Geen Resultaten Gevonden

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text & photos Courtesy of National museums Liverpool

Born in Liverpool in 1935, April Ashley, a former Vogue model and actress was one of the first people in the world to undergo pioneering gender reassignment surgery. As one of the most famous transgender individuals and a tireless campaigner for transgender equality, she is an icon and inspiration to many. For the first time, the Museum of Liverpool explores April’s very public story through her previously unseen private archive and investigate the wider impact of changing social and legal conditions for all trans and lesbian, gay and bisexual people from 1935 to today.

Childhood

April Ashley was born George Jamieson, one of six children to Frederick, who served in the Royal Navy, and Ada, a factory worker. The family’s poor living conditions meant they were soon moved by Liverpool Corporation from Pitt Street, in the Chinatown area, to Norris Green. Although born a boy, April always felt and looked like a girl. Childhood was a lonely and very confusing time. At St Teresa’s primary school she was bullied for being different. As a teenager April did not grow facial hair, her voice refused to break and she began to develop breasts.

Identity

Aged 15, April joined the Merchant Navy as ‘I decided to face up to my situation and it seemed to be one of the things that made you a man’. Feeling and looking different in this very masculine environment, however, was very challenging. Whilst on leave in America, and seeing no way out, she attempted suicide in 1952. After recovering she was given a dishonorable discharge. Back in Liverpool, April continued to struggle alone with her gender identity and in 1953 made another attempt to take her own life by jumping into the River Mersey. She was sent to Ormskirk Hospital psychiatric unit and later treated at Walton Hospital. Her care was brutal and included sodium pentothal injections and electro convulsive treatment followed by a course of male hormones. The experiences were devastating and had a detrimental effect on April’s health and well being. In 1955, aged 20, April decided to leave Liverpool for London. In London April worked at a Lyons Corner House, a bustling cafe and informal, underground meeting point for artists, bohemians and gay men. Being gay or trans was a precarious and illegal life. Homosexuality was not decriminalized until 1967 and trans and gay people faced much discrimination. Being in London gave April anonymity and the freedom to accept and reveal her true identity. In this supportive environment and with other trans role models around her, she began to call herself ‘Toni’ and wear female clothes and make-up. It was here in 1956 that she made an invaluable connection that was to take her to Paris and the world famous Carrousel club.

Le Carrousel

Le Carrousel de Paris was renowned for its spectacular performances by male and female impersonators, which attracted stars such as Ginger Rogers, Claudette Colbert, Marlene Dietrich and Rex Harrison. In stark contrast to post-war England, Paris represented a sexual liberalism, freedom and openness that was previously unimaginable to young April. She was soon employed at the club and paid £12 per week. Assuming a new identity and using the theatrical name of ‘Toni April’, she performed alongside famous female impersonators, Coccinelle, Bambi and Peki d’Oslo. Her confidante and closest friend Bambi introduced her to a Parisian doctor who prescribed the female hormone estrogen which further assisted April’s feminization. April was soon touring with Le Carrousel across Europe. Whilst in Milan she visited the British Consulate to attempt to change the name on her passport from George Jamieson to ‘Toni April’ but was met with hostility. Throughout her life April had recognized that she wasn’t a boy and knew that she could not be ‘cured’ through therapy, medication or psychiatry. She longed to become the woman she felt she had always been. Working at Le Carrousel she had saved enough money to attempt to make this wish come true. Her friend Coccinelle suggested she contact Dr George Burou, a pioneer in gender re-assignment surgery who was based in Casablanca, Morocco. She left for Casablanca on 12 May 1960 and within three days of arriving the correction of her genitalia from male to female was complete. She was the ninth patient on which Dr Burou had performed the surgery. It was a complex but successful operation. As a consequence her hair fell out and she endured significant pain, but April had finally become the woman she had always believed she was. She told Dr Burou that it was ‘the happiest day of my life’.

High profile career

Following gender reassignment surgery in 1960 April returned to London and changed her name to ‘April Ashley’ by deed poll. With her statuesque good looks and newfound confidence she became a fashion model and actress. She was photographed for high profile publications such as Vogue and socialized with famous musicians, actors and members of London’s high society. In 1961 April met and began an affair with Arthur Corbett, an Eton-educated aristocrat. Corbett had frequented Le Carrousel and was fully aware of April’s history and gender re-assignment. Corbett left his wife and four children to begin a relationship with April.

Outing

On Sunday November 19th, 1961 April Ashley was outed as a transsexual in the Sunday People newspaper, prompting numerous other headlines around the world. The press coverage of April’s gender transition was hostile and transphobic, portraying her in an inhuman way. April was humiliated and shocked by the unexpected revelations. Her modeling assignments soon stopped.

Marriage

In 1963 April married Arthur Corbett in Gibraltar, but the relationship soon broke down and April returned to London. Corbett petitioned for divorce in 1967 using the grounds that April was born male and therefore the marriage was illegal. The medical and legal position on transsexuality was divided, no consensus on whether a person could legally change gender could be reached and it was left to the divorce court to decide. This proved to be a test case, which continues to have implications for people throughout the world today.

Corbett vs Corbett

In February 1970 the case of Corbett vs Corbett was heard and became universally known as the divorce case which set a legal precedent regarding the status of transsexuals in the whole country. The judge Lord Justice Ormrod, created a medical ‘test’ and definition to determine the legal status of April, and by extension, all transsexual people. This was a huge personal setback to April, who suffered intrusive tests and more derogatory press attention. The judge ruled in February 1971 that ‘she was male’ and the marriage was annulled. This ruling became a legal precedent used to define the gender of transsexual people for decades. The legal status of transgender people has only been fully recognized since the introduction of the Gender Recognition Act 2004. In the 1990s and early 2000s April continued her campaign to have her true gender recognized. She lobbied and wrote to Prime Minister Tony Blair and the Lord Chancellor, remaining resolutely committed to changing the law for all transgender people. In 2005, after the passage of the Gender Recognition Act 2004, April was finally legally recognized as female and issued with a new birth certificate. The then Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott, who had previously worked with April in the 1950s, helped her with the procedure. In 2012 she was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for services to transgender equality and continues to be an inspiration to many today.

A collaborative project between the Museum of Liverpool and Homotopia – the international festival of queer arts and culture. This exhibition is supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund. It was a key part of Homotopia’s 10th anniversary in 2013.

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text & photos Courtesy of MOCA

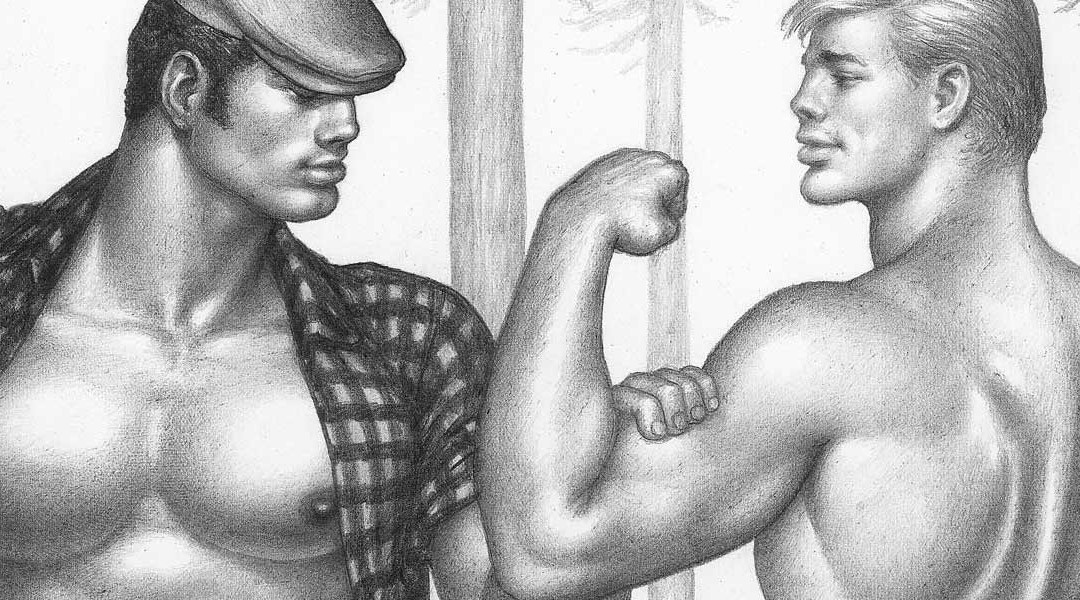

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) presents Bob Mizer & Tom of Finland, the first American museum exhibition devoted to the art of Bob Mizer (1922–1992) and Touko Laaksonen, aka ‘Tom of Finland’ (1920–1991), two of the most significant figures of twentieth century erotic art and forefathers of an emergent post-war gay culture.

The exhibition features a selection of Tom of Finland’s masterful drawings and collages, alongside Mizer’s rarely seen photo-collage “catalogue boards” and films, as well as a comprehensive collection of his groundbreaking magazine Physique Pictorial, where drawings by Tom were first published in 1957. Organized by MOCA Curator Bennett Simpson and guest co-curator Richard Hawkins, the exhibition is presented with the full collaboration of the Bob Mizer Foundation, El Cerrito, and the Tom of Finland Foundation, Los Angeles.

Tom of Finland is the creator of some of the most iconic and readily recognizable imagery of post-war gay culture. He produced thousands of images beginning in the 1940s, robbing straight homophobic culture of its most virile and masculine archetypes (bikers, hoodlums, lumberjacks, cops, cowboys, and sailors) and recasting them—through deft skill and fantastic imagination—as unapologetic, self-aware, and boastfully proud enthusiasts of gay sex. His most innovative achievement though, worked out in fastidious renderings of gear, props, settings, and power relations inherent therein, was to create the depictions that would eventually become the foundation of an emerging gay leather culture. Tom imagined the leather scene by drawing it; real men were inspired by it … and suited themselves up.

Bob Mizer began photographing as early as 1942, but unlike many of his contemporaries in the subculture of illicit physique nudes, Mizer took the Hollywood star-system approach and founded the Athletic Model Guild in 1945, a film and photo studio specializing in handsome natural-bodied (as opposed to exclusively muscle-bound, the norm of the day) boy-next-door talent. In his myriad satirical prison dramas, sci-fi flix, domesticated bachelor scenarios and elegantly captivating studio sessions, Mizer photographed and filmed over 10,000 models at a rough estimate of 60 photos a day, seven days a week for almost 50 years. Mizer always presented a fresh-faced and free, unashamed and gregarious, totally natural and light-hearted approach to male nudity and intimate physical contact between men. For these groundbreaking perspectives in eroticized representation alone, Mizer ranks with Alfred Kinsey at the forefront of the sexual revolution.

Though Laaksonen did not start spending time in Los Angeles until the early 1980s, he had long known of Mizer and the photographer’s work through Physique Pictorial, the house publication and sales tool for Athletic Model Guild. It was to this magazine that the artist first sent his drawings and it was Mizer, finding the artworks remarkable and seeking to promote them on the magazine’s cover, but finding the artist’s Finnish name too difficult for his clientele, who is responsible for the now famous ‘Tom of Finland’ pseudonym.

By the time the gay liberation movement swept through the United States in the late 1960s, both Tom of Finland and Bob Mizer were already well-known and widely celebrated as veritable pioneers of gay art. Decades before Stonewall Inn and the raid on the Black Cat Tavern these evocative and lusty representations of masculine desire and joyful, eager sex between men proliferated and were disseminated worldwide at a time when the closet was still very much the norm—there was no such thing as a gay community. If these artists were not ahead of their time, they might just have foreseen and even invented a time.

Spanning five decades, the exhibition seeks a wider appreciation for Tom of Finland and Bob Mizer’s work, considering their aesthetic influence on generations of artists, both gay and straight, among them, Kenneth Anger, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, David Hockney, G.B. Jones, Mike Kelley, Robert Mapplethorpe, Henrik Olesen, Jack Pierson, John Waters, and Andy Warhol. The exhibition also acknowledges the profound cultural and social impact both artists have made, especially in providing open, powerful imagery for a community of desires at a time when it was still very much criminal. Presenting the broader historical context and key aspects of their shared interests and working relationship, as well as more in-depth solo rooms dedicated to each artist, the exhibition establishes the art historical importance of the staggering work of these legendary figures.

In addition to approximately 75 finished and preparatory drawings by Tom of Finland spanning 1947– 1991, the exhibition includes a selection of Tom’s never before exhibited scrapbook collages, and examples of his serialized graphic novels, including the legendary leatherman Kake, as well as a selection of Mizer’s ‘catalogue boards,’ AMG films, and a complete set of Physique Pictorial magazine. An accompanying publication includes texts by the exhibition co-curators and a selection of images.

The Museum Of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Check the MOCA website on related programs and more info.

All the images are printed with permission of MOCA Museum Of Contemporary Art.

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

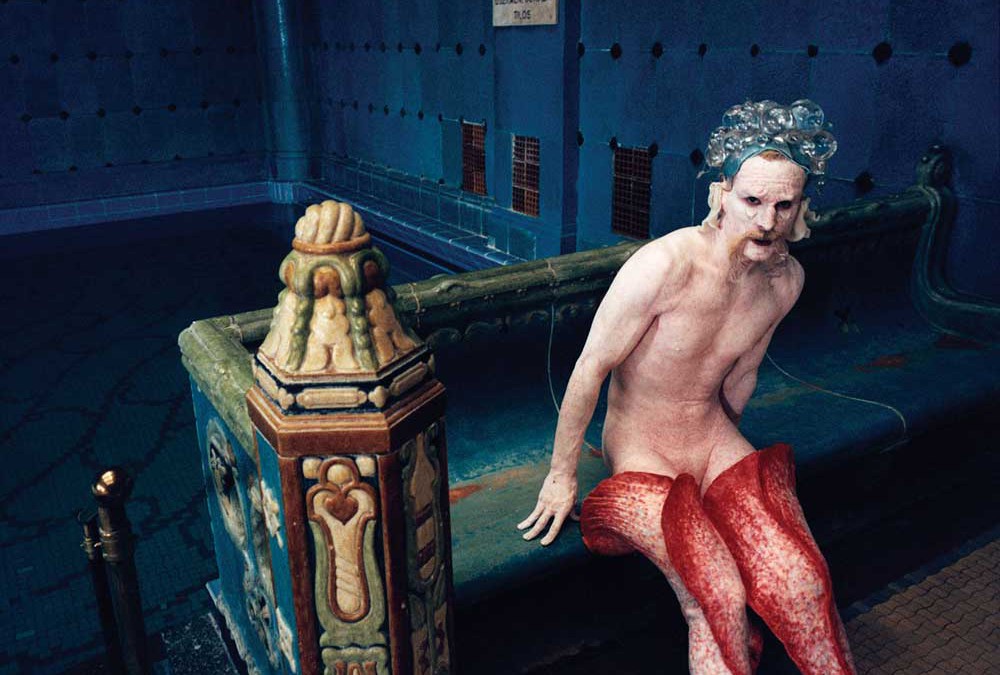

Text JF. Pierets Photos Michael James O’Brien

When talking to some friends in Antwerp, the name Michael James O’Brien was often mentioned. One couple bought a series of his pictures, another met him in a bar in Antwerp. When searching his name online, one can only produce a shriek of recognition. That picture of fetish legend/corsetiere Mr. Pearl! Dame Edna covered in pink feathers! Our über idol Matthew Barney! Iconic pictures that we’ve known for years turned out to be by the hand of an accomplished American photographer and poet who has exceeded in the field by being showcased in the greatest publications around such as Rolling Stone, L’Uomo Vogue, the New York Times, the Financial Times and many more. Michael James O’Brien. We managed to get his email address and were able to intercept him on his way to Istanbul.

When did you knew you wanted to be a photographer and why?

I was seduced by Walker Evans (and his groundbreaking work) when I took his graduate seminar at Yale in the early 70’s. I bought a Pentax 6×7 & changed my degree from literature to photography.

You come from Ohio and travel the world, yet you are often in Antwerp.

I taught in Ohio for 2 years only but was born in NYC & lived there after Yale until I moved with my partner to Paris in 2004. Now we move around constantly.

Among other things you owned a restaurant, your work has been commissioned by a long list of magazines and you are a published poet. Do you need to do all those things in order to feel fulfilled or are you easily bored?

I like to be busy and do big projects. Writing & photography & owning a bar are all inspiring & satisfying in different ways.

You photograph celebrities as well as dragqueens and performers. You like to be divers in your subjects?

I am attracted to a wide variety of subjects like most photographers. I don’t have one subject matter or a set style.

What’s your most treasured anecdote?

What comes immediately to mind is a walk with Ursula Andress through the Opera House in Budapest in 1996 preparing shots for Matthew Barney’s Cremaster5 when Ursula began to tell me about her “great loves”. You’ll have to imagine the rest…

You worked with Matthew Barney. How did that happen?

I worked with Matthew when he was a model while he was still in college in the late 80’s. When he began his art exhibitions in NY we often met in what were once called “underground” venues, like the fetish club Jackie 60 & Matthew asked me to collaborate on Drawing Restraint 7.

The people on your pictures often look fragile. Is that something you are looking for?

I am trying to give room & time when I do portraits for the subject to find their resting place. It becomes more difficult these days with instant photography to make the time.

When did you decide to make ‘Girlfriend: men, women and drag’?

I proposed the project to Random House in 1990 at the height of the Golden Age of NYC downtown nightlife which was often dominated by drag performers.

You seem intrigued by transformation. Why is that?

I am deeply interested in what is called the gender diaspora, in all it’s manifestations & I believe we all have the power to become what we want to be in spite of the “givens” of birth, race etc.

I read you have a fascination for freedom versus restriction. Is that a personal thing?

It’s equally personal, political & aesthetic but those are inseparable for me.

You do a lot on the subject of AIDS. Why?

I was in NYC when the epidemic hit like a tsunami. Loss was an essential part of our lives as in a war and the only response was awareness, involvement.

What’s next on your agenda?

Exhibitions in Istanbul in June & in October and preparation for shows in London & Liverpool, as well as commissioned work. And open a bar!

What’s the most important thing on your wishlist?

To work with less pressure; to re-edit my archive!

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

Text JF. Pierets Photos Rudy Thewis

Jonathan Kemp won two awards and was shortlisted twice for his debut London Triptych. Gay bookstore Het Verschil in Antwerp, asked to interview the British author for a live audience due to the Dutch translation of his novel, Olie op doek. A conversation about history, gay writers and a fascination for language and sex.

In London Triptych you tell three stories. There’s the rent boy Jack Rose in the London of the 1890s, of the 1950’s with painter Colin Read and male escort David, living in the London of the 1990s. The three stories explore the subculture and underworld of male prostitution. You seem to know quite a lot about the subject matter?

I did a lot of research in one way or another, and I was very interested in giving a voice to the voiceless. Male prostitution is a minority within the society of prostitution. Most of the historical focus has always been on female prostitution so they’re like a minority within a minority. As a writer you’re always trying to find a perspective that has not been tackled before and this seemed like a really interesting angle.

London Triptych started out as a short story called ‘Pornocracy’, which told the tale of Jack Rose, one of the boys who testified against Oscar Wilde in 1895. Is Jack historically correct?

Jack starts to work as a telegram boy and then he got involved in prostitution through this man called Alfred Taylor. Taylor really existed and supplied boys to Wilde so there are elements of truth from what I had gathered on research. If it weren’t for the fact that Wilde had been arrested and in prison, it would be even harder to find material on the subject matter. Ironically, given the negative outcome for Wilde, that kind of stamped it in the history books in a way that it wouldn’t have been otherwise. The transcripts of the trial have been very useful. Jack himself is an invention. He’s a mixture of a lot of different boys Wilde played with – he called them Panthers. Their danger appealed to him, their lack of gentility. He was a well-educated, upper middle class man so he liked their roughness, this spontaneity that he didn’t find in his immediate circle.

You seem like a big Wilde fan.

I have loved Oscar Wilde ever since I was a teenager. As I got older and came out myself, I got more interested in gay history. Wilde almost became this figurehead. The idea that he established in many ways, the parameters, the identity that was to go on in the 20th century. The concept that he is almost the prototype of the modern homosexual. He gives it a shape, a voice and a way of being. That was always fascinating to me. I often think the work is overshadowed by his life but I find him an incredible wordsmith. The poetry and ideas in his books have always appealed to me.

Your love of Wilde, the fact that London Triptych is populated by rent boys, models, aristocrats, artists and gangsters,… are you a little nostalgic?

I must say that Jack became my favorite character, that was my favorite piece to write, What appealed to Wilde in these boys is what appealed to me when I got under Jack’s skin. There must have been many Jacks in London at that time and the more I read about queer history, the more I became interested in trying to represent that minority voice.

The minority voice stays but times are changing.

Jack could go to prison for what he was doing, but David, the male escort in the 1990s, is free because of the change in the law in 1967. It’s sort of a history of gay liberation and the humanitarian progress during the century.

The book is filled with sex but it remains sexy instead of becoming a dirty story. It’s a thin line between what your write and pornography.

I’m fascinated by the way that language expresses human experience. Pornography is the most straight forward way sex can be represented. It has a very specific aim and that is to turn you on. There’s nothing wrong with that but it felt a bit limiting to me. I’ve always been attracted to writers like Jean Genet, who wrote about sex in a much more poetic way. For me it was essential to the book that sex had to appear but not in a sort of bashful way. The most interesting thing is often ‘what goes where and who does what to whom’, so I wanted to find much more different metaphors and to describe the emotions rather than the mechanics.

When I read the book if felt like all 3 characters were imprisoned. Because of love. Is that so or is it just my imagination?

As much as sex was an important aspect, love was also. When it became clear to me that this was going to be a novel about prostitution, I wanted to write three love stories. Love coming from the least likely places for example. They are very tragic love stories and I wanted to overturn the cliché of the hard-bitten prostitute who is incapable of love. So love and that trajectory of love is very important.

You ran a theatre company in the 90’s. Why did you switch from that to writing novels?

Writing theater plays was actually a diversion from writing prose. I have always written novels. The first one I wrote was when I was about 17. But I didn’t really pursue it very hard. Every writer gets rejected by publishers but when I got the letters I gave up quite quickly, thinking it was no good. At that time I was living with an actor who wanted to do his own plays so I thought ‘how hard can it be?’ We started of with monologues, it was a one-man show, and after a while I added more characters and got more confident with each play we did. When the company disbanded because there wasn’t enough money in theatre – even less than in books – I went back to writing prose. So London Triptych was the first novel I wrote after the excursion into the theatre.

Your second book is called Twentysix. It’s not a novel nor is it a collection of short stories. I wrote down: ‘Poems about sexual encounters between men. One of every letter of the alphabet’. It’s completely different from London Triptych

It is, but I think it picks up on some of the themes of London Triptych. When I was writing about London and its sexuality, I was trying to gain some originality or poetry in the descriptions. I wrote Twentysix almost immediately after the novel was finished. At first I just wrote down these short episodes, these short encounters. I was exploring language and post structuralism, reading Derrida, Bataille, and wanted to experiment. Midway through the book I considered what to do because I could go on writing about these sexual encounters and publish this huge volume, so I had to put a limit to that. 26 seemed like a slim manageable number.

I read on the net that you once said; ‘I think sometimes being gay has led me to broader horizons than it otherwise would be.’

I think straight comes with a script. You are aware of the life trajectory you’re expected to follow. The model you’re expected to conform to. You’re going to get married, have children, a mortgage. I’m not saying that all people do – and I know straight people who forge a different path – but I think that, when you don’t have that script at hand, you create new possibilities. You kind of invent a way of being. And there is a sort of courage that comes from having to live outside that mainstream model. There’s a security in that model that is not available to you.

It’s a different way of being in the world. You have to be more original in the things you are going to be or going to do. Just that slightly greater edge of invention.In London Triptych, David describes playing a game when he was a child, standing on a train track, with all his friends. The game was called ‘chicken’ and was about who could stand there the longest. David always won. This unanticipated courage, that was me. I knew from the beginning that staying where I grew up would kill me. Spiritually.

Being gay is as much about character as having a sexual drive?

Whether moving to London had to do with my sexuality, I don’t know, maybe that was a force of character that made me invent and explore. I do think it had to do with the sexual exploration and with courage, I find it hard to separate the two.

Some gay writers don’t want to be referred to as being ‘a gay writer’. Because they are also a white writer, a male or female writer, an American writer,… Yet you don’t mind being in that category.

I don’t. You can call me a black writer if you want to. I can understand why people are against it but then I think; ‘you are gay and you write, so why not’. I feel that it can work negatively because maybe straight readers wouldn’t go for a gay book. While gay readers will rush to it, but nevertheless will also read lots of straight books. So I understand why that label can feel restricted but I don’t mind. I love to write for gay people. It matters to represent these lives in books. People identify with what they read so why not write for gays. I can imagine that some straight people might find a book like Twentysix quite alien but then again, parts of their lives are alien to me. I’m not trying to write for everyone, I’m trying to write for people who can find something in my work. If a straight reader has an open mind, well go ahead. When I came out, exploring my own sexuality, I discovered there was a whole history of gay men writing. That was great! To know that now, after centuries, you have bookshops filled with gay writers is just fantastic. Its history is very short compared with the history of literature, but to discover people like Genet, Vidal or Capote who were exploring and experimenting was a revelation. By putting a label on it, it allows gay readers to find those books. Because if you are confronted with this huge mountain of literature as a gay man or a gay woman, you are going to want to find the books that speak to you because we are all looking for books that give us alternatives. The alternative to see the world from a different consciousness. So I think if you are looking for gay books and there is a big sign where to look, I don’t mind. I find it very useful. It saves you a lot of time. It’s all about things you want to share.

You are not afraid to exclude readers?

Those kind of closed minds are not the kind of people you want to speak to anyway. I can’t say that I’m never going to read a book by a straight person because they have nothing to say to me. Then you will be missing out so much of the things I’ve read and enjoyed.

You are working on a third book.

Yes, and it’s almost finished. My first two books are very related because I was fascinated about sex and language. My new novel is something completely different. The main character in All There Is + All There Is Not, is a 65 year old woman who lives on a narrowboat in North West London. One day she’s out shopping and she sees the spitting image of her first husband who died 40 years previously. She thinks she’s going mad. She keeps on seeing him and it turns out that he’s not a ghost, not a figment of her imagination but a gay man with a striking resemblance, like people often do. He becomes a portal to her. And like Alice she’s tumbling through a portal to an entirely different life and culture.

Sounds great! Looking forward already.

And last but not least. What’s your most flamboyant future dream?

I would love London Triptych to be made into a TV series. A British 3-part TV drama.

And if you were asked to play one of the characters? Who would you choose?

Oscar, of course.

www.myriadeditions.com/jonathankemp

www.birkbeck.academia.edu/jonathankemp

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.

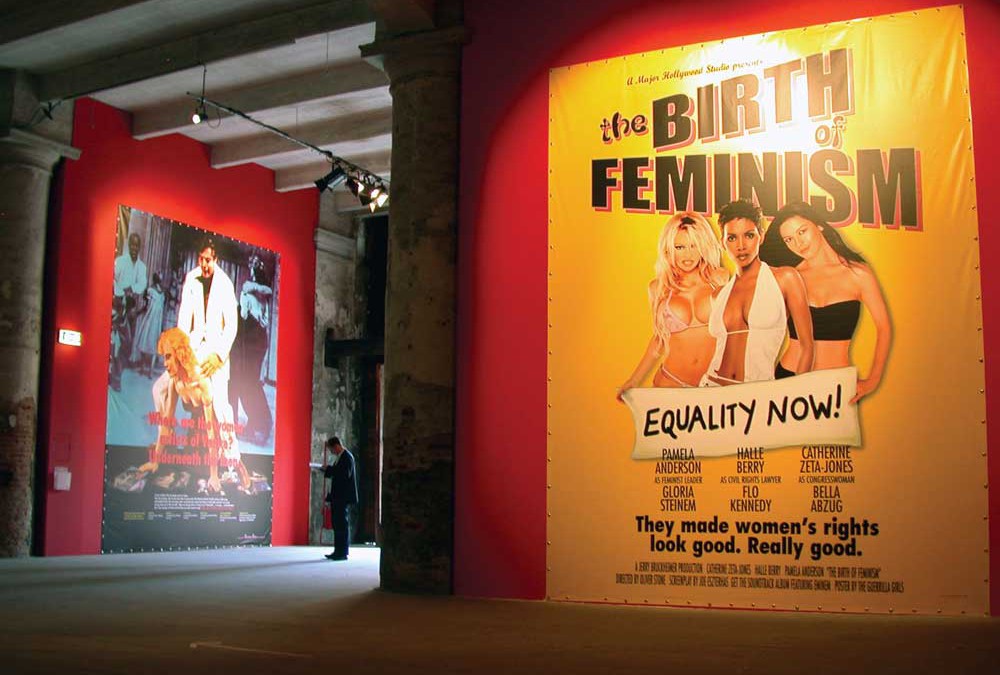

Text Wendy Donckers Photos Courtesy of The Guerrilla Girls

The Guerrilla Girls are a group of anonymous estrogen-bomb dropping, creativily complaining feminists. They fight discrimination and corruption in politics, art, film and pop culture with ‘facts, humor and fake fur’. Behind their scary gorilla masks you can find women of all sorts and kinds with pseudonyms of dead female artists. Let’s take a look at the Guerrilla Girls’ deadly weapons.

Facts.

The Guerrilla Girls started off in 1985, after a protest against an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the most influential museum of modern art in the world. The exhibition included only 17 women out of the 165 displayed artists. A bunch of female artists made posters that stated these facts of discrimination and put them up throughout art neighbourhood SoHo. The Guerrilla Girls were born. The group started making statistics of women artists and artists of color in museums, academies and art galeries. They committed themselves to counting, writing letters, and researching museums and galleries. “There’s a popular misconception that the world of High Art is ahead of mass culture. But everything in our research shows that, instead of being avant garde, it’s derriere.”, the Guerrilla Girls stated in an interview on their website. The GG’s even did a ‘weenie count’ in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. They came to the conclusion that less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections were women, while 85% of the nudes were female. A new Guerrilla poster was made and showed the back of a naked gorilla-headed woman that lies down and seems to say: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” A quarter of a century later the same updated poster demonstrates figures that have hardly changed: female artists at the Metropolitan Museum dropped down to 4% and the female nudes became 76%.

Many other posters came up, as well as stickers, a website and fun fact books. The GG’s hung up female named banners over the generally male artist names on European museum façades, invaded the Venice Biennale with giant banners, launched a anti-film industry billboards in Hollywood right before the Oscar Awards, put up an interactive feminist banner outside the city art gallery at the Art Boom festival at Krakow and many more. With their striking statements and provocative appearances the Guerrilla Girls continuously endeavour to undermine the reigning stereotypes in the art world and other areas. “One poster led to another, and we have done more than hundred examining different aspects of sexism and racism in our culture at large, not just the art world.” In their campaigns the ‘girls’ don’t avoid other sensitive subject that are important to them such as abortion rights, the gulf war, racism, queer issues, homelessness and (sexual) violence. “We are a collaborative group, we don’t work in an orchestrated way. Members bring issues and ideas to the group and we try to shape them into effective posters.” 28 years after the start the Guerrilla Girls have become a habitual -and sometimes notorious- presence in exhibitions, film festivals, newspapers, university aula’s, museum bathrooms and on walls and billboards all over the world. “What started out as a lark has become an ongoing responsibility, a mission. We just can’t abandon our masked duty! It’s been a lot of fun, too!”

Humor.

Another main mission of the Guerrilla Girls is to modernize the word ‘feminism’, their own proclaimed ‘f’ word. Although they call themselves ‘girls’ and sometimes wear short skirts and high heels, the Guerrilla Girls consider themselves pure feminists. “By reclaiming the word ‘girl’, it can’t be used against us. Wearing those clothes with a gorilla mask confounds the stereotype of female sexiness.”, one of the members confirms drily. With their –let’s say- remarkable appearance the GG’s hope to shock and provoke the world. “Our situation as women and artists of color in the art world was so pathetic, all we could do was make fun of it. It felt so good to ridicule and belittle a system that excluded us.”

To the question of how many the Guerrilla Girls are, their answer is that they secretly suspect that all women are born Guerrilla Girls. “It’s just a question of helping them discover it. For sure, thousands; probably, hundreds of thousands; maybe, millions.” Over the years the Guerrilla Girls have become one fluid and crazy but close family off all ages, As they work anonymously they hardly ever accept new members. They rather stimulate their numerous fans all over the world to take them as a roll model and start up their own actions and strategies. And most of all motivate them to complain, complain and complain, but rather in a funny and creative way. To give an idea, they published their Guerrilla Girls’ Art Museum Activity Book, wich is stuffed with funny games, facts and tips like ‘putting up posters and statements in the museum bathrooms’ and ‘dress up and give a do-it-yourself guided tour in your favorite art gallery about the real story behind the displayed art.’ The Guerrilla Girls’ website has several downloadable posters and stickers, like for example the call to drop a new weapon on Washington: the Estrogen Bomb. ‘If dropped on the super-rich trying to take over the country, they would throw down their big guns, hug each other and start to work on human rights.’

Fake fur.

Shortly after their first actions in 1985 and the following press attention, the group members decided to hide their identities when appearing in public. As most of the members are active in the small art world, they prefer to avoid career problems and to bring the focus to the issues, not to the Guerrilla Girls’ personalities. And it seems to help: the mystery surrounding their identities has attracted attention ever since then.The GG’s give themselves names of dead female artists like Frida Kahlo, Eva Hesse, Kathe Kollwitz, Gertrude Stein and Georgia O’Keeffe, in order to reinforce these women’s position in cultural history.The slightly aggressive gorilla masks with sharp teeth were an accidental idea that emerged after a bad speller wrote ‘Gorilla’ instead of ‘Guerrilla.’ The masks immediately became symbol of the Guerrilla Girls’ strength. The good avengers are not afraid to use their loud voice or roll their muscles. But at the end the day, each Guerrilla Girl hangs up her mask and returns anonymously to her daily life. Untill the next mission comes along. And looking at the world today, these kind of missions will still be required for a while. So if you see some Gorilla heads popping up behind the corner of your street, don’t get scared and run away. Just join and play.

De pagina die u zocht kon niet gevonden worden. Probeer uw zoekopdracht te verfijnen of gebruik de bovenstaande navigatie om deze post te vinden.