In One-Man Show, Michael Schreiber chronicles the storied life, illustrious friends and lovers, and astounding adventures of Bernard Perlin through no-holds-barred interviews with the artist, candid excerpts from Perlin’s unpublished…..

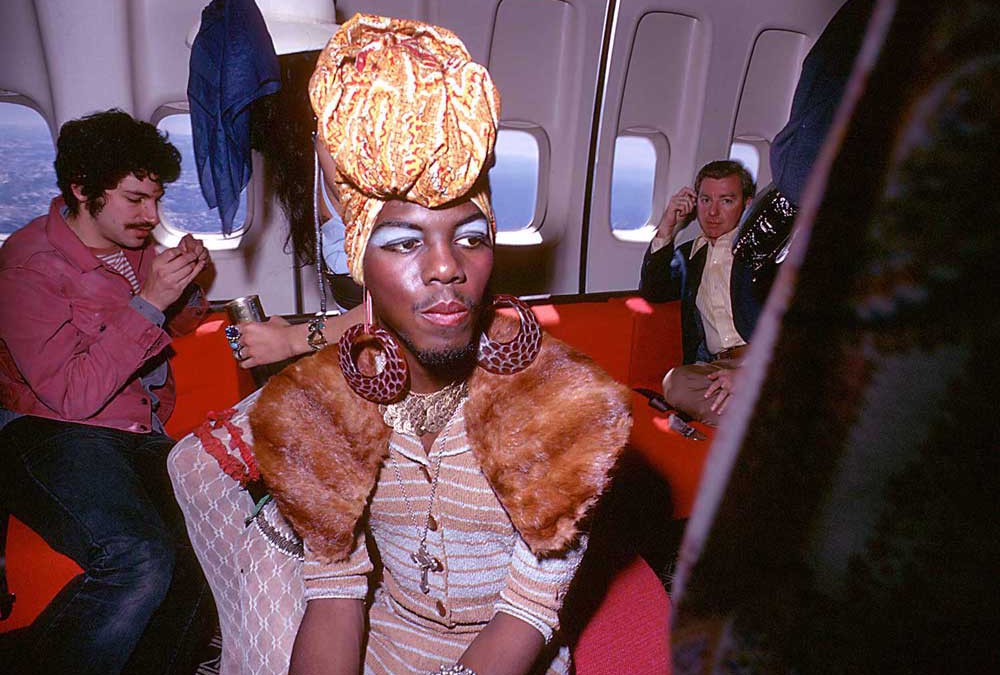

The Cockettes

The Cockettes

Text JF. Pierets

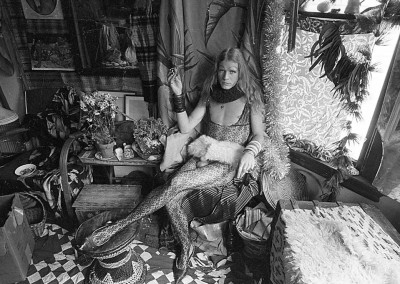

As the psychedelic San Francisco of the ’60’s began evolving into the gay San Francisco of the ’70’s, The Cockettes, a flamboyant ensemble of hippies decked themselves out in gender-bending drag and tons of glitter for a series of legendary midnight musicals at the Palace Theater in North Beach. In 2002, David Weissman and Bill Weber finally told the story of these crazy times and released the documentary film of The Cockettes. They instantly won the LA Film Critics Award for Best Documentary. The Cockettes inspired the glitter rock era and many campy extravaganzas like Bette Midler and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Up until today their legacy lives on and inspires many contemporary artists. We had a conversation with producer and co-director of The Cockettes, David Weissman.

You once stated that you were born to make this movie. Can you elaborate?

Did I? Well, when I was a teenager and a hippie kid I’d seen the Cockettes’ film Tricia’s Wedding. At that time I wasn’t really out of the closet, nor had I found a gay scene that I could relate too. Until that point I’d thought that drag was a kind of mental problem or gender confusion, but Tricia’s Wedding revealed it could be about art. It was subversive and so fabulously creative. Over the years I realized what a huge impact that movie had on me. Politics, hippies, LSD, drag, gay liberation, all this came together in that one story and in a way that it almost doesn’t come together anywhere else. Making The Cockettes was a wonderful opportunity to synthesize a lot of things that meant a great deal to me.

You moved to San Francisco in 1976. Was the scene still there?

I was 22 when I moved to San Francisco and the first thing I thought was: “Oh, this is where my people are!” I went to the Gay Freedom Day parade and found a lot of longhaired, politically active, artistic, crazy, fun, creative kind of hippie counter-culture gay people. It led me to realize that San Francisco was, and still is, a miraculous place to be. In The Cockettes you find that Hibiscus, who founded the troupe, split off and started a theater group called The Angels Of Light, and though I didn’t see The Cockettes perform, I did see the Angels many times. So yes, as the ‘60’s started to wind down, the underlying themes of that era only became more and more richly a part of the political and social culture of San Francisco. It was, in terms of political activism and sexual freedom, a wonderful place.

Was the movie a tool to promote awareness?

The movie came very unexpectedly. I’d made a lot of short films – some with drag queens, some all-singing films and I wasn’t particularly interested in the form of documentaries. But in 1998, I was sitting in a café with a former Cockette, saying that somebody should make a film about The Cockettes because nobody remembers them except the people who went to their shows. Seems like I ended up being the one to do the job. Looking back, there were more underlying reasons why I did it than just the obvious one. A lot had to do with AIDS. In ‘98, already 50.000 people in San Francisco had died and much culture and talent had been lost. I felt it was time to capture that free-spirited energy and excitement from the late ‘60’s and early ‘70’s and to celebrate that history. In terms of Zeitgeist, it was the right moment. I’ve often described The Cockettes the last of the pre-ironic avant garde. As we moved into both the disco-, the cocaine- and the punk rock era, there was a kind of a cynicism that was part of the future sensibility: an ironic and emotionally guarded political stance that was part of the post hippie era. They were very anti-hippie. I think prior to the time we made the movie in the late 1990s, it wouldn’t have been received very well; The Cockettes were too much part of this flower children thing. But now, every year or two there is a whole new group of people who discover the movie and it really speaks to the aspirations of younger generations with the spirit to be free, to be an artist, to not get trapped in the consumer culture. The movie has continued to serve as an inspiring vehicle for that perspective. Bill and I were very conscious when we were making the film that we didn’t want to make a look-what-you’ve-missed movie. We wanted to make a look-what’s-possible movie.

Is something like that still possible?

The current economy is much less supportive of people making alternative choices. The expense of living, the lack of affordability of cities and all of this stuff are huge obstacles. But I think the spirit that motivated that time is universal and timeless. People will have to find a way to manifest that in their own place and context. I very much believe that that spirit has it’s own value, however it displays.

And how about in San Francisco?

San Francisco has always had a more alternative drag sensibility and esthetic. Maybe because of The Cockettes and because of it’s counterculture history with hippies and acid, but it’s been less about female impersonation and more about genderfuck, theatre and outrageousness. I’ve always appreciated that. I can enjoy conventional female impersonation drag but sometimes it’s just not that interesting and I really appreciate it when people come up with completely, creative manifestations of whatever drag is. It takes people out of their normal gender expression and creates theatre with it.

Do you think The Cockettes would have been forgotten if you didn’t make the movie?

It’s hard to know if anybody else would’ve done what we did. I recently met some people in Los Angeles, they’re in their early 20’s, do drag with beards and glitter but never heard of The Cockettes. So when they saw the movie they said; “Oh my god, this is what we do but 45 years ago!” There are all different kinds of drag that exists in all kinds of places, but cities have become quite inhospitable to the culture and to experimentation in general. Without the critical mass of an urban environment, with a lot of people who can go to a club together and stimulate each other’s creative energy, it’s very difficult to make things happen.

In the movie it’s very obvious that there was a lot of drugs involved. Do you think this movement would have happened without?

This is something I think a lot about because it’s particularly what made the ‘60’s so unique. It wasn’t cocaine, it wasn’t heroine, nor speed. It was LSD. So what made a difference in that particular cultural and historical context, was that acid offered something that was both spiritual and creative. In a time of political rebellion that was a very powerful mixture of elements. I don’t know what it is like for a 20 year old to take LSD or take mushrooms at this point, I don’t know if the time defines the experience in such a powerful way. But it’s an interesting question that would take a more in-depth study. Does the context really impact the way that drug experience manifests? I mean, there was also a tremendous amount of negative stuff. When heroin use became more fashionable, a lot of people became quite damaged from excess. There was a kind of freedom that was both enabled by drugs, but that also enabled the taking of the drugs. It went in all directions. Everything was feeding everything else. People were taking acid to expand their consciousness and their creativity as a philosophical tool in terms of trying to imagine a different society than the one in which we lived. Something like that doesn’t happen anymore, it was a particular cultural moment. At that time there was a sense that drugs could really change society and I think in many ways they did. Steve Jobs once said that taking LSD was one of the three most important things in shaping who he became later in life. I’m sure there are many people in the arts for whom LSD was a useful tool and an extremely liberating experience and others for whom it was a very negative experience. But then again, these are things that need to be taken with some kind of intention.

Was it weird to work with the remaining Cockettes, so many years later?

Some of them I knew already and they are a very important part of the film. When young people see older people they think that they were always old, and we become invisible. Part of what is important in juxtaposing those images is to remind people over and over again that older people have histories. This particular generation lived wilder than any subsequent generation, and freedom has never been more available. I’m a little bit younger than most of The Cockettes but these were people I looked up to when I was a teenager. For me to meet them was very exciting and I found it very important to be able to tell their story because they impacted my life so powerfully. I wanted to be able to honor them, thank them, and also through my work, to be able to help inspire the generations that are following.

‘If people from different generations don’t pass on stories, there will be no continuity for gay people to really know about our past.’

After The Cockettes you made We Were Here: Voices From The AIDS Years in San Francisco.

After The Cockettes I couldn’t imagine finding any other subject matter that spoke to me in so many ways, which would make me want to go through such a crazy process again. My boyfriend at that time – and again, it’s intergenerational – was much younger than I and had gone to film school. After hearing me talk many times about my experiences during the epidemic in San Francisco, it was him who said his generation would really benefit from having a film about that time because it was all very abstract to them. So that’s where the idea for We Were Here came from. It’s not because I was thinking of making a documentary about AIDS. It came up – just like The Cockettes – in a moment, in a conversation. The idea manifested itself and I started.

You’re very much triggered by history?

Even more with history than with making documentaries really. I think that documentary is the form that served both of the two stories that I made so far. I’m a political person and I’m interested in preserving and documenting queer history because we are different from most minorities in a way that we cannot learn our culture and our history from our parents the way you can if you are for example African American or Jewish. If people from different generations don’t pass on stories, there will be no continuity for gay people to really know about our past. There may be books, sure, but it’s not so easy to find the personal stories. Partially that’s why I’m doing what I’m doing.

Your new project follows that thought pattern.

Definitely. I’m interviewing older gay men – men over 70 and 75 – because I want to get the stories on how it was like for them. To navigate the experience of being gay in the 1940’s and ‘50’s. It’s not so much about who they are now, but I want to hear about their personal journey in a time when it was all completely illegal and stigmatized and there was obviously no community to connect with. I’m not sure how the project is going to end up. It may wind up as an internet project with maybe 10 or 30 documentaries, each about an individual person and very entertaining, nicely edited and put together. Like freestanding character studies. And I would like them to be available for young people, forever, to know what it was like before Stonewall. Because it was a completely different world back then.

Do you personally have the feeling that you have to contribute?

I do feel that I have to contribute. It’s the thing that drives me in life. Maybe it’s because of my Jewish background, but I am someone who feels driven by idealism. The form in which that contribution manifests is not very specific but because I somewhat became a public figure; I’m trying to utilize my reputation to give myself a public voice, to be an activist. Both We Were Here and The Cockettes are love letters to San Francisco. And even though We Were Here is very emotionally loaded, it’s still an inspiring film about the beauty of a community coming together. I’m not the kind of person that stays home and complains about how awful things are, I want to speak to people to be more creative, to be loving, be more compassionate so that everybody’s desire to contribute can be constructively supported.

What would you say to a 15 year old gay person, reading this article?

That it’s becoming easier, fortunately. Not for everyone, because certainly in small towns and in religious families it can just be as difficult to be queer as it was for someone in the 1940’s. But at least people have access to the internet now and realize that they are not the only one, which makes a huge difference. Last night I was talking to a young man who told me he would run to the theatre as soon as my new project about gay elders was finished. I suggested that he could also have a REAL conversation with an older person, ask to hear their story. People are carrying enormous amounts of history inside them and love to tell their stories so I always encourage people to try to broaden their horizons. Whether it’s through reading books or going on the internet, but just learn about other cultures and what older people have lived through, what people in other societies lived through, look what goes on for gay people in Saudi Arabia or Iran. Curiosity is the most beautiful thing you can cultivate. Always be curious, never be afraid to ask questions and try to follow your heart.

www.davidweissmanfilms.com

www.cockettes.com

www.wewereherefilm.com

Related articles

Bernard Perlin

The Cockettes

As the psychedelic San Francisco of the ’60’s began evolving into the gay San Francisco of the ’70’s, The Cockettes, a flamboyant ensemble of hippies decked themselves out in gender-bending drag and tons of glitter for a series of legendary midnight…..

Our Hands On Each Other

Our Hands On Each Other is a multi-disciplinary artwork by New York based artist and historian Leah DeVun. A project consisting of photographs, performances and conversations centered around queer and feminist space. To document rural…..

Billy, the world’s first out and proud gay doll

To celebrate and document their conceptual artwork Billy, also known as Billy – The World’s First Out and Proud Gay Doll, artists John McKitterick and Juan Andres have launched a new website. In the highly politically and emotionally charged atmosphere…..

April Ashley

Born in Liverpool in 1935, April Ashley, a former Vogue model and actress was one of the first people in the world to undergo pioneering gender reassignment surgery. As one of the most famous transgender individuals and a tireless campaigner for…..

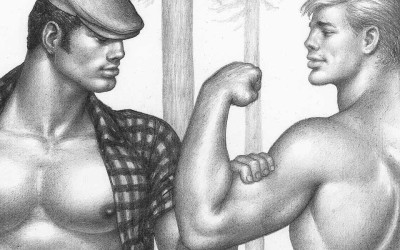

Bob Mizer & Tom of Finland

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) presents Bob Mizer & Tom of Finland, the first American museum exhibition devoted to the art of Bob Mizer (1922–1992) and Touko Laaksonen, aka ‘Tom of Finland’ (1920–1991), two of…..

New Club Kids

The Noughties saw the rise of a new generation of Club Kids following in the footsteps of their predecessors – the original Club Kids of New York City, who, in turn, had followed London’s Blitz generation. In the early 1980’s, the Blitz Club in London’s…..