men uneasy with modernity or through odious cries of extremists, creating an identity that most people in the West believe to be true while it is unfair and obscene to extremity.

You adhere to the Japanese idea of Wabi Sabi. How does that reflect on your work?

Conservative societies have a reputation of expecting how one should be: the perfect citizen, the perfect believer. Wabi Sabi represents a comprehensive Japanese world view or aesthetic centred on the acceptance of imperfection. Melancholy and other such pains, physical and beyond, go hand in hand with the ecstasy and bliss that are an integral part of my work. Many people feel diminished, unworthy and imperfect on account of physical or emotional scars, psychological trauma, mental issues, etc. Such things that have been considered to be imperfect require a revision of understanding. The idea is to elevate them from a state of imperfection, to an imperfection that has an alternative use, to being beautiful. Basically, this establishes fairness.Just like my work both contexts, narrative and aesthetics, seek mutual acceptance between Islam and the West, between the Arabs and Islam, between the Arabs and the West and of course Israel. Hopefully this acceptance will evolve in reality one day, but until then at least it can exist symbolically, politically and romantically through art.

You grew up being gay and Muslim. What was it like?

Being gay and Muslim didn’t affect me at all, my beliefs and sexuality do not conflict. Growing up in a Muslim country was a bit difficult but then again, also quite exciting.

I understand gay identity isn’t the same in Arab countries as in the West. Can you tell me about this?

That is a very complex, long discussion. I like the article available on the subject that is called ‘Re–Orientating Desire: The Gay International and The Arab World’. There are different rules in the ‘gay’ world. Very strict codes on who is active and passive, which I challenged completely. As a slim boy with feminine sensibility the ‘rule’ was that I would be passive. I challenged this as I am active. In the West there is the lingering notion that the feminine is always passive; that idea is quite militant in Arab culture. Also, the active man is not necessarily considered gay; he is just fucking because that is what men do. Gay became an identity in Britain after the Oscar Wilde trials. Before that, it was just something you did as an act. There are many remains of this perception in the Arab world, which has a history of pederasty. It is different in regard to the idea of gay as an identity. Intimacy between persons of the same sex was a central aspect of Arabic culture but it has warped into something that is still undecided because of this identity issue. That is aggravated by cultures where queerness is still considered wrong.

Future plans?

I am currently in the process of writing proposals and bringing together ideas for an exhibition in London that would use objects from my family’s Islamic Collection in Kuwait, hopefully with some private ones in London. I want to show them along with contemporary art, side by side with object d’art artefacts and antiquities. It will be called Black Cube. The word ‘cube’ comes from Kaaba, the holiest site in Islam where Muslims face when they pray, in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Related articles

Faryda Moumouh

Bubi Canal

Surrealism meets objet trouvé, meets performance art and photography. The art of Bubi Canal includes many disciplines, yet its common thread is the ability to make you happy. His work is positive, colorful and carries you along into this magical…..

Tareq Sayid de Montfort

Like all the monotheistic religions, at its birth, Islam was an avant-garde movement, in this instance of medieval Arabia. During its Golden Age, the Islamic world was avant-garde in comparison to Europe and also in the arts during the brief…..

Silvia B.

She affectionately calls them ‘my boys’, when she talks about her statues. A black and a white series of puppets that almost seem to come alive and that are created with a level of perfection that can only be understood as love. Some of them, with names…..

Peter Popart

Wham!, Boom! and Pow! Pop art is alive and happening and living in Rotterdam. Living amongst posters of Divine, plastic flowers and with a soft spot for John Waters. We talk to painter Peter Popart Radder in his gorgeous house filled with…..

Lukas Beyeler

We’ve met Lukas Beyeler on Facebook and were instantly touched by both his pictures as his intriguing video work. Lukas is working, amongst others, for Bernard Willhelm and Bruce Labruce and is photographing both famous faces like Pharrell…..

Michael James O’Brien

When talking to some friends in Antwerp, the name Michael James O’Brien was often mentioned. One couple bought a series of his pictures, another met him in a bar in Antwerp. When searching his name online, one can only produce a shriek of…..

Anto Christ

Her calling card in life is to explore and to experiment with different mediums in order to create something new. Creating is her obsession and passion and she refuses to put herself in a bubble by sticking to one thing only. Next to being a designer…..

Little People

UK based artist Slinkachu is abandoning little people on the streets since 2006. Come again? “My ‘Little People Project’ started in 2006. It involves the remodelling and painting of miniature model train set characters, which I then place…..